By Daniel Snowman, Senior Fellow, IHR

This is the final in a series of three blog pieces by IHR Senior Fellow, Daniel Snowman, raising provocative issues about how we regard and memorialise what we think of as ‘history’. Read the first and second blogs here and here.

I was born in London the year before the War broke out, and learned as a child that I was living through ”history”. My father helped put out the fires as the city was ”blitzkrieged” and he was later an anti-aircraft gunner on the coast. My mother took me into the garden to watch our chaps flying out on their bombing missions and then, in the evening, returning with a sad gap or two in their formations. I sat next to her as she listened to the news on the wireless, rejoiced when we heard of the death of Hitler, and danced around the street bonfire on what I learned to call ”VE Night”. As Churchill growled his uplifting messages over “the BBC”, everyone knew that history was being made.

History, or what we regard as ‘history’, keeps shifting with the passage of time, reinterpreted through the perspectives of the ever-changing present. Thus, the Japanese have been re-writing school history books (particularly the sections about the Second World War), and I recall being told that they were doing something of the same in Ukraine and Poland as they attempted to distance themselves from Russia. Did the British empire help educate millions around the world into the benefits of democracy or was it, as many have increasingly insisted, primarily a form of ruthless (and racist) commercial exploitation? How do you currently regard—and label—the mass murder of Armenian Turks over a century ago? In Israel, intellectual life has been much exercised in recent years over new interpretations of the evacuation (expulsion?) of Arabs from Palestine in 1947/8.

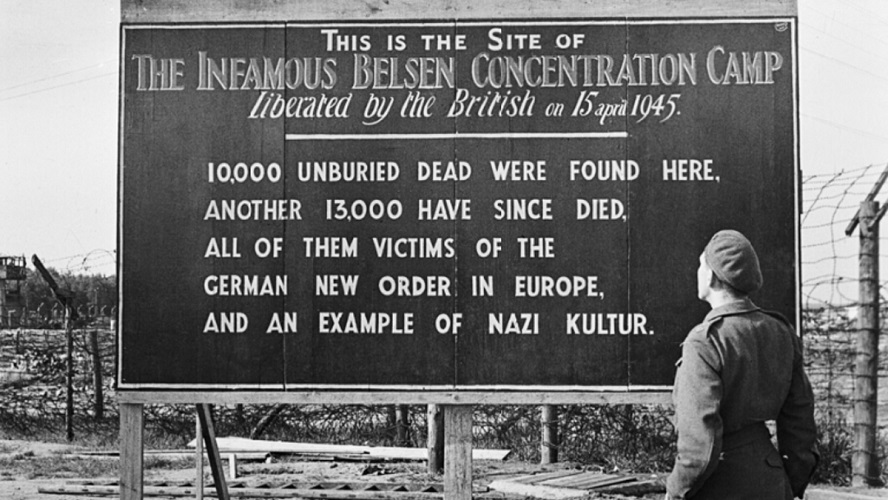

If these examples are contentious, consider the questions raised by a site such as Auschwitz and nearby Birkenau. Auschwitz is a monument, a museum, and a memorial, as well as being a ”site of historical interest”. As a museum, it has to cater for large visitor numbers and this means providing such mundane facilities as car and coach parks, conference rooms, cafeterias, toilets, and retail outlets.

Many come to Auschwitz in a spirit of pilgrimage, perhaps to mourn the loss of parents or grandparents and to seek out information about their fate. But the neat streets and buildings they see on entering the camp, and the carefully displayed and labelled exhibits, can create an almost sanitised view of what once went on here. Buildings and barbed wire have, after all, required periodic renovation after exposure to decades of freezing Polish winters and, to that extent, are no longer ”original”. Some visitors do not at first realise that the mass murder occurred not here but a couple of kilometres away at Birkenau: a huge, empty, often windswept open-air site now containing little more than a few huts and a railway line—in its sheer bleakness, all the more appalling to anyone with an ounce of imagination. All this raises profound questions about the relationship between present and past. Is there an element of conflict between the maintenance of Auschwitz-Birkenau as monument, museum, and a memorial? And is there (as some have suggested) a touch of almost ghoulish voyeurism in the growing popularity of what has come to be known as ‘’dark tourism”?

Some forty-odd years ago I was visiting Munich for the BBC and set off one morning for the nearby suburb of Dachau, site of one of the earliest Nazi concentration camps, and by then a museum and memorial. While I was there a group of young German soldiers arrived for an educational visit and, after an initial briefing, they were invited to ask questions and express their views. ‘I understand the importance of retaining the memory of the dreadful things the Nazis did,’ said one earnest young man in his late teens. ‘But the result is that we, who had nothing to do with the crimes they committed, continue to be labelled by the outside world almost as though we did.’ He had a point, everybody agreed. But wasn’t it right that places like Dachau (not to mention a mass murder camp like Auschwitz) should be preserved? Well, yes of course, someone else said. But why are we so selective about what we do and don’t choose to memorialise from Germany’s Nazi past? ‘Here in Munich we have made a museum out of Dachau. But there is no plaque marking the Beer Hall where Hitler staged his notorious 1923 putsch.’ Not, he hastened to add, to celebrate it; merely to mark it as a location of historical significance. Fair enough, piped up another young soldier. ‘But if there were a plaque outside the Beer Hall—or the house in which Hitler lived when in Munich—the danger is that the neo-Nazis might leave flowers at these places and turn them into political shrines.’ The debate, much of which I recorded, was vigorous, and I found it moving to see and hear the honest integrity with which this younger generation of Germans struggled to come to terms with the barbarous legacy of their recent predecessors.

I didn’t leave Dachau to return to my hotel in Munich until well into the afternoon. I suddenly realised how hungry and thirsty I was, having had nothing to eat or drink since early morning. Somehow, the minor and temporary discomfort I felt seemed deeply appropriate. As I thought back over the day I had just experienced, I decided not to break my fast until dinner time that evening.

I have often wondered, looking back, whether there might there be a case, if only out of deference to the dead, for leaving the site of a Nazi concentration camp to disappear with the passage of time. Or even to build over it, perhaps creating a memorial park in the hope of creating a better world hereafter? I don’t pretend to have easy answers to disturbing questions such as these. And I have been shaken to the core when contemplating them during visits to Auschwitz over the years, deeply conscious that the War and Holocaust occurred during my own lifetime, not so long ago. I pray that Auschwitz never becomes just another stop on the tourist trail.

But time is passing. When I began work some 25 years ago on my study of the cultural impact of the ”Hitler Emigrés”, many of the most famous of them—the refugee writers, musicians, architects, film-makers, historians, publishers, and the rest—were still alive and prepared to let me record lengthy interviews with them (many now in the sound archives of the Imperial War Museum).

Today, most of those I interviewed have passed on as the entire story moves out of “memory” and gradually becomes “history”. Most scholars studying the War nowadays have no personal memory of it; rather, it is coming to be regarded as a subject requiring cool and balanced research, like the study of, say, the Napoleonic wars.

This is right and proper and not to be demeaned. I would not argue that everyone has to become a highly sophisticated quasi-professional historian. But a proper awareness of the passage of history is surely among the more important skills any responsible person should strive to acquire.

For ‘history’ is a blanket term for all that has preceded—and can therefore help to throw light on—everything in the present. Nothing comes of nothing (as King Lear almost said), and one cannot understand the world of today without knowing what led things to be the way they are. I am reminded of the wise words of the great French historian Marc Bloch (who was executed by the Nazis in 1944):

“Misunderstanding of the present is the inevitable consequence of ignorance of the past.”

Daniel Snowman is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Historical Research, University of London.