This is the first in a series of three blog pieces by IHR Senior Fellow, Daniel Snowman, raising provocative issues about how we regard and memorialise what we think of as ‘history’. These will be published monthly.

We all seek what we think of as ‘historical authenticity’. In which case, suggests Daniel Snowman, shouldn’t the famous Tower of Pisa be restored to its original perpendicular form? Or allowed to collapse with the passage of time? The one thing that isn’t historically authentic, surely, is to use modern technology to retain its (otherwise temporary) leaning position.

Italy is crammed with historic works of art in need of restoration. Like the figures on a rotating weather vane, one great building or gallery pops out for all to see just as another goes into hiding for a while. In the 1990s, as tourists in the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel marvelled at the renewed brightness of Michelangelo’s ceiling, visitors to Pisa were in for a let-down. The Leaning Tower, which all came to see and perhaps had hoped to climb, was out of bounds, encased in scaffolding—with copious explanations about how here, in the Piazza dei Miracoli, the latest miracles of modern science would finally freeze the tower’s historic tilt. The issue was not so much the restoration of a fading or eroding work of art dating from long ago. If the proposed solutions here in Pisa were new, the problem was not.

The origins of the tower go back to the 12th century, when Pisa’s city fathers decided to celebrate the power and spiritual authority of their state with the erection of a superb marble cathedral and baptistery, topped off by a great campanile or bell tower. An adjacent cemetery, the marble-encased Camposanto, would complete the project. Here would be a sanctified spot of incomparable beauty where all the rites of passage—baptism, marriage, death, and burial—would be guaranteed appropriate care, each heralded by the pealing of bells from Pisa’s great campanile.

Things didn’t quite work out that way. The cathedral, baptistery, and subsequently the Camposanto were completed as planned. But not the cylindrical tower. Soon after it began to take shape, it started to tilt. Those responsible for its construction came to realise not only that the alluvial terrain on which it and the adjacent buildings rested was soft and unstable, but that that the great, hollow weight of the emerging tower rendered it particularly prone to buckling and possible collapse. Work was repeatedly suspended as successive generations of engineers tried to work out whether it was possible to stabilise their precarious structure; indeed, whether the bell-tower would be viable at all. For well over a century, it had no belfry (and therefore no function) and altogether it took nearly 200 years before the entire building was completed. By now, the late 14th century, Pisa had suffered a succession of military, political, and economic downturns, rendering it far from the proud and powerful city state its great Piazza had originally been intended to celebrate. Thus, the great campanile, conceived in an era of triumph, was finally born into one of acute anxiety. The painful but precise symbolism of Pisa’s increasingly tilting tower was not lost on people at the time.

From that day to this, the big question has been how to render the Leaning Tower as safe and stable as possible. Of course, if safety were the only concern, the best thing to have done at various stages in Pisa’s history would have been to demolish the tower, or perhaps to rope off the entire area and leave the tower to collapse in its own good time—thus becoming an authentic historic ruin, not unlike much of the Roman Forum. Another kind of historical authenticity might have been achieved if efforts had been made to re-straighten the tower, thereby rendering it as close as possible to the perpendicular structure originally planned. Some have argued that the tower should simply be anchored more deeply, encased and corseted, or held in position by a series of stakes, guy ropes, and wires in a state of permanently enclosed suspense. Suggestions have ranged from the highly practical to the unimaginably bizarre. The only ones to have been seriously entertained have been those aimed at maintaining and stabilising the historic tower, as it is and where it is*, tilt and all, so that future generations could continue to experience a remarkable inheritance from the past. But how?

* When Venice’s historic opera house, La Fenice, was burned down in 1996, all agreed it should be rebuilt “com’era, dov’era”: as it was, where it was.

The issue was never simply one of engineering; security concerns jostled with religious, aesthetic, and financial considerations. And, all the while, the intertwining of myth and history added a patina of inviolability to Pisa’s flawed masterpiece. Pisans grew to love their leaning tower, its all too evident disablement providing an integral part of its attraction—not only for Pisans, indeed, but to visitors from across Europe and the wider world. Like the Pyramids or the Sphinx, the tower attracted an accretion of legends as an old boat gathers barnacles. From its earliest years, its tilt was popularly attributed to various malign forces: a nefarious builder wreaking revenge on the city fathers for his poor wages, or one or other of Pisa’s traditional enemies—the Genoese, Florentines or Saracens. Perhaps it was God’s punishment against the Pisans for their vanity and presumption, just as he had punished the builders of the Tower of Babel. Or, par contra, maybe the fact that the tower didn’t actually fall was a sign of divine grace and beneficence. The mythmaking did not stop there. Galileo is said to have climbed the tower in around 1590 with two cannon balls (or stones) of different weights and dropped them simultaneously in order to prove his point that the velocity of a falling object is unrelated to its mass.

Over the next couple of centuries, as travel opportunities expanded, word of Pisa’s freakish tower spread among young men embarking upon the Grand Tour. To Shelley and his friends (including Byron and Leigh Hunt) Pisa came to be something of a headquarters, the city—especially its stooping tower—endowed with rich, romantic associations normally reserved for the ruined residues of ancient Greece and Rome. By the later 19th century, the Tower of Pisa was firmly on the international tourist trail, a Mecca for lovers of art and history—and a favoured last stop for lovers of a different kind: the rejected, scorned, and star-crossed, set on suicide.

Throughout much of its history, few seem to have believed the tower would actually fall. It had, after all, survived since early Renaissance times and, for long periods, its angle of tilt had scarcely shifted. Then, in 1902, a spectacular event forced everyone to think again: the venerable campanile of St Mark’s, Venice, developed a fissure and collapsed. One of the most famous landmarks in Italy, revered by generations of visitors, was no more (it was later reconstructed a safe distance from the church). If this could happen in Venice, where the fallen building had been sound and upright, but merely old, something similar could surely occur in Pisa. More commissions were set up, a whole string of them by Mussolini in the 1920s and early 1930s; measurements were taken, wind speeds monitored, earth drained, holes drilled, cement injected, ballast added, soil extracted and counterweights installed on the side opposite the lean—and still the Tower tilted, permanently and self-evidently close to catastrophe.

Soon, the tower faced a novel risk. As Allied forces pressed their way up the Italian peninsula in 1944, some historic treasures were inevitably damaged or destroyed. At Montecassino, where German troops were believed to be holed up, the Allies decided there was no alternative but to bombard the great Benedictine monastery. The Pisan Piazza dei Miraculi was soon faced with the possibility of a similar fate. In the event, the Tower was reprieved (though the Camposanto and the priceless art works it contained were firebombed, while much of the town south of the Arno was severely damaged).

After the war, Pisa’s tower soon regained its status as one of the most familiar buildings in the world, comparable in fame and instant recognisability to the Pyramids, the Taj Mahal, and the Eiffel Tower. Then, in 1989 in Pavia, north of Pisa, a late medieval bell tower suddenly collapsed, killing four bystanders. The shockwaves emanating from Pavia were felt most intensely in Pisa and, in January 1990, the Leaning Tower was closed to the public and a new commission appointed. Many Pisans, denied their city’s most marketable product, watched with understandable cynicism as the latest experts tackled the city’s oldest problem. Their cynicism grew when, in 1995, the tower suddenly lurched even closer to collapse, partly in response (it seemed) to the alleviative measures being taken. A year later the commission was dismissed. But a year after that, in 1997, an earthquake wrought huge destruction to another of Italy’s most revered locations, Assisi. Hastily, the Pisa commission was reconvened. The Leaning Tower of Pisa simply had to be saved—and quickly.

A new chapter was added to the 800-year-old story when, in 2001, eleven years after the tower was closed and after the expenditure of $25 million, it was finally pronounced safe and reopened the public. Once again, tourists thronged to Pisa and were permitted to ascend the 290-odd stairs of the tilting tower—in parties of no more than 30 at a time. The restoration work apparently pulled the tower’s inclination back from the brink of collapse by 44 centimetres, but it didn’t feel like it as visitors climbed their way gingerly up the ancient spiral staircase. It was not unlike climbing up from deck to deck aboard a ship in rough seas—except that the Pisa tower offered no railings or ropes to hold onto. This was not a walk for the weary, the faint of heart, or those prone to vertigo. Atop the belfry, for those who had managed this giddy summit, was a lookout post that protruded some four-and-a-half feet beyond the base of the tower: a crazy crow’s nest caught severely off-centre in a storm-tossed yet frozen ocean. From here, if your stomach could take it, was a wonderful view of the cathedral and the surrounding city and countryside. A few moments of calm and you were off again on the similarly vertiginous descent—probably having to move aside to make way for another party on their way up. Nowhere else did the idea of walking ‘in the footsteps of history’ resonate quite so meaningfully.

Why have people flocked to the Leaning Tower of Pisa? The city is replete with history. It contains a famous university, is the birthplace of Galileo, and houses many historic and religious buildings, among them a church along the banks of the Arno whose treasures include a reliquary supposedly containing a thorn from the True Cross. The handsome Piazza dei Cavalieri boasts a palace that was richly embellished by Vasari in the 16th century for the Medici family and turned by Napoleon into a university college in the early 19th. But it is to the Piazza dei Miraculi that every visitor has turned, a monumental testimony to an earlier, rich, confident age. Most visitors enter the superb cathedral and baptistery, savouring the work of Nicola and Giovanni Pisano, and the adjacent museums packed with artistic and historic treasures. But above all, of course, they come to the Leaning Tower. The tower, as we have seen, brings together an unusually wide range of concerns: historical, spiritual, aesthetic, financial, political, and scientific.

Deeper psychological imperatives seem to be involved, too. Risk and danger clearly have their enticements. Just as part of the attraction of bungee-jumping or white-water rafting or watching a bullfight, Formula One race, or high-wire act is the unspoken awareness that the worst might occur but probably won’t, the irresistible point about the Leaning Tower of Pisa is the thought that it (or you) might just possibly fall. Nobody would bother about the white-knuckle rides at fairgrounds if all sense of danger were removed. In much the same way, Pisa’s tower would lose its special appeal if straightened. Italy is full of medieval and Renaissance towers you can climb. But none is as famous as Pisa’s, for there is something deeply unnerving about a tower that is leaning so precariously, an unnerving yet ultimately reassuring sense of natural law successfully defied.

What Pisa offers is a kind of freak show. This is what people come to see, to be photographed against, to climb. This is the image the souvenir stalls sell in their superabundance: Leaning Tower books, aprons and ashtrays, tilting coffee mugs and postcards. But look a little closer and another souvenir, just this side of decency, keeps recurring: little models of naked women embracing phallic-looking leaning towers. It would seem that, for some, in addition to its many other enticements, Pisa’s celebrated erection does more than merely tilt or lean.

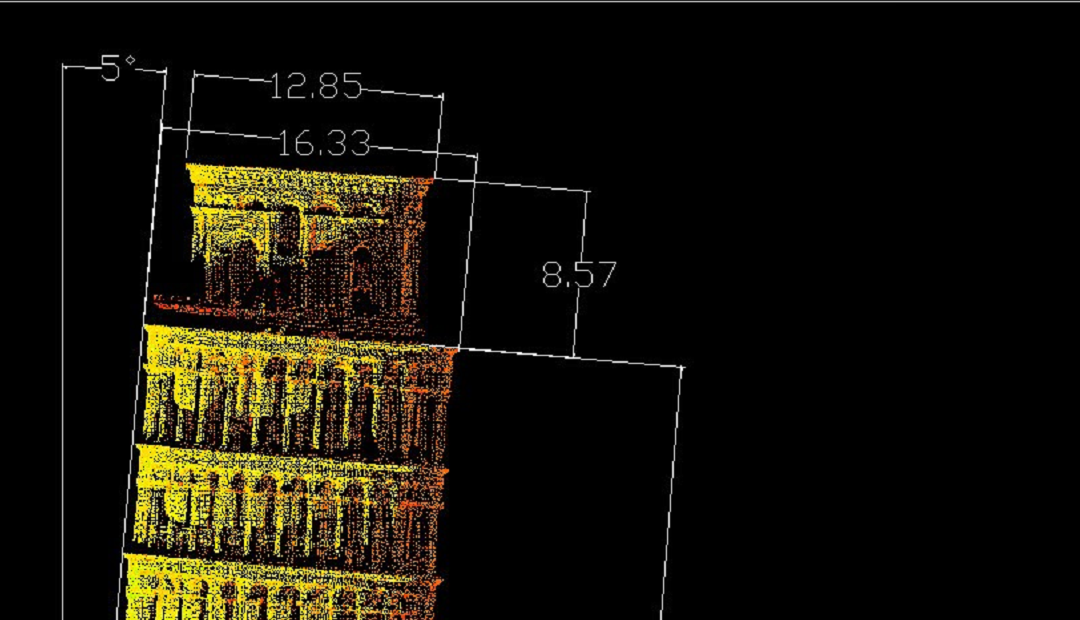

Banner image: An elevation image of the Leaning Tower of Pisa cut with laser scan data from a University of Ferrara / CyArk research partnership, with source image accurate down to 5 mm (3⁄16 in).