By Janette Bright

In 2020, as the world around us changed dramatically, IHR students (past and present) decided that as their contribution to the IHR Centenary celebrations they would look back at their predecessors from the very beginnings of the Institute. This last instalment in our series of blogs reflecting on the student experience over the last 100 years will consider continuity and change at the IHR, looking at some of the training courses provided both for post-graduate students undertaking further degrees and students who attended on an occasional basis. The main source for this research is the series of IHR annual reports, an almost complete run of which is held in the Wohl Library of the Institute. It has been interesting to consider how when we started this project in 2020, we were just entering a world of disruption and challenge. In contrast the students of 1921 were moving away from their own period of trauma. Of course, they had had to deal not just with a pandemic but the impact of global warfare too.

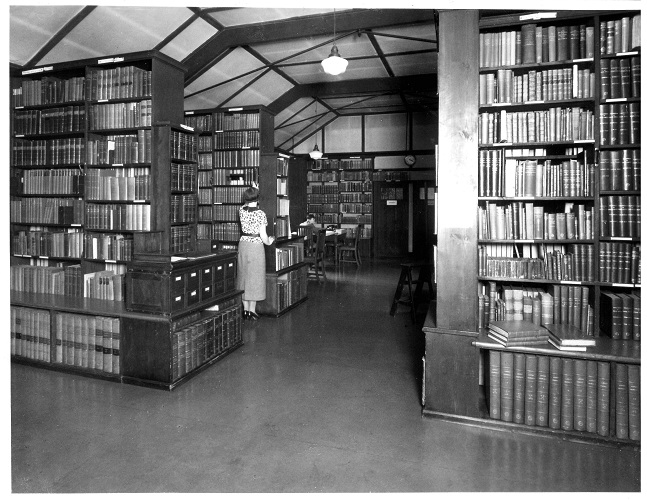

Those first students in the 1920s may have felt optimistic with the promise of a new historical laboratory to enhance their studies after the events of the 1910s. The specialist research training offered by the IHR during the 1920s and 1930s included several courses looking at primary sources, from the 13th to the 19th centuries, mainly related to English and colonial studies and with course titles that varied little over the period. In 1927-28 there was an additional course on the history of British India, but it does not appear to have been repeated. Studies of palaeography were offered from the very beginning. These concentrated on Latin texts but extended to include Dutch (1925-29) and Greek (1926-27). For a few years (1935-39), there was also An Introduction to the History of Western Handwriting, which included practical sessions on reading historical texts.

As the world entered a further period of conflict in 1939, no doubt many of the students who had begun their studies had to change their plans. However, the training planned for the academic year 1939-40 suggests that there was an expectation that some students would continue. Alongside courses relating to specific legal, economic, bibliographic, and newspaper sources (all new that year), there were two lectures on Work on Records, with Special Reference to War-Time Conditions.[1] It would be fascinating to know the content of these. Even with this preparation one wonders how, and even if, any students managed any research over the next few years. How many continued to study (or even survived), has not been explored in this current research project—something for future historians to consider, perhaps. The IHR had closed temporarily from 1940, although initially there was some limited access to the library, and unsurprisingly courses did not resume until 1945. Once hostilities ended the Institute began to return to normal, at least in terms of restarting its training programmes.

In the academic year 1945-46 the Institute began with just two traditional courses. They were An Introduction to the Sources of English History from the 6th to 12th centuries, alongside An Introduction to Palaeography and Criticism. Course content continued to focus on sources of English history for specific chronological periods throughout the 1940s; occasionally more specialist topics were also offered. These included, in 1947-48, an introduction to medieval manuscript illumination. Although this was only available for one year initially, it returned as an introductory course in 1953, and then continued until 1965. A course on the History of Islam in the Near East ran only during the year 1948-49, whereas An Introduction to the Sources of Byzantine History fared much better, lasting from 1948-49 until 1953. In 1961-62 several courses (each lasting just one academic year) considered the social implications of technological change in the Commonwealth, international history (1815-1939), and the diplomatic background of the Second World War. A specific course looking at methods and sources for women’s history did not appear until 2002-03, despite it becoming an area of historical interest from the 1970s.

In 1987-88 a partly residential course, sponsored by the Economic and Social Research Council, concentrated on London-based sources for economic and social history. The IHR Annual Reports for 1989 and 1990 describe how these intensive courses were over-subscribed, with 56 students in the latter year. In July 1988, the IHR also experimented with a one-week summer school focused on archives and historical method, organised jointly with the Public Record Office (PRO). Though it was reported not to have been well attended in its first year, the decision was taken to repeat the course. In its second run it was described as well subscribed, with 20 students ranging from amateur historians, graduate students, teachers, and staff from the PRO.

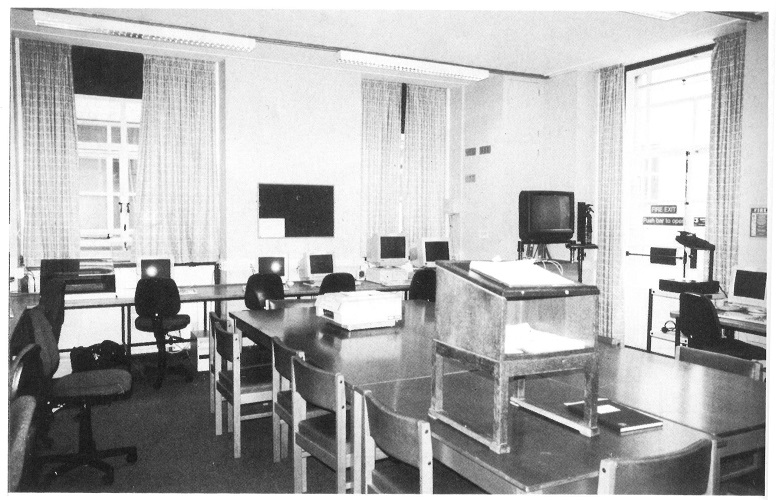

With a new decade, the IHR began to administer Master’s degrees for the University of London. The first of these seems to have been the one or two-year (full or part-time) MA in Computer Applications for History, in 1990-91. The Institute had obtained for the students’ use 12 micro-computers, which were shared with members of the university’s Computer Users Group. The course consisted of four elements. There were three taught modules, the first exploring the ways historians had used computers in their research and the techniques that had dominated. The second module provided practical computer skills, while the third allowed students a choice of options—programming, quantitative methods, or image analysis. The fourth element was a 10,000-word dissertation.[2] Though this MA was relatively short-lived (it does not appear in the list of courses offered after 1994), several short courses relating to computer use appeared regularly in the 1990s. By 1993 the Institute had a new computer suite with 20 computers, so it is not surprising that an effort was made to encourage their use. In 1993-94, Caroline Stead taught an Introduction to using electronic mail, and from 1995 there were an Internet Data Course, An Introduction to the Use of the Internet for Historical Research (from 1996), and An Introduction to Sources for Historical Research on the Internet (in 1999). Use of computers is now so ubiquitous that it is easy to forget how ground-breaking email and the internet once were. Fast forward 20 years and students are not only regular uses of such technology but can now access a wealth of material from their phones and other portable devices.

More recent courses at the IHR have reflected some of these developments in the digital age, including concepts relating to social media. In 2018 a course run by the IHR on Creating and maintaining an online presence showed historians how to build a basic website but also considered the usefulness of social media to historical work. Methodologies such as GIS (geographic information systems) have also been catered for. GIS, along with social networking techniques, allow students, and indeed established historians, to look at data about people and place in new ways. However, not all of the most recent IHR courses have required digital skills. A favourite course of mine was Visual Sources for Historians (first listed in 2002), which taught not only how to find images and analyse them, but how to consider architecture as primary source material.

IHR students now also benefit from training from the School of Advanced Study (SAS), which opened in 1995. Also, it should also be recognised that not all training is performed in classrooms. Training also comes through attendance at seminars and conferences—listening and debating with other students and academics. With the recognition of the power of public engagement to demonstrate the value of the humanities, students can also become involved with activities such as those promoted by events like the Being Human Festival, held annually since 2014.

Although the crisis of 2020 seriously impacted students’ research, there was already much in place to facilitate a continuance of studies, some of which have had a lasting legacy. Staff worked particularly hard in the first few weeks of the pandemic to provide access to as many primary and secondary sources as possible, online or by email. In addition, the university opened access to numerous resources previously hidden by pay walls. Unlike our predecessors from the class of 1939, current students may have been severely restricted in some ways, but when the buildings were closed there were many ways we could continue our studies. We have also benefitted from the assistance of bodies outside the university: some libraries and archives provided virtual reading rooms, whilst many others offered additional scanning services. Now current and future students may be able to continue to use such technologies, perhaps to assess whether a distant source is worth a physical visit. The pandemic also made more common alternative ways of communicating and connecting with other scholars—video conferencing, webinars and the like were technologies available before 2020, but which, until Covid-19 hit, had often not been fully explored. One of the main benefits of online conferencing is the ability to attend something that looks vaguely interesting but perhaps cannot be justified in terms of time and money. Perhaps you are only interested in one paper—with a virtual conference you can attend for just that. But it has also created greater access to those who might have been excluded due to mobility issues, family commitments, or financial constraints. Online conference attendance does have its drawbacks though—it is definitely not as convivial as meeting in person, particularly as it is more difficult to engage with others through a screen.

But if 21st century technology has made how and what we research very different to those of our counterparts of 100 years ago, there are still fundamental elements of historical research that have not changed. One key example is the need to analyse sources and write up a thesis. There is little doubt that earlier students had similar problems of choosing what to include and exclude, whilst acknowledging the need to write coherently. It is impossible for the students of today to imagine, as it was for those of the Jazz age 100 years ago, how study will change over the next 100 years. There are bound to be new methodologies, new ways of accessing records, new ways of communicating our ideas, as well as new topics to research. And yet there will also be the same pressures of finding time for study and writing, finding the right tone, and ensuring we are contributing something original to our chosen academic field.

Bibliography

Being Human website, (2022), online – https://beinghumanfestival.org/ [accessed: 26.6.2022]

IHR Annual Reports (IHR/6/2) – Almost complete run: reports for 2005/06; 2007/08; 2011/12 are missing. Reports for 2001/02; 2002/03.

‘M.A. in Computer Applications for History’ in Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung, 1990, Vol. 15, No. 4 (56)

School of Advanced Study website, (2022), Our History, online – https://www.sas.ac.uk/about-us/our-history [accessed: 26.6.2022]

[1] This one-off course to prepare students for war time conditions had been presented by Hilary Jenkinson of the Public Record Office and I was pleased to note that he did return to teach again in 1946. See Phil Winterbottom’s blog of May 2022, ‘What to seek, and how to find and use it’ – Students, Archives and the IHR for more biographical information on Jenkinson.

[2] ‘M.A. in Computer Applications for History’ in Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung, 1990, Vol. 15, No. 4 (56), p.201

Janette Bright first enrolled at the IHR as a Masters student, undertaking an MRes in Historical Research in 2016. After successfully graduating a year later she began a part-time PhD with the Institute. For her Master’s degree Janette looked at the education of the children of the London Foundling Hospital in the eighteenth century. For her current research she is looking at the Founding Hospital in terms of its creation and maintenance. Janette works occasionally as a Museum Assistant at the London Foundling Museum.

This blog is part of the IHR centenary project, From Jazz to Digital: exploring the student contribution at the IHR, 1921-2021.