By Phil Winterbottom, PhD student, IHR

When in 1904 Albert F. Pollard first spoke of his idea for a post-graduate school of research in history, he began by outlining why such an institution should be based in London: ‘here we have a monopoly of advantages which no other city in the whole Empire can boast’. The concentration of primary sources in the capital meant that ‘graduates who aspire to research in Modern history are compelled to resort to London. For here in the Record Office (now The National Archives), the British Museum (now the British Library), and in other Government Departments are stored the vast bulk of materials on which they must base their work’. He added ‘It is true that the Bodleian has considerable manuscript collections unused, untouched, unseen; it is true that there are archives at various noblemen’s seats, like those of Lord Salisbury at Hatfield, or those of the Duke of Portland at Welbeck, and of course the materials for local history must always be sought in various localities. But from the point of view of national history all these are a drop in the ocean of records existing in London. Of course, some of these have been printed or calendared, and thus made accessible in any respectable library’, but ‘of the extant materials for English history not one-tenth has yet been calendared or printed’. It was clear that London’s collective institutions made it the nation’s pre-eminent repository of historical material; an advantage that Pollard was keen to exploit in promoting his idea of an Institute of Historical Research.

Whilst Pollard’s choice of archival examples represents what might now be considered an unrepresentative ‘top-down’ approach to history, Pollard’s concern that students and scholars should be sufficiently equipped to use primary source material, and that a post-graduate school of history should provide ‘competent instruction in the meaning and use of original sources’ remains at the heart of the IHR’s activities today.

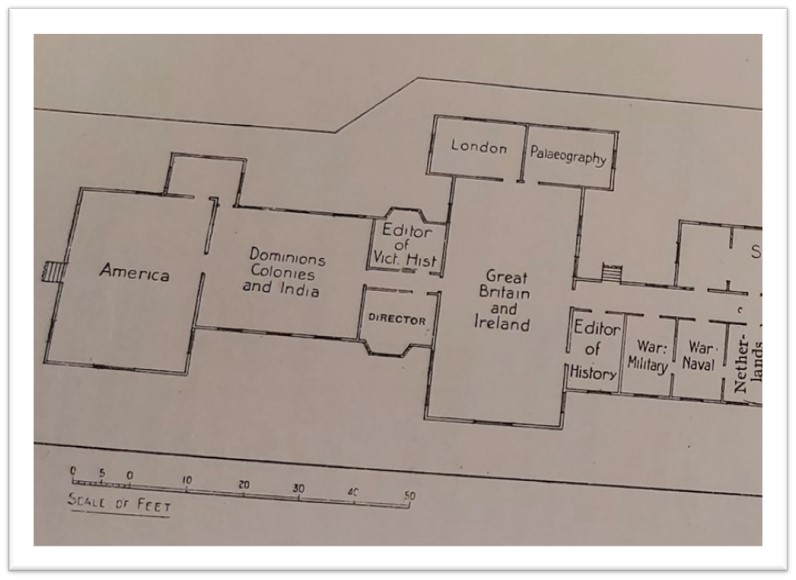

In 1919 Pollard argued for a school of history building with ‘rooms in which the materials for historical investigation can be arranged according to their subject and students trained in the methods of using them’. When Pollard’s vision was realised, in 1921, a pamphlet publicising the new Institute of Historical Research began by explaining ‘the principles on which it is based’. ‘The Institute is a laboratory in which students will be trained in the methods of historical research and in the use of archives … Its object is … to teach students what to seek, and how to find and use it, and thus to economise their labour and that of the custodians of archives. Students will pursue their actual investigations in those archives; they will come to the Institute to discuss their problems and result and to receive that oral guidance from which they are properly debarred in libraries and manuscript departments.’ The pamphlet included a description and plan of Institute’s new premises, with individual rooms containing materials on the histories of particular countries or regions.

The 1921 pamphlet concluded by stating that the IHR ‘is not a general historical library but a workshop for historical research. Its need is not for histories but for the materials out of which history is, or should be, made; and what it requires most is catalogues of MSS. and books, indexes and guides to records, bibliographies, calendars and collections of printed documents’. The Institute’s library soon held a uniquely rich collection of such material, which students could utilise as a way into the nation’s manuscript collections. In 1971 Guy Parsloe, Secretary and Librarian of the IHR between 1927 and 1943, recalled that in the library ‘the placing of the books might have seemed capricious to one as yet unaccustomed to distinguish between ‘research tools’, ‘record material’ ‘narrative sources’ and ‘secondary works’ ‘, but this arrangement reflected Pollard’s aims.

The training courses provided by the IHR were designed to help students identify, read and understand primary source material and to evaluate sources and weigh their evidence. Of particular importance was palaeography, the set of skills required to read and date archival documents. To give this ‘special treatment’ a room was dedicated to that purpose. It was to remain part of the IHR until in 1938 the Institute moved to Senate House, where the new University Library opened with its own Palaeography Room. So began the Institute’s long-standing interest and expertise in the study of palaeography.

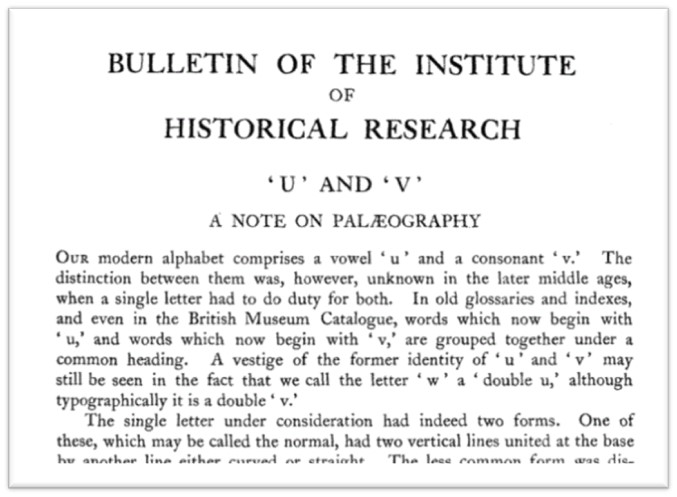

In addition to the facilities and events onsite for postgraduate students, the IHR also sought to reach a wider audience through publication of its Bulletin, which featured numerous articles relating to sources and their use written by distinguished practitioners. The first two volumes, published between 1923 and 1925, included articles entitled ‘ ‘U’ and ‘V’ – A Note on Palaeography’ (Sir Henry Maxwell Lyte, Deputy Keeper of the Public Records), ‘The Wardrobe and Household Accounts of the Sons of Edward I’ (Hilda Johnstone, Professor of History at Royal Holloway College), and ‘The Homes and Migrations of Historical MSS.’ (J P Gilson, Keeper of Manuscripts in the British Museum).

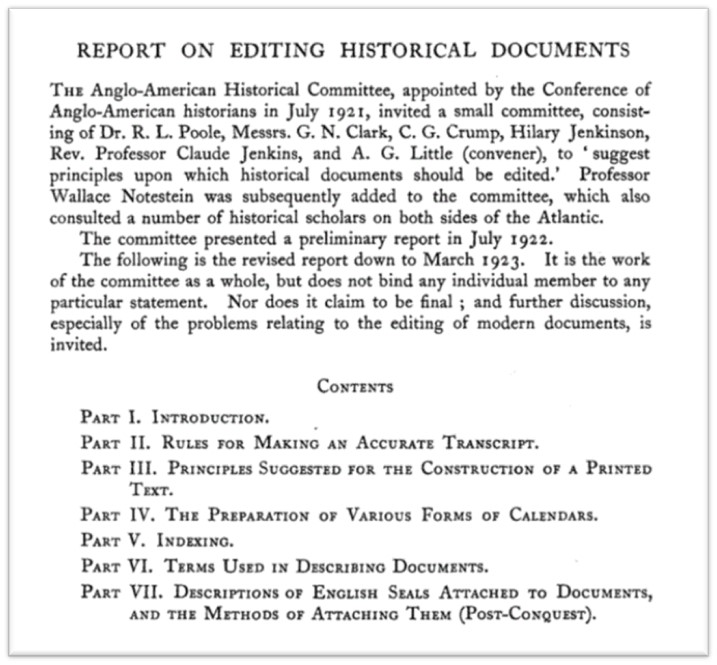

Pollard had highlighted the role of the Institute, and its interest in primary sources, alongside that of the keepers of archives. One of the joint authors of the first article to appear in the Bulletin in June 1923, a ‘Report on Editing Historical Documents’, was Hilary Jenkinson of the Public Record Office, who also for many years taught a number of the Institute’s training courses, including an elementary palaeography course for library students at UCL. Jenkinson (1882-1961) was later to serve as Deputy Keeper of Public Records, receiving a knighthood in 1949. Jenkinson’s 1922 A Manual of Archive Administration was the first textbook for British and Irish archivists, introducing elements of European archival theory. This still has iconic status for archivists, and even in 2022 continues to stimulate debate. Most archivists and many manuscript librarians were then trained on the job, but as number of archives expanded before and after the Second World War, there was a need for wider professional training. Jenkinson was responsible for the establishment in 1947 of the first archival diploma course in England, at UCL, and many trainee archivists (the author included!) would, over the succeeding decades, use the IHR’s resources as part of their studies there.

Over the century since the establishment of the Institute the archival landscape in Britain has changed enormously, initially with the pre- and post-war development of a network of county and borough archives, the establishment of the National Register of Archives in 1945, and the development of the archive profession with the foundation in 1947 of the Society of Local Archivists (now the Archives & Records Association UK & Ireland).

One of those who helped shape the new and emerging archives environment was Felix Hull (1915-2010), whose 1950 PhD thesis ‘Agriculture and Rural Society in Essex, 1560-1640’ was listed in the May 1951 issue of the IHR Bulletin. Hull was one of many mature students to have used the facilities of the IHR. He was described in an obituary by a former Keeper of the Public Records, Michael Roper, as ‘the last survivor of the heroic age of pre-war local archives, when county record offices were just being established and training took the form of learning on the job from an existing practitioner’.

After training as a teacher, Hull joined the newly established Essex County Record Office in 1938, to which he returned after the Second World War. He obtained a London extra-mural BA in history, and went on to study for his PhD at LSE, supervised by R H Tawney, whilst working as an archivist. He was appointed the first county archivist of Berkshire in 1948, and four years later became the first county archivist of Kent, where he developed a model archive service over the remainder of his career. Hull taught on the UCL diploma course founded by Jenkinson, and on similar courses at Aberystwyth, Bangor and Liverpool. A founding member of the Society of Local Archivists (renamed the Society of Archivists in 1954), he served as its vice chair and then chair. In 1979 Hull was the first local authority archivist to be elected President of the Society. He used three of his presidential addresses to reflect the contemporary relevance of Hilary Jenkinson’s work. In the last of these addresses, entitled ‘The Archivist should not be an Historian’, paraphrasing a quote from Jenkinson, he considered the potential conflicts of interest that archivists might encounter. Hull was ideally qualified to address this subject, as both an archivist and a historian, and in doing so he continued a dialogue between the two professions which Pollard and Jenkinson had encouraged.

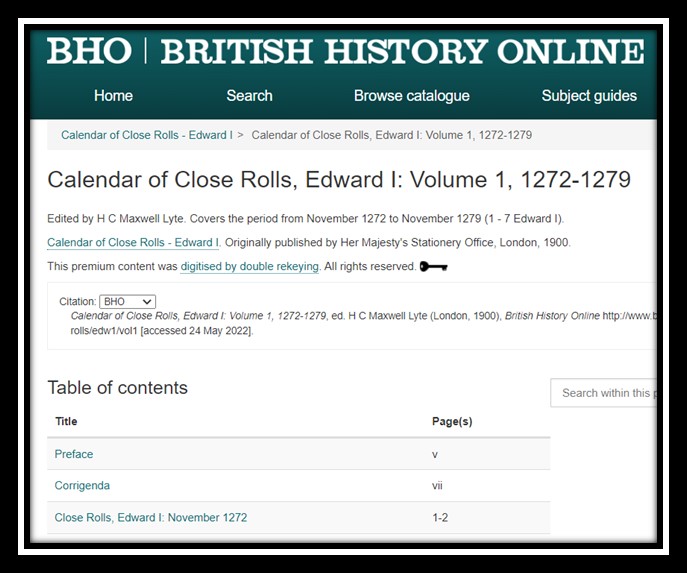

Hull’s legacy lives on in the IHR library: his guides to the Berkshire and Kent archives, catalogues of maps in the Kent and Essex archives, and A calendar of the White and Black Books of the Cinque Ports, 1432-1955 form part of the library’s core collection of catalogues and calendars of archives held in repositories spread throughout Britain.

The extent of UK archive provision continued to expand in the second half of the twentieth century with the establishment or development of archive services by universities, businesses, learned societies and other organisations, a process which has continued more recently with the growth of community archives. The introduction of online catalogues and digitised collections, and the availability of new digital research techniques has transformed historical research, as highlighted by Diane Clements in the ‘Making History’ blog in this series. The Institute adapted accordingly. As there was less need for the Bulletin to document accessions and migrations of historical manuscripts, it shifted its focus and, in 1986, was renamed Historical Research. The IHR continues to provide students with access to a unique collection of printed source material in the library, supplemented with a variety of online resources including, since the early years of the 21st century, British History Online.

The Institute’s early focus on sources and their use has remained core to its activities over the past century, and in recent years the Institute’s research training programme has included a popular ‘Methods and Sources’ week, as well as sessions focused on online research methods and digital humanities research. The latter help students navigate and interrogate the increasing number and diversity of online platforms hosting digitised sources. Since 2014 the Institute has collaborated with Senate House Library to organise the annual History Day event which brings together archivists and librarians to continue to help students and researchers know, as Pollard intended, ‘what to seek, and how to find and use it’.

Sources

Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research

‘Introductory’, Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, Vol 1, No 1 (1923), 1-5.

Birch, Debra J., and Horn, Joyce M., The History Laboratory: the Institute of Historical Research 1921-96 (London: University of London, 1996).

Gilson, J. P., ‘The Homes and Migrations of Historical MSS.’, Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, Vol.1, Issue 2 (1923), 37-44.

Hull, Felix, Guide to the Berkshire Record Office (Reading: Berkshire County Council, 1952).

Hull, Felix, Guide to the Kent County Archives Office (Maidstone: Kent County Council, 1958).

Hull, Felix, A Calendar of the White and Black Books of the Cinque Ports, 1432-1955 (London: HMSO, 1966).

Hull, Felix, Catalogue of Estate Maps, 1590-1840 in the Kent County Archives Office (Maidstone: Kent County Council, 1973).

Hull, Felix, ‘The Archivist should not be an Historian’, Journal of the Society of Archivists, Vol 6, No 5 (1980), 253-259.

Jenkinson, Hilary, A Manual of Archive Administration, including the problems of war archives and archive making (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1922).

Johnstone, Hilda, ‘The Wardrobe and Household Accounts of the Sons of Edward I’, Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, Vol 1, No 5 (1924), 37-45.

Lyte, Henry C. Maxwell, ‘ ‘U’ and ‘V’ – A Note on Palaeography’, Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, Vol 2, No 6 (1925), 63-65.

Poole, R. L., Clark, G. N., Crump, C. G., Jenkinson, H., Jenkins, C., and Little, A.G., ‘Report on the Editing of Historical Documents’, Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, Vol 1, No.1 (1923), 6-25.

Roper, Michael, ‘Obituary: Felix Hull (1915-2010)’, Journal of the Society of Archivists, Vol 32, No 1 (2011), 153-159.

Rosenthal, Joel T., ‘The First Decade of the Institute of Historical Research, University of London: The Archives of the 1920s’, Historical Reflections, 38.1 (2012), 19-42.

Steer, Francis W., and Hull, Felix, Illustrated Handbook to Exhibition of Essex Estate, County and Official Maps (held at Shire Hall, Chelmsford, 17-24 May, 1947) (Chelmsford: Essex Education Committee, 1947).

The following are among works published in 2022 which reference Jenkinson’s 1922 Manual:

Brilmyer, Gracen M., ‘Toward a Crip Provenance: Centering disability in archives through its absence’, Journal of Contemporary Archival Studies, 9.1 (2022).

Lester, Paul, Exhibiting the Archive: Space, Encounter, and Experience (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2022).

IHR archives:

IHR/6/9/1: Institute of Historical Research Prospectuses, 1928-29 to 1935-36

IHR/6/8/6-13: University of London School of History and Institute of Historical Research Instruction-Courses booklets, 1921-22 to 1928-29

IHR/6/12/4: leaflet ‘Institute of Historical Research’, 1921

Phil Winterbottom first used the IHR whilst training for a postgraduate diploma in archive studies at UCL in 1986-7. Following a career as an archivist he is now in his third year as a doctoral student at the Institute, researching personal banking in London between 1672 and 1780.

This blog is part of the IHR centenary project, From Jazz to Digital: exploring the student contribution at the IHR, 1921-2021.