By Gary Willis

Environment & History, essay no. 12

Our twelfth and penultimate contribution to our ‘Environment & History’ series by post-graduate researcher, Gary Willis, hones in on the much-contested “national interest” and its role in wartime land-management. Taking us to the British countryside before, during, and after, World War Two, Willis draws on his research to investigate how various interest groups lobbied, and policy decisions were made, about the rural environment. It alerts us to the political potency of the “national interest” as a concept, and adds some vital context to its use in times of national emergency, such as the current pandemic.

The ‘Environment & History’ series will end with Dagomar Degroot’s ‘Conflict and climate change in the Arctic: what the seventeenth century suggests about the future‘, on Wednesday 21 April 2021.

As Dr Jennifer Keating observes in Essay No.6 of this series, there is a growing historiography pertaining to the manifold impacts of war on the environment many thousands of miles beyond the battlefield. Parallel to Britain’s involvement in a number of battlefront landscapes during the Second World War, there was simultaneously another battle for land being fought across Britain in the corridors of Whitehall, by politicians, civil servants, military personnel, and representatives from civil society, all seeking to secure land for their respective aims.

In the years immediately preceding and during the war, 1,000 new military-industrial factories were built mainly on greenfield sites, to produce military hardware and materials such as aircraft and ammunition. 450 new military airfields were constructed, many involving the concreting over of agricultural land. The south and east coasts and inland areas of England became a defence zone of concrete pillboxes, anti-tank emplacements and ditches. Agricultural production was transformed from pasture to arable, two-thirds of mature woodlands were cut down for timber, and open-cast coal mining was introduced. At least seven different Government Departments across the war, the Ministries of Aircraft Production, Supply, Works, Production, Health, Agriculture, Town and Country Planning, plus the ‘Service Departments’ of the War Office, Air Ministry, and Admiralty, had a significant stake in how land was utilised for the war effort.

This demand for and acquisition of land was an extremely competitive process. In research for my PhD on the impact on the rural landscape of this war-time military-industrial infrastructure, I have been struck by the frequency with which Government departments and civil society organisations invoked “the national interest.” In documents and speeches, these bodies repeatedly used the phrase to seek a competitive advantage for their own priorities, over and above other elements of government and non-State bodies which also sought to make use of the land for war-related purposes.

The meaning of the phrase “the national interest” has a sizeable historiography all of its own, most notably J. Martin Rochester, who writes that ‘the conception of national interest revealed in state papers is an aggregation of particularities assembled like eggs in a basket…as axioms, apparently regarded as so obvious as to call for no demonstration’. [1] And more succinctly, Joseph S. Nye Jnr., who saw the national interest as ‘a slippery concept’. [2]

Fig. 1. Ministry of Information poster © British Library Board, Central Office of Information Archive, BL/PP/ Boxes 1-25, as reproduced in David Welch, Persuading the People: British Propaganda in World War II (London, 2016), p. 18.

In terms of calls on land use by the Service Departments, Britain’s Second World War began in 1937, when War Office and Air Ministry land-holdings started to increase dramatically. The scene was initially one of an uncontrolled land-grab, with the Ministry of Agriculture and civil society organisations such as the Council for the Preservation of Rural England (CPRE) and National Trust playing catch-up, trying to introduce a meaningful consultation process for the consideration of the various Government and Service Departments’ proposed land needs. In a June 1937 letter from the War Office to the Office of the Minister for Coordination of Defence, still a good two years before war became inevitable, a senior civil servant confesses that as a matter of policy it might be desirable for the War Office to agree to some sort of advisory consultation with the National Trust and CPRE, but it would have to be ‘on the definite understanding that it was subject to the right to over-ride the advice given if essential military and national interests so demand, the final decision resting with the War Office’. [3] Here the word “national” suggests that there are more interests than just military ones within the brief of the War Office, without specifying what they might be.

The Ministry of Agriculture was circumspect in how it used “the national interest” in defence of its own priorities, knowing that in a head-to-head tussle with the Service Departments over the use of land, it would always lose. In a March 1940 paper to the War Cabinet on the acquisition of land by the Service Departments, the Ministry of Agriculture conceded that it was essential, ‘in the national interest’, to give absolute priority to the Service Departments regarding the determination of the land acquisition programme. Nevertheless, it argued, there must be cases where it would be ‘in the national interest’ for the Service Departments to be content with land which was not ideal from their point of view, if this would result in preserving good agricultural land for food production purposes. [4] So here the phrase does the work of seeking to de-prioritise the needs of the military whilst avoiding setting the needs of agriculture in direct competition with it.

No sooner it seems than Britain’s new war-time factories were acting at full capacity, than attention was turning to what would happen to them once the war was over. An October 1943 Memorandum to the War Cabinet by the Minister Without Portfolio on the disposal of surplus goods and factories after the war forecast that ‘it may be desirable in the national interest that these plants should continue to run, whether for reasons of security or to secure employment and industrial development in potentially depressed areas’. [5] Speaking in the House of Commons in November 1943, the President of the Board of Trade, Hugh Dalton, announced that the Board would co-ordinate the disposal of all surplus Government factories, with ‘decisions being taken as to the best use to which these can be put in the national interest’. [6] Rural land acquired by, and built on in haste for, the Service Departments therefore had no right of return to its previous pre-war state. The industrial infrastructure located on it was now an economic asset, to be utilised in support of post-war reconstruction; for these Government departments “the national interest” was about creating employment and generating material goods for the export trade.

Fig. 2. Calgarth Factory and slipway; Photograph by Derek Hurst; Courtesy of Allan King.

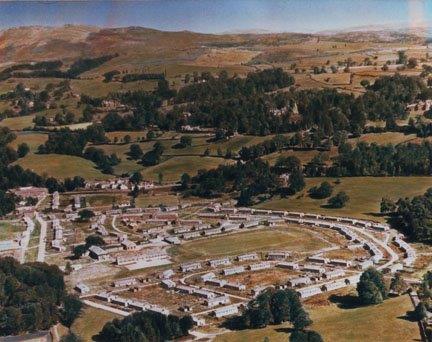

Post-war reconstruction was also of great concern to CPRE, but due to entirely different values. The organisation had carefully measured its opposition to much war-time land acquisition on the part of Government and Service Departments on the understanding that affected land would be restored after the war. Of utmost importance to CPRE was the removal of the Ministry of Aircraft Production’s Seaplane Factory at Calgarth on the shore of Lake Windermere. It had been built in 1941 in the face of opposition by CPRE and other amenity bodies, but a written promise had been extracted from the Government, consolidated by an amenity-friendly clause in the Requisitioned Land and War Works Act of 1945, to the effect that both the factory and workers’ accommodation would be removed at the end of the war. CPRE and the Friends of the Lake District viewed the removal as central to their objective of establishing a viable Lake District National Park, and their correspondence in the immediate post-war period refers repeatedly to the removal of the factory being “in the national interest.” In one particularly heated exchange with a local MP who wished the factory and accommodation to be retained in support of jobs and housing in the area, the CPRE Secretary accuses him of attempting: ‘to conceal the National Interests as distinct from the purely local interests’. [7] A national amenity interest therefore trumped merely local interests concerned with jobs and housing, and uppercase lettering is used to emphasise the point.

Fig. 3. Aerial view of the Calgarth housing estate; Courtesy of Lorna Pogson.

Ultimately, CPRE prevailed, and the factory was removed, but it was an exceptional case.

Only a few miles away stood the Royal Ordnance Factory at Drigg, on the Cumberland Coast. In June 1947 civil servants from several Government departments and the same amenity organisations met to discuss the post-war fate of the site. The representative from the Ministry of Supply acknowledged that the arguments against the site remaining on amenity grounds ‘might be very real and even unanswerable, but it had to be decided which was the more important in the true national interest’. [8] Here therefore, the Ministry of Supply infers that the promotion of a site’s amenity value may well be genuine but that the Ministry is the holder of the ‘true’ national interest, therefore trumping a mere ‘national interest.’ The ‘true national interest’ won out and led to the Drigg site becoming Britain’s largest nuclear waste dump.

What’s striking about the use of ‘the national interest’ across all of the primary sources that I have interrogated, is that in CPRE’s case, all of the references were in correspondence within the organisation, with its ally The Friends of the Lake District, and in the case of the letter I quote from, from the CPRE’s Secretary to W. M. F. Vane MP, it was marked ‘Private and Personal.’ The organisation does not appear to have used the phrase in public communications, whereas in contrast, government references are made in Parliament and semi-public gatherings, as well as in government papers and correspondence.

A difference in communication culture between different types of organisation is one possible explanation – that different arms of the State are generally much more comfortable deploying usage of “the national interest” than civil society. Certainly a significant feature of the historiography on “the natural interest” is the extent to which the phrase is utilised by various elements within State apparatus, particularly with regard to commerce. Another reason is perhaps that the association of agricultural productivity and the amenity value of rural landscapes with “the national interest” was (and perhaps still is) relatively new. Speaking at a conference of Rural Land Utilisation Officers in May 1943, the Minister for Agriculture, R. S. Hudson, cited the Town and Country Planning Act of 1932 as the first legislative manifestation of the concept that ‘the land of this country was not limited in extent, and therefore ought to be used to the best national interest’. [9] That is to say, how land could best be used could have a broader definition than previously understood. Further, whilst Professor Paul Readman credits the Victorian-era social activist Octavia Hill with imbuing future amenity and heritage values with ‘national interest’ status, [10] I suggest that a critical mass of amenity organisations did not exist until the 1920s to promote this mind-set.

But I hesitate to advocate that environmental campaigners should start to imbue their arguments with “the national interest.” I suggest that it is a phrase more significant for what its usage seeks to achieve than what it actually means. In my research context, whether deployed by a Government department, the military or amenity organisations, it seeks to elevate the importance of the user’s argument and status over and above that of other stakeholders, and to promote their view as a self-evident truth, therefore avoiding the necessity for justifying their position. It seeks to suppress dialogue rather than facilitate it, because after all nobody is against “the national interest,” or wishes to be perceived as being.

A search of Hansard Online in the present day shows that “the national interest” has not gone away. The phrase was used in the House of Commons 244 times between 1 March 2020 and mid-March 2021, [11] and it certainly demonstrates great versatility, being used across debates covering Official Development Assistance, Taxation, Innovation and New Technologies, Air Traffic Management, Poverty Reduction, and the Future Relationship with the EU. Mindful of comparisons between wartime and the current national pandemic emergency, “the national interest” also crops up 31 times in COVID debates, and has been used seven times by the Minister of Health, Matt Hancock.

Perhaps the very use of the phrase should come with a historiographic health warning.

Featured/Title Image: THE HOME FRONT IN BRITAIN 1939-1945 (TR 116) The War Effort: Dredge corn, a mixture of oats and barley used for stock feeding, being harvested. The harvest is taking place on ‘derelict lands’ put under cultivation by the Devon War Agricultural Executive Committee at Ralph Hoare’s farm at Staverton, Devon. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205188246.

References

- J. Martin Rochester, ‘“The ‘National Interest” and Contemporary World Politics’, The Review of Politics, 40: 1 (June 1978), p. 77.

- Joseph S. Nye Jr., ‘Redefining the National Interest’, Foreign Affairs, 78: 4, (July-Aug 1999), p. 22.

- Letter from the War Office to H. H. Sellar, Private Secretary in the Office of the Minister for Coordination of Defence, 24/6/37 (TNA, CAB 21/662).

- Memorandum by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (TNA, CAB 67-5; W.P. (G.) (40) 90, 29/3/1940).

- Memorandum by the Minister Without Portfolio, (TNA, CAB 66-41; W.P. (43) 437; 6/10/1943).

- Hugh Dalton, President, Board of Trade, Surplus Government Stores (Disposal), House of Commons Debate, 25/7/1944, Hansard Online (accessed 15/3/2021).

- ‘Private and Personal’ letter from H. G. Griffin, CPRE Secretary to W. M. F. Vane MP, 19/3/1949, (Cumbria Archive Centre, Carlisle, DSO/15/32).

- Notes of Meeting at Ministry of Town and Country Planning, 27/6/47, (Museum of English Rural Life, SR CPRE C/1/38/3 Drigg).

- First Conference of Rural Land Utilisation Officers, 13-14 May 1943, (TNA, MAF 48/483 First Rural Land Utilisation Officers Conference May 1943).

- Readman, ‘Octavia Hill and the English Landscape’, pp. 163-184, in E. Baigent, B. Cowell (Ed.), Octavia Hill, Social Activism and the Remaking of British Society, (Institute of Historical Research, 2017), p. 179.

- Hansard Online, accessed 13/3/2021.

***

Gary Willis is a final year postgraduate PhD researcher, in the Department of History and a member of the Centre for Environmental Humanities at the University of Bristol. His MRes dissertation (IHR, 2015-17), was developed into ‘‘An Arena of Glorious Work’: The Protection of the Rural Landscape Against the Demands of Britain’s Second World War Effort’, published in Rural History in Sept. 2018.