By Dagomar Degroot

Environment & History, essay no. 13

In the final article of our ‘Environment & History’ series, Professor Dagomar Degroot looks to early modern climate change to ask whether arctic warming necessarily results in violent conflict. Considering the effects of the Little Ice Age on seventeenth-century whaling, Degroot’s research demonstrates the importance of being precise about how climate change impacts different industries and national interests.

Highlighting past responses to less profound climate change than we are seeing today, his work suggests our current focus on negative potential outcomes might be blinding us to the unintended consequences of preparing for violent competition, and to the myriad ways climate change can affect conflict.

This is the final essay in the Environment & History series, available here in full.

The remnants of whalers’ ovens on the coast of Svalbard, July 2019. Photo by Bathsheba Demuth, Brown University.

In summer 1613, English sailors marooned a crew of Dutch whalers on the desolate coast of Svalbard, halfway between Norway and the North Pole. Without their ship, the whalers had little hope of turning a profit – or of getting home before the deadly Arctic winter. Desperate, they set out in the perpetual gloaming of one Arctic summer’s night to hunt a unicorn that some whalers had sighted nearby. They discovered something even more enticing: an English whaling ship, anchored near the coast. It was their only chance for salvation.

When a whale entered the bay, the captain and navigator of the English ship boarded a small boat and rowed in pursuit. At once, the Dutch stormed the bigger ship and seized it. They forced its officers back on board and seized the navigator’s clothes until he promised to guide them home. After a hazardous journey they arrived off the Norwegian coast – where they could not resist pursuing two ships, which if stolen and sold would have helped them recoup the profits they lost at Svalbard. Yet in the chaos of the pursuit the English officers regained control. They brought the Dutch crew to Spanish-controlled Belgium, and delivered them “into the hands of justice.”

Such stories were common across the seventeenth-century Arctic. Piracy, privateering, naval raids, and petty fighting routinely broke out between Europeans in the service of companies and countries vying for a stake in the resources of the far north. Since then, the Arctic has become a more peaceful – albeit more heavily militarized – region. Yet some political scientists and military officers warn that violent competition could return to the Arctic as global warming thaws sea ice that once blocked lucrative trade routes and hydrocarbon reserves. Popular articles and books now predict a return to the anarchic Arctic of the seventeenth century – or perhaps something much worse.

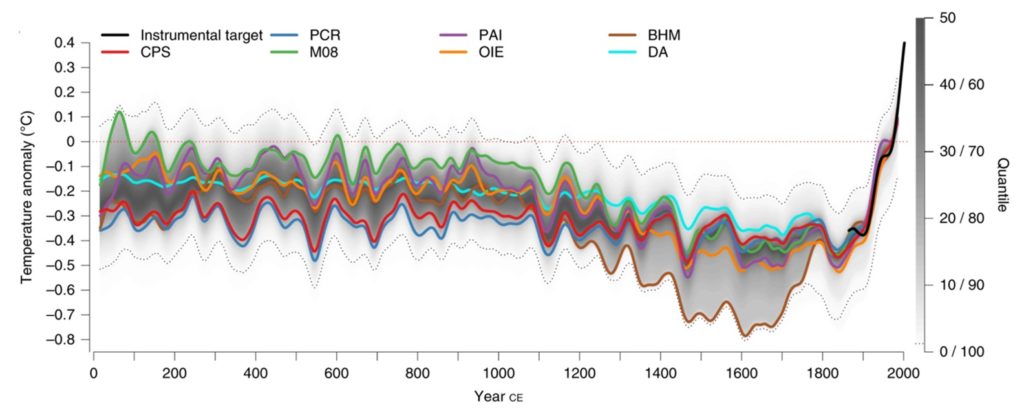

Few of these accounts consider history. After all the speed, magnitude, and cause of today’s global warming has no precedent in the history of the Holocene, our current geological epoch. Yet by unearthing evidence for past climates in everything from tree rings to ice cores, archaeological ruins to oral histories, paleoclimatologists and historical climatologists have discovered that, even in the Holocene, relatively modest, natural climate changes did meaningfully alter regional environments. In the seventeenth century, for example, volcanic eruptions temporarily shrouded much of the Earth in veils of sunlight-scattering dust. In the face of such “forcing,” the Arctic cooled in the early seventeenth century, warmed briefly, and then cooled even more than it had before.

Global temperatures over the past 2,000 years, according to different statistical methods. The black line represents modern warming as measured by meteorological instruments.

Climate change therefore coincided with competition and conflict in the seventeenth-century Arctic. For historians of climate and society – also called climate historians – both the time and place can function as a giant laboratory experiment, one that lets us test whether climate change really compels violence, in the far north and elsewhere.

Nowhere in the Arctic was competition between seventeenth-century Europeans fiercer than in the seas off Svalbard and the nearby island of Jan Mayen. There, colliding currents churned up nutrients from the deep ocean for as many as 100,000 bowhead whales. At over 100 tons, the whales were and are among the largest animals to ever live – and among the most intelligent. Bowhead behavior in courtship, feeding, and migration is so complex that it constitutes culture: a constellation of learned practices assumed by an entire community. Yet bowheads are also slow, mild-mannered, and therefore relatively easy to kill. Their bodies are lined with thick blubber that could be boiled to render oil, and their mouths bristle with baleen plates once coveted by dressmakers.

For whalers, bowheads were therefore irresistible targets – especially in bays along Svalbard and Jan Mayen, where they congregated in huge numbers. When whalers killed a bowhead there, they would strip away its blubber, rip out its baleen hairs, row the blubber and hairs to the coast, boil the blubber in makeshift furnaces, pour oil rendered from the blubber into barrels, and haul everything aboard their ships. These techniques allowed whalers to hunt in some of the most forbidding environments on Earth.

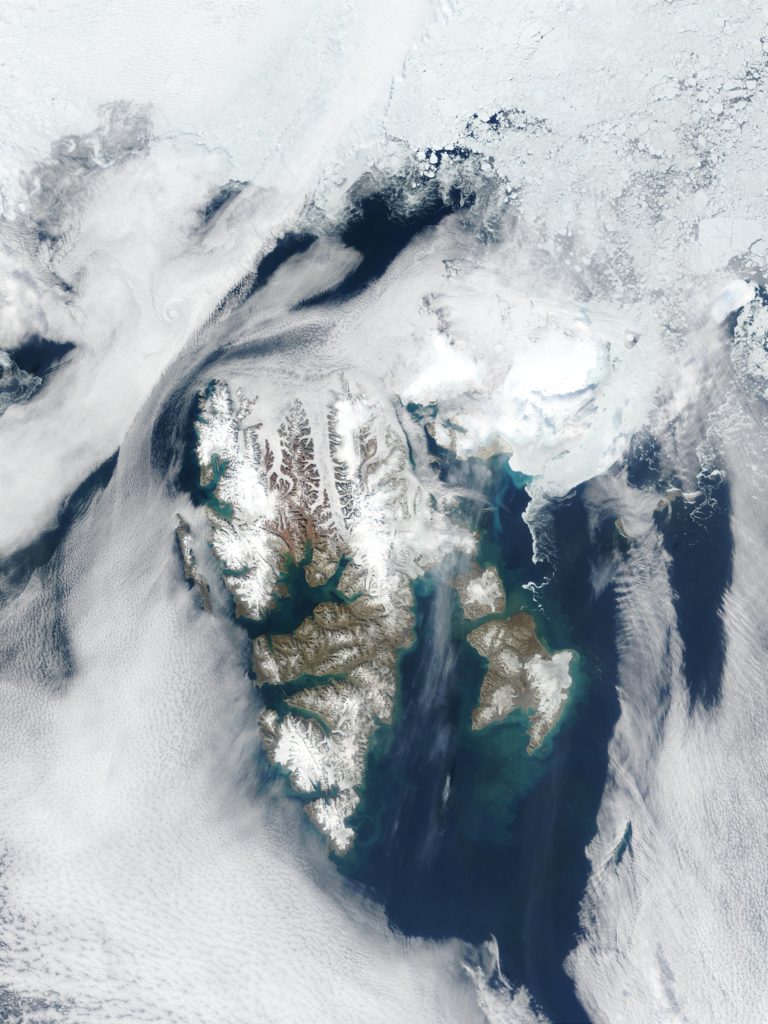

A summer view of Svalbard today, as seen from space. Sea ice around the archipelago was far more extensive in the seventeenth century. NASA.

Yet the same techniques also encouraged violence between whalers and sailors from competing companies and countries. Whalers soon learned to exploit bowhead behavior by attacking only those whale pods that seemed about to leave a bay. If they were careful, the rest of the whales would ignore the disturbance. However, if competing whalers killed whales from coastal encampments in different parts of the same bay, pods would scatter, and panicked whales would escape the bay. England’s Muscovy Company therefore enlisted warships to keep their rivals – the Dutch in particular – out of Svalbard’s bays. The Dutch Northern Company argued that its whalers should be able to hunt whales wherever they liked and dispatched them with their own heavily-armed escorts.

The threat of violence must have been daunting for many whalers. Yet they had greater reason to fear the frozen ocean: the “sea ice” that slowly melted in the summer and returned with a vengeance in winter. Sea ice could take many forms: “fast ice” when anchored to the coast; “drift ice” when detached from the shore; and “pack ice” when clumped tightly together. Often, it was thick and hard enough to shatter ships, pervasive enough to block movement, and fast enough to surprise even experienced sailors.

Sea ice in all its varieties responded both to weather and to the climatic trends of the seventeenth century. In the cold early decades of the century, sea ice typically lingered deep into the summer in bays along Svalbard and Jan Mayen. When that happened, neither whales nor whalers could enter those bays. In the chilliest summers, only a few of Svalbard’s many bays were entirely free of ice. Yet because Svalbard is at the volatile intersection of major currents in the atmosphere and ocean, its weather has long been unpredictable. Across the archipelago and in nearby Jan Mayen, warm years repeatedly interrupted even the coldest stretches of the seventeenth century. Just about every bay could then be free of ice for most of the summer, and whalers could easily hunt whales along the coast.

Ironically, it was in the coldest years that whales were easiest to hunt around Svalbard and Jan Mayen. Since they would all congregate in just a few ice-free bays, they were easy pickings for careful whalers. Heavily armed whaling fleets would confront one another in the same bays, equipped not only with guns but also with competing legal claims to the spoils. Yet in every cold year, Dutch and English whalers decided to cooperate rather than fight. It was simple math: a clash between two united fleets would have been so costly in blood and treasure that the year’s profits would be entirely wiped out.

Warm years turned out to be the most dangerous. With little sea ice to stop them, whaling fleets scattered into many different bays. In that context, soldiers aboard English warships decided to hunt down isolated and therefore vulnerable whaling ships owned by rival companies and countries. Yet when they warned whalers aboard those ships to leave Svalbard, the whalers would simply sail to the next available bay. After they were spotted a second or a third time by English soldiers, fighting usually broke out.

Overall, climatic cooling reduced the odds of bloodshed between whalers in the early seventeenth century. Warm years, however, were violent years: exactly what some expect for the Arctic of the future. Still, all is not as it appears. Cold years had the same effect in the seventeenth century as hot years will likely have now: they made it easier for corporate employees to exploit a coveted resource. It was in fact exactly when cooling made that resource more accessible that whalers set aside their differences and cooperated. Links between climate change and conflict turned out to be exactly the reverse of what some anticipate for our hotter future.

A seventeenth-century painting depicts sailors pursuing bowhead whales near a temporary encampment off Svalbard. Abraham Storck, Walvisvangst bij de kust van Spitsbergen, 1690. Stichting Rijksmuseum, Zuiderzeemuseum.

The whales and whalers of the seventeenth century also teach us that links between climate change and conflict involve much more than the causes of violence. Beginning in 1619, rival whaling companies decided to build permanent camps in different parts of Svalbard and Jan Mayen, both to reduce the odds of conflict and to catch whales more efficiently. The new arrangement worked well, especially for the Dutch, who built a sprawling settlement, Smeerenburg (“Blubbertown”) on the northwestern tip of Svalbard.

Yet the camps quickly became tempting targets for pirates, who discovered that they could steal bowhead bones and blubber just before and after whaling fleets arrived every summer. The Muscovy and Northern companies decided that the only solution would be to fortify and then colonize the camps year-round. The Muscovy Company’s directors offered condemned criminals freedom, and generous compensation, if they would only stay the winter. Yet when they arrived at Svalbard, the first volunteers supposedly felt “such a horrour and inward feare” at the prospect of overwintering that they elected to face justice at home rather than remain.

The Northern Company initially had better luck. After Basque pirates plundered the company’s well-stocked settlement on Jan Mayen, two teams of Dutch volunteers attempted to overwinter in both Jan Mayen and Smeerenburg. Unfortunately, they had the misfortune of attempting the feat in the early 1630s: perhaps the coldest stretch of the early seventeenth century in that region. Miraculously, the Svalbard volunteers survived, but their colleagues on Jan Mayen perished just before the whaling fleet arrived in the spring. A second attempt to overwinter at Smeerenburg ended in the death of every volunteer, dooming the Northern Company’s attempt to colonize the Arctic.

A Dutch representation of Smeerenburg at its peak. Cornelis de Man, Traankokerijen bij het dorp Smerenburg (1639), Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

The threat of piracy had in effect exposed Dutch whalers to some of the most dangerous weather of the seventeenth century. Here, then, is another hard-won lesson from the past. Climate change, it turns out, not only affects the odds of violence breaking out, but violence and the threat of violence also increase the vulnerability of people and communities to climate change. Those most vulnerable were and remain at the bottom of social hierarchies. No director of any whaling company volunteered to colonize the Arctic, after all.

Soon after Dutch colonization attempts failed in the Arctic, the region warmed for over a decade. Because bowheads suffer from heat stress in warm water, many whales followed the edge of the pack ice as it retreated from Spitsbergen and Jan Mayen, so that there were often fewer to hunt near whaling settlements. Yet even before the Arctic started to warm, whalers reported that bowheads were learning to avoid those settlements. By the middle of the seventeenth century, the whales had changed a culture that long hinged on annual migrations between islands, along routes passed down the generations from mothers to calves. Whalers even observed that many bowheads had become skittish and difficult to approach even at sea, while others learned to escape pursuit by swimming under the porous edge of the pack ice and surfacing behind it in unreachable pockets of water.

It was in this context that the Arctic abruptly cooled in the late seventeenth century. To their dismay, Dutch whalers found that sea ice routinely blocked the coast around Smeerenburg and Jan Mayen for much of the summer. Most bowheads lingered near the edge of the pack ice but stayed far from the shore. With the whales far out at sea and settlements surrounded by ice, it must have seemed like there was little hope for the whaling industry.

Yet Dutch whalers adapted quickly. Reports of colder weather in the Arctic likely inspired shipwrights to harden and grease the hulls of whaling ships so they could survive and slip away from collisions with thick sea ice. Whalers learned how to rip blubber off whale carcasses while out at sea, or perhaps while balanced precariously on sea ice. From Basques they also learned how to boil blubber at sea – a risky business aboard wooden sailing ships – and then how to haul blubber directly from the Arctic to furnaces in Amsterdam. There, laborers boiled oil with a purity never achieved in the Arctic, giving Dutch whalers a competitive edge in the European market. Meanwhile, the Dutch government allowed a corporate monopoly on whaling to expire, dooming the Northern Company but encouraging thousands of independent whalers to join the industry.

As they grew in size, Dutch whaling fleets became irresistible targets for naval squadrons fielded by hostile European nations. Successful adaptations to climate change by whalers and whales had, in effect, encouraged more violence in the Arctic. Yet those adaptations had also changed how violence could occur. Rather than squaring off along the coast of Arctic islands, Dutch, English, and now French warships fought out at sea, along the labyrinthine edge of the pack ice. Dutch whalers eventually learned to use the ice to escape pursuit or even ambush isolated warships.

Here, a third lesson from the past: in the Arctic and elsewhere, climate change transforms environments in which wars are fought. It therefore changes the tactics that combatants may use to defeat their opponents, in addition to changing the strategic calculus that makes violence more or less likely. The most immediate connection between climate change and conflict may unfold on this tactical level – and it is a connection still widely ignored by journalists and policymakers.

Sea ice off Svalbard, July 2019. Photo by Bathsheba Demuth, Brown University.

Now more than ever, our future on a changing planet is hard to foretell. In the Holocene, natural climate changes – even those of the Little Ice Age – were globally modest in scope. Today’s rapid warming therefore poses unprecedented challenges, in the Arctic and elsewhere. Yet even past climate changes could work through Earth’s complex systems of atmospheric and oceanic circulation to profoundly alter local environments. Together, scientists, archaeologists, and historians are uncovering human responses to those changes that shed much-needed light on the threats we should anticipate in the coming decades.

The history of the seventeenth-century Arctic suggests that warming need not provoke more violence between countries and communities. Yet it also indicates that too much attention has been focused on whether climate change will provoke conflict, rather than how preparations for conflict could exacerbate social vulnerabilities to climate change – or how climate change could alter the ways in which conflict can unfold. To better understand the geopolitical implications of climate change, we urgently need histories that teach us to consider relationships that might otherwise escape our attention. Only by considering the past can we develop truly forward-thinking policy.

A longer version of this article will appear in the March 2022 issue of the American Historical Review.

***

Dr Dagomar Degroot is an associate professor of environmental history at Georgetown University. His first book, The Frigid Golden Age, was published by Cambridge University Press in 2018; his next book, Ripples in the Cosmic Ocean, is under contract with Harvard University Press and Viking. He publishes equally in both historical and scientific journals, most recently for Nature, Environmental History, and Environment and History. He is co-director of the Climate History Network and HistoricalClimatology.com, co-host of the podcast Climate History, and writes for a popular audience in publications that include the Washington Post and Aeon Magazine.

***

‘Environment & History’ (2021) is a collection of 13 articles exploring new historical research on the environment and climate change from scholars worldwide. In each case attention is paid to present-day lessons and applications of historical understanding of the environment and climate. The series was generously funded by the Scouloudi Foundation and edited by Dr Sarah Johanesen. The complete set of 13 articles is available here.

‘Environment & History’ (2021) is a collection of 13 articles exploring new historical research on the environment and climate change from scholars worldwide. In each case attention is paid to present-day lessons and applications of historical understanding of the environment and climate. The series was generously funded by the Scouloudi Foundation and edited by Dr Sarah Johanesen. The complete set of 13 articles is available here.