In this three part series, Amy Todd explores the lives and work of key figures within peace activist networks in the UK. Each blog will tell the story of an activist contextualised within a key time for the women’s peace movement. The series will explore the relationship between feminist, pacifist and anti-military ideologies to give a brief timeline of the history of female peace activism.

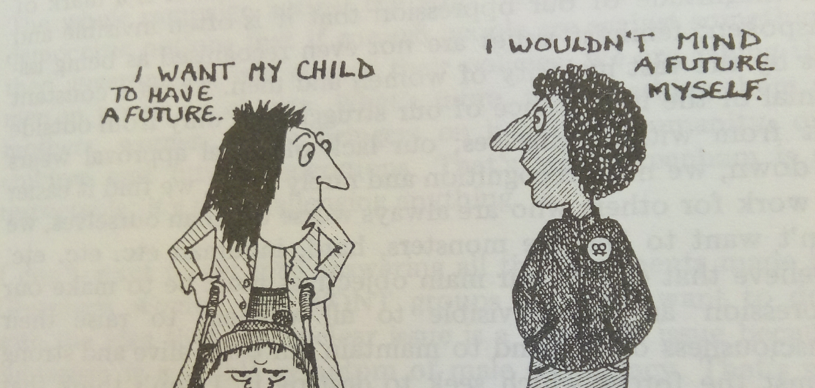

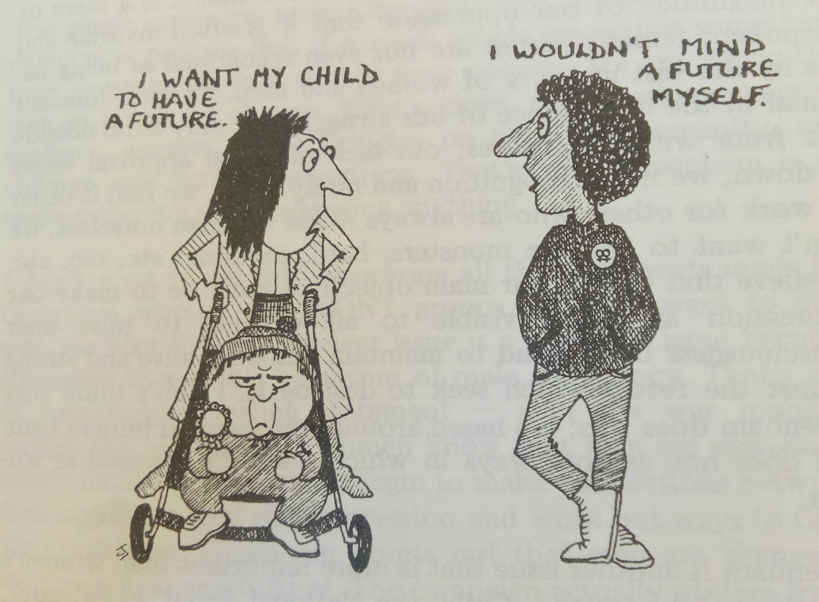

Pat Arrowsmith was one organisers of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament’s first Aldermaston March in 1958 and still serves as a CND vice-president today. The march to Aldermaston took place shortly after Britain had conducted its first H-bomb test at Christmas Island in the Pacific Ocean. 10,000 people started the march in Trafalgar Square, waving banners, singing songs and even pushing children in prams. Those gathered marched through poor weather over the next four days for the 50 mile journey to Aldermaston in Berkshire. CND would become the predominant anti-nuclear movement in the UK, working for global peace with campaigns that included ‘No to NATO’ and ‘No to Trident.’

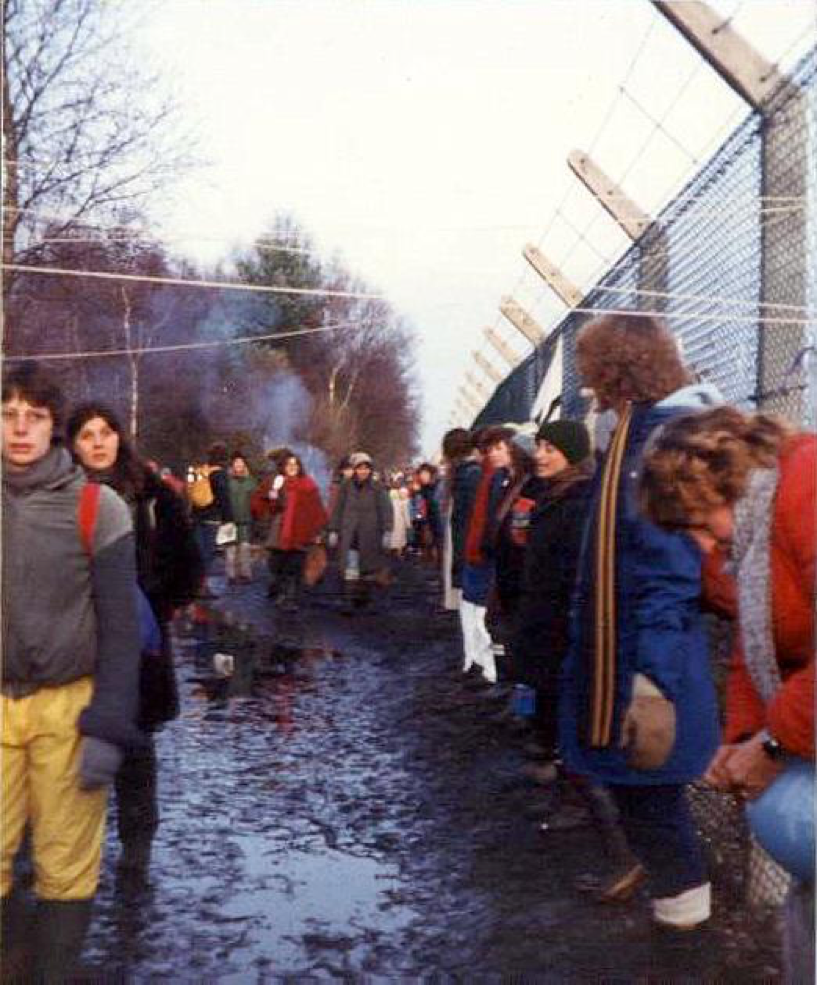

Pat continued her work on nuclear disarmament later at Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in the 1980’s, inspired by the Aldermaston march. At Greenham, over 30,000 women joined together to protest against nuclear armament in the UK. The movement began humbly when 36 Welsh women that decided to take a stance to secure their children’s future in the face of nuclear war, and set off on a 10 day protest walk to the RAF base at Greenham, Berkshire.

The years between the first CND march to Aldermaston and the establishment of the peace camp at Greenham were transformational within the larger feminist movement. Debates over women’s rights and equality in the 1970s placed issues such as equal pay, access to contraception, and debates over systems of childcare at the forefront of feminist consciousness. Women peace campaigners splintered into different groups, much like suffrage campaigners during the First World War. Some feminist groups took issue with actions or slogans that rested on maternal values and suggested that campaigners were focusing on patriarchal views of women as natural peace-makers. These tactics included decorating the military base fence which pictures of their children and children’s clothing. They were scrutinised by radical feminist and lesbian groups because they emphasised maternalism and leaned on traditional stereotypes to achieve short term objectives, rather than challenging the patriarchal assumptions which underpinned these stereotypes. Notably, Pat does not label herself a feminist and described herself as more of a ‘socialist and pacifist’ in a 2008 interview with The Guardian.

This is a conflict that has stretched across this three-part series on Women and Peace; many pioneering peace campaigners were women who used their gender identity to suggest their voices should be heard as wives and mothers. Although they served active, public roles and sought to shape public attitudes to conflict, they did not use their activist platforms to emphasise the need for reform for women’s rights as citizens or the place of women in society. Pat herself did not use her platform for the advancement of feminist causes even though she did support campaigns for LGBT rights.

Senate House Library’s Special Collections holds several pamphlets that shed light on the feminist debates within the women’s peace movement. In a collection of feminist papers called Breaching the Peace , one writer states, ‘it seems to me, in truth, the women’s peace movement is one enormous, seductive con – a splendid method for eliminating the women’s liberation movement’. In a pamphlet issued in response called Ragying Womyn: In Reply to Breaching the Peace, author Jean Freer argued that Greenham could further the work done by feminists by brining about political awakening at the camp, as, ‘for many comfortable bourgeoise… being roughly handled by police or sneered at in Sainsburys in Newbury begins an awareness that can lead to a recognition of the continuous struggle in so many peoples lives’.

The 30,000 encamped at Greenham did not have a uniform definition of peace-making, or an agreed sense of their objectives as women. According to Elizabeth Fraser and Kimberley Hutchings, heated discussions took place at the camps. Women debated the causal connection between war, patriarchy and violence; whether violence in the name of peace could ever be justified, and the appropriate stance on non-violent resistance. The demonstrations at Greenham were not indicative of a ‘passive’ kind of pacifism, but a kind of anti-militarism where civil disobedience, prison sentences, direct action and serious organisation were employed. Pat herself was imprisoned eleven times during her activism, including an 18 month sentence for leafletting soldiers with CND material which led to her recognition by Amnesty International as ‘prisoner of conscience’.

This series has provided a brief history of key figures within the women’s peace movement from the 1870s to the 1970s. Aside from describing the remarkable achievements of accomplished women activists, the series has described the sometimes conflicting relationship between feminist movements and gendered peace activism. However, the activism of Pat Arrowhead, Helen Crawfurd and Hannah Peckover illustrates the long history of committed political activism by pacifist women in the UK. At times, their feminist, Christian, internationalist or socialist ideologies worked in concert with their pacifism, and contributed to expansion of the national or international peace organisations that they operated. Far from being a male dominated arena, women have had a significant role in the development of peace movements. The relationship between feminism, non-violence, gender and peace deserves much further investigation and consideration by future scholars and researchers.

Amy Todd is the Public Engagement Officer for the Layers of London project at the Institute of Historical Research, and a student on the Public History MA programme at Birkbeck, University of London.

Listen to a podcast that accompanies this series. Amy interviews Pat Gaffney (Pax Christi) and Liz Khan (Women in Black) to discuss their personal experiences in peace activism, and contemporary issues in gendered peace work.