In this three part series, Amy Todd explores the lives and work of key figures within peace activist networks in the UK. Each blog will tell the story of an activist contextualised within a key time for the women’s peace movement. The series will explore the relationship between feminist, pacifist and anti-military ideologies to give a brief timeline of the history of female peace activism.

After the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War (1870 – 1871), Hannah Priscilla Peckover of Wisbech, Cambridge, a staunch Quaker, committed herself to protesting against the suffering caused by war.

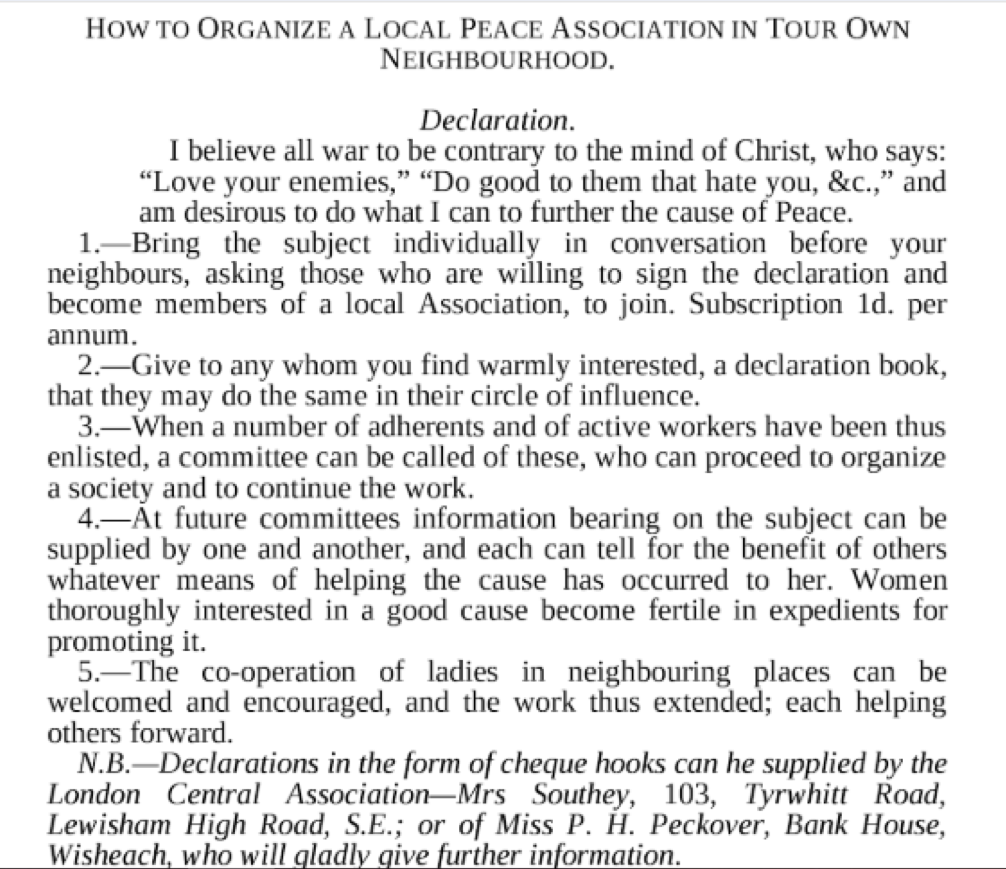

In 1879, at the age of 46 and without previously being involved in peace activism, Hannah founded the Women’s Local Peace Association, a branch of the wider Peace Society Ladies Auxiliary. She was frustrated by the lack of active campaigning in the Cambridge area, and said, ‘It seemed to me a disgrace that only two hundred women could be found who believed in Peace’ when asked about her sudden pacifist activism.’ She became tirelessly involved in building support from the local community, and the branch soon had over 6000 members. Hannah worked by going door-to-door and asking her neighbours to show their personal commitment by joining the association and handing out their ‘declaration’, which included guidelines for behaviour and how to create your own peace association. Hannah also authored the Peace and Goodwill publication, which ‘campaigned for the establishment of a court of nations and the reduction of all armed forces, with a view to their eventual abolition’. Heloise Brown discusses this further her excellent book, Truest Form of Patriotism: Pacfist Feminism in Britain 1870-1902. Remarkably, Hannah learned 16 languages to communicate her message in global peace campaign materials.

Hannah’s commitment to peace activism was rooted in her Quaker faith, a common trait among her contemporaries in the peace movement. Late 19th century Quakerism taught, as it does today, that everyone has God within them; members were encouraged to demonstrate their committment to a Peace Testimony to emphasise that non-violence and reconciliation were superior to violence. Hannah explained that her work in peace-making followed as a result of her commitment to following Christ’s example.

Hannah was by no means a feminist. Heloise Brown argues that Hannah relied on the gendered behavioural norms of her time by using skills in co-operation and persuasion and focusing on women’s domestic responsibilities. Her absolute pacifism encouraged a tendency to passivity; her activism was often enacted through prayer and meeting with other peace groups, rather than direct action. When asked about the role of women in society, she replied that she did not believe the right to vote would be necessary for women to be able play a role in peace-making, as, in her view, ‘women had influence as citizens, regardless of their position as non-voters’. She believed that women should be encouraged to join peace organisations and told women to recruit others as the ‘gentleness of their nature might pre-dispose them to gather round the banner of Peace and Goodwill’. She thought women were ‘natural peace-makers’ and often leaned on maternalism in her rhetoric.

Hannah has often been excluded from the story of the Peace Movement in the UK, or is simply referenced as an ‘optismistic Christian Pacifist’ by Paul Laity in his The British Peace Movement 1870-1914, despite being nominated Nobel Peace Prize four times and going on to establish Annual Peace Sunday celebrations. As a Quaker woman, she was pioneering in her dogmatic determination to spread the message of peace at a time of war, and the important place of religion in the history of peace-making in the UK. Her story also points to some of the internal conflict within engendered peace work, a narrative that will be explored further in the rest of this blog series.

Amy Todd is the Public Engagement Officer for the Layers of London project at the Institute of Historical Research, and a student on the Public History MA programme at Birkbeck, University of London.

Listen to a podcast that accompanies this series. Amy interviews Pat Gaffney (Pax Christi) and Liz Khan (Women in Black) to discuss their personal experiences in peace activism, and contemporary issues in gendered peace work.