Professor Philip Murphy’s blog post responds to a new BBIH online reading list of 606 publications focusing on the history of monarchy and coronations in Britain and Ireland from 1485 to the present day. The list specifically covers:

- Succession, royal, a subcategory of Monarchy (within Political, administrative and legal history)

- Coronations, a subcategory of Ceremonies (within Other topics)

We have become used to thinking of the current moment in British politics as being uniquely prone to ‘culture wars’. The symbolism of the smallest detail in public life is pored over by an army of commentators, constantly on the lookout for sources of indignation and offense. Inevitably then, the arrangements for the Coronation, an event which (as many items on the BBIH reading list will testify in relation to previous reigns) is saturated with all manner of symbolism, has become the subject of fierce partisan debate. Meanwhile, there are signs that the public as a whole is far less interested in what will happen on Saturday 6 May than the tabloids and the commentariat. 64% of respondents to a recent YouGov poll said they didn’t care very much or at all about the Coronation, a figure that rose to 75% for the 18-24 age group. And a remarkable 51% felt the event shouldn’t be funded by the taxpayer.

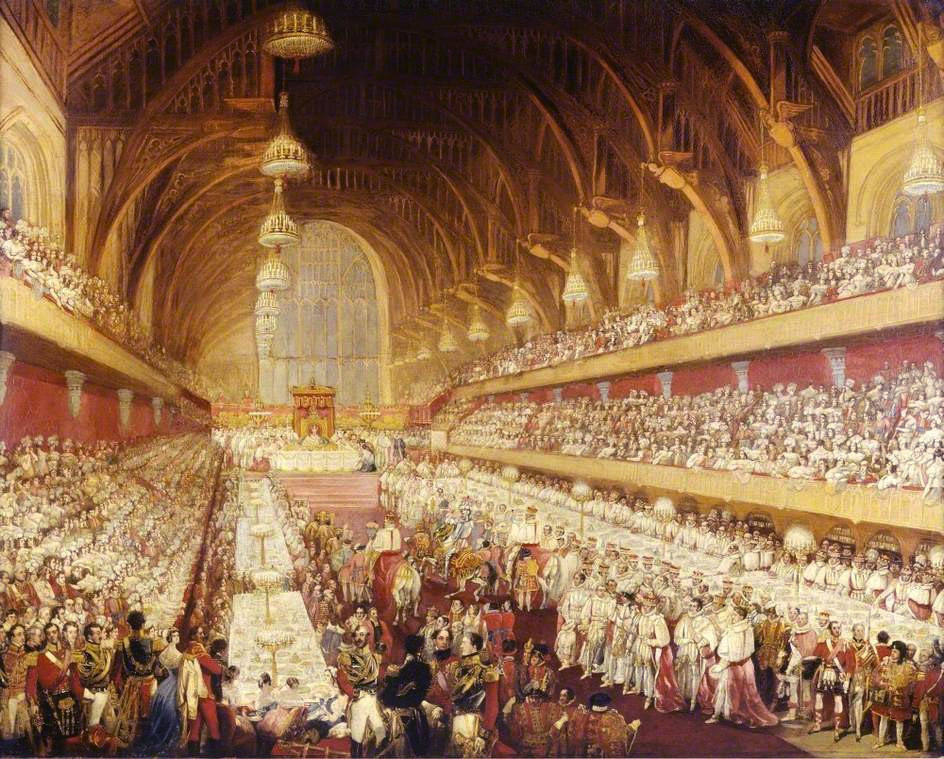

George IV’s coronation banquet was held in Westminster Hall in the Palace of Westminster in 1821; it was the last such banquet held. (Wikipedia)

While this apparent weakening in public support for the monarchy might provide little comfort for those on the right of the political spectrum, Daily Telegraph columnist Philip Johnson managed rather inventively to suggest that this lack of enthusiasm was a consequence of the Coronation becoming too ‘demotic or inclusive of minorities’ (in effect then, too ‘woke’). Johnson even managed to detect sinister intent behind the choice of the humble quiche as the Coronation’s signature dish, asking whether this alcohol free, meat-free concoction wasn’t ‘just a wee bit bland’ to be ‘set before a king or consumed by his ravenous subjects’. Johnson’s argument was that by seeking to adapt the event to suit contemporary sensibilities, the Coronation’s choreographers had watered down tradition and hence reduced its popular appeal.

Yet what do we mean by ‘tradition’ and why should it be so sacrosanct? Anyone delving into the Bibliography of British and Irish History (BBIH) reading list on monarchy and coronations from 1485 to the present day will soon realise that this is a slippery term, and that a key reason for the survival of Western Europe’s remaining monarchies, including the House of Windsor, has been their capacity to adapt to changing circumstances. One of the most useful concepts in recent decades for historians of modern monarchy has been that of the ‘invention of tradition’, explored in Eric Hobsbawm and Terry Ranger’s landmark volume of essays published in 1983. The contribution to the collection by former IHR director, David Cannadine, suggested that some of what we regard as the ancient trappings of the British monarchy were in fact dusted down, refined, and amplified as spectacle to meet the needs of political mobilisation and nation-building in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Writing for History & Policy, on the main elements of the Coronation service, David Pratt notes the ways in which these have evolved over the centuries, and suggests there is a place for a grown-up and historically-informed debate about how far they remain relevant to an increasingly secular and pluralistic society. My own 2013 book, Monarchy and the End of Empire, pointed to the willingness of the first post-war Conservative government to make changes to the rituals surrounding the accession and coronation of Elizabeth II so as not to offend Commonwealth members. This including dropping the term ‘Imperial Crown’ from her Accession Proclamation for fear that recently-independent India might object. Prime Minister Winston Churchill accepted this particular change only with the greatest reluctance, rightly asserting that its use long predated the creation of the British Empire. To this extent, the battle between ‘traditionalists’ and ‘modernisers’, which has become just another campaign in our contemporary culture wars, is nothing new. Indeed, the BBIH reading list points to the fact that the history of monarchy is one of adaptation, invention, and reinvention (in which there is probably room for a 21st century quiche).

Professor Philip Murphy is Director of History & Policy at the IHR. He is a Professor of British and Commonwealth History at the University of London and also joint editor of the Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. Philip is the Principal Investigator on the The Windrush Scandal in a Transnational and Commonwealth Context project. He teaches on the MA in History, Place & Community, for which he convenes the Place & Policy module.