This post was written by Millicent (Millie) Shepherd, undergraduate history student at the University of Leicester. She completed a placement at the IHR in July 2022, working on the Bibliography of British and Irish History and in the IHR library.

For as long as I can remember history has been a hobby of mine and, as the subject was familiar to me, it seemed fitting to study the subject at undergraduate level. I have still sought out challenges and exciting new opportunities, however, and currently find myself as an intern in the wonderful Institute of Historical Research. I’m not sure where I see myself going in the next 10 years of my life, where I will be working, or what I will be doing. One thing is for certain though, history and connecting with the public will be a part of it, the rest? Well, we will have to wait and see!

Work smarter, and not harder is an approach I have tried to harness during my studies as an undergraduate. Seeking out ways to minimise my time spent in front of the computer whilst simultaneously maximising the results I achieve. My time as an undergraduate student has flown by, particularly due to the impact of Covid-19. So, when it came to begin thinking about my dissertation my first reaction was panic.

When I eventually began to take a breath and realise that life beyond my student days could be exciting, I began to think rationally about my dissertation. The first question that came to my mind, aware of the 10,000-word task that lies ahead, was what can I do to make it easier to write and work on? I know from previous experience that my engagement with my work was based on how much I enjoyed and felt inspired by specific topics. Knowing this and knowing how important it was for me to be able to have fun with my work, led me to take a focus on crime, justice, the legal system, and women in eighteenth and nineteenth century England.

The topic of women and crime in the nineteenth century is surrounded by historiography which is so broad it makes the undertaking of studying the topic seem a monstrous task. Therefore, it is crucial to identify key texts which help to shape and focus my study, to make the task of delving into the scholarship seem less daunting. A good place to start would be Victoria Bates’ article, Under Cross-Examination She Fainted’: Sexual Crime and Swooning in the Victorian Courtroom. However, to take my work further and fully understand how women navigated society in a patriarchal climate (to help re-write the narrative and fully understand the picture), I need to delve into primary sources, more specifically primary sources which highlight how the eighteenth and nineteenth century woman experienced and viewed the world.

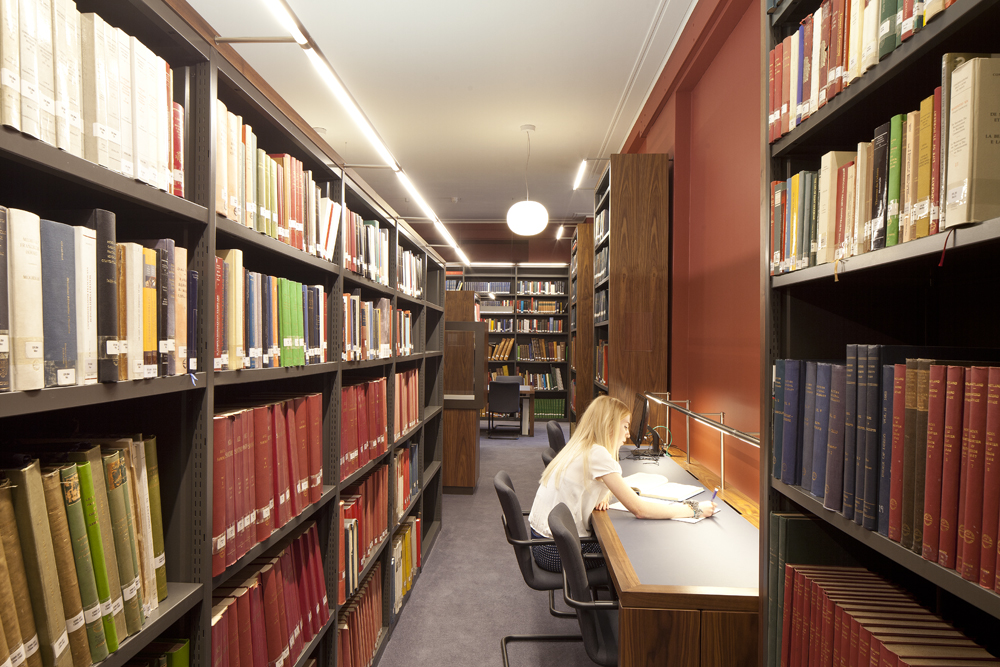

Thankfully I need not worry about finding such sources as the internship I am currently a part of has led me to the IHR library located in Senate House, London. Filled with a wealth of primary sources, covering a huge range of topics (the bookstacks even support the tower’s infrastructure!). I know as I write from a cosy corner, surrounded by beautifully bound books that could tell thousands of stories, that this is the right place to be to carry out any research topic. Following the advice of the wonderful librarian and internship mentors, I search the online catalogue and begin to take books from the shelves. One of these texts on laws of etiquette. Despite the first line of the ‘guide’ making me frown as to what was expected from women, this source prompted me to think about the larger implications of the behaviour expected from women, and my mind immediately goes to Hurl-Eamon’s Gender and Petty Violence in London which talks about women having an awareness of how the severity of a sexual assault or rape crime could influence the sentencing of the man (if he was sentenced at all) and how they too were also viewed. This then got me thinking, if a woman has expressed an awareness of the prejudices against them and how this can affect them in court, did they act on this? Or were they simply bystanders to something they viewed as a way of life?

Then when in the library during another research session I stumbled across the case of Madeline Smith in Crime and the respectable woman, who wouldn’t marry her lover, knowing the implications of such a ‘crime’. I was now developing my own research questions for my dissertation. Suddenly I have two examples of women in a ‘polite society’ who not only seem aware of the views regarding their behaviour and the implications this could have in court, but also how to limit the damage. Did women have agency in the court room?

Following two repetitive academic years of reading online texts from my bedroom, my experience in the IHR library has been one of academic growth for me. Having access to such a vast array of primary sources enabled me to link events together and most importantly develop my own questions. Inspired by what I have found and welcomed by the people there I will be returning to finish my dissertation research- in the place where the inspiration for it started.