This post was written by Jeremy Haslam, Senior Fellow at the IHR.

This might seem an odd conjunction of ideas. But in some of the historical work I have conducted over the last 40 years or so, the relationship this blog explores is important. This short note is, really, just a plea that historians become sensible of the idea that spatial considerations sometimes play key roles in building credible evidence-based historical narratives.

My work as an archaeologist over many years has led me to the position of discussing broad historical ideas, particularly concerning the development of late Anglo-Saxon institutions. This trajectory—by no means unique amongst archaeologists—has developed through recognition of the evidential value of spatial analysis, which is the backbone of all archaeological methodology. All archaeological excavation involves the elucidation of the spatial relationships between buried features; these relationships necessarily have an inbuilt sequential aspect. Sequential patterns can be recognised as developing in both time and space; since these have a human agency, they are therefore part of a historical narrative. The narratives developed by geologists are likewise based on the observation of sequences in rock strata caused by natural processes. Narratives are built up, and indeed constrained, by the evidences of particular sequences in both time and space. The interplay of the motivations and constraints in human agency in the past which underpin historical narratives can sometimes only be understood with these aspects in mind.

Read on, and the relevance of these observations will become clear.

Over the years I have developed an interest in two particular areas of historical enquiry which have grown directly from my interest in patterns, processes, and the application of spatial methodologies in the historical landscapes of England. The first is in the contexts that have shaped late Anglo-Saxon administrative developments, particularly from the reign of King Alfred in the late 9th century. These include burhs (newly-fortified quasi-urban settlements), burghal territories, hundreds, and shires, in both Wessex and Mercia. The second major interest has been how the spatial analysis of medieval urban morphology can act both as a generator of evidence-based narratives of urban development, and as an important corrective to some historical narratives which seem to be off-beam.

My aim here is not so much to rehearse old arguments, but to point to two contrasting instances in these fields of enquiry where spatial evidence matters—i.e. where it is an integral aspect of the evidence base which gives rise to and supports the narrative—and which can indeed generate a new or alternative narrative.

Late Saxon administrative developments

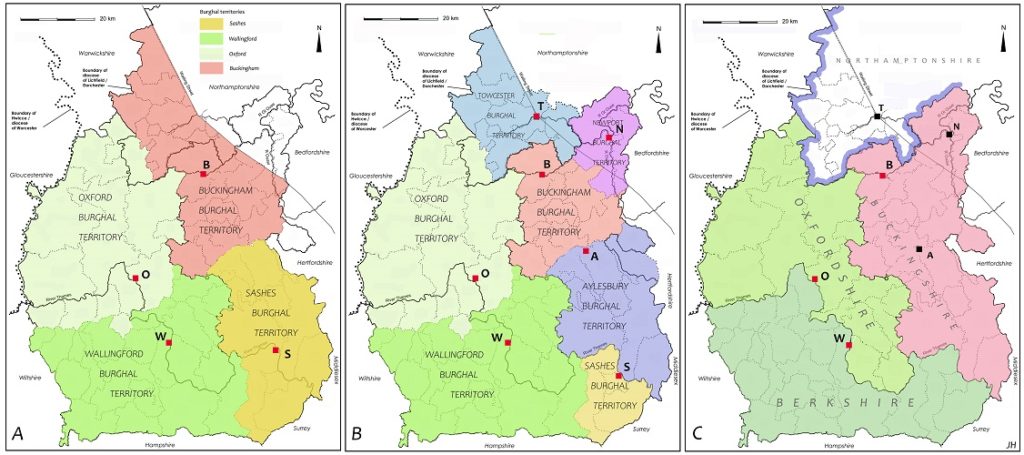

In my studies of the late Saxon document known as the Burghal Hidage I have come to the conclusion, based on several aspects of associated spatial analysis of the medieval landscapes which it covers, that the burhs which it lists formed part of an integrated system which was put in place at one moment in time by royal fiat. The purpose of this system was, firstly, to provide the whole of greater Wessex with a unified defence in depth against the predatory assaults of the Viking invaders; and secondly—and arguably as importantly—to enable the king to exert an all-embracing social, economic, as well as military control over the population. In other words, this was an exercise in the imposition of royal power, and a crucial stage in the development of the late Saxon state.

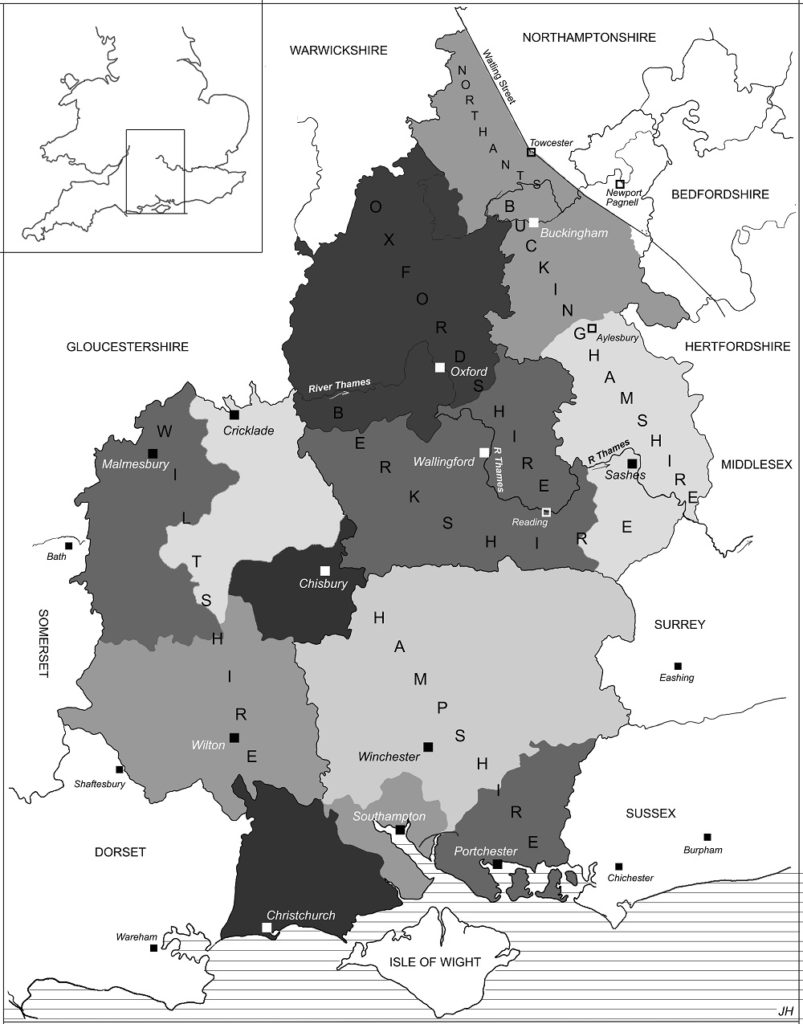

To this end, and to support the burhs, each burh was allocated a burghal territory, the landholders in which were obligated, by various forms of coercion, to support the king’s strategic and other social agendas at the burh. In Wessex the already-existing shires were divided up so that each burh was given a territory which was very roughly proportional to its size. A study of the hidages of the shires in Domesday Book, and the spatial distribution of the connections between urban tenements and rural estates, has enabled areas to be defined which correspond to the hidages stated in the Burghal Hidage document, and which represent the burghal territories. The fact that these burghal territories interlock over at least the central area of Wessex (see Fig. 1) shows that they were all part of a concurrent and unified system, rather than being formed one after another, as has been argued at length by others. This of course speaks volumes about the administrative sophistication of the Alfredian government machine in the late 9th century.

interlocking areas with the system of burhs instigated by King Alfred in probably the late 870s,

which were included in the Burghal Hidage document.

It also leads to the further inference that the Burghal Hidage document is all that remains of an original document recording an oath of allegiance of the whole of the population of Wessex to Alfred as king, since in recording the sum of all the territories attached to the burhs it recorded the lands of the whole of the kingdom. It was arguably the equivalent for King Alfred of what Domesday Book was for King William in 1087—the record of the landholdings in the kingdom as the basis on which all the landholders as a body gave their allegiance to the king by acclamation. Just as William required this from new subjects he had conquered, so Alfred would have required this after his victory over the Viking marauders in 879, to ensure their allegiance to himself rather than the Danes. This was especially important at a time when the Vikings had already subsumed every other independent kingdom of the time.

Without several stages of spatial analysis and inference in this somewhat convoluted argument, it would not be possible to gain any appreciation of the genius of Alfred as a far-sighted administrator—which indeed some have explicitly denied. But the evidence I have summarised tells a very different story.

A similar exercise in spatial analysis helps clarify issues concerning the formation of the shires and the hundreds as recorded in Domesday Book in the East and Central Midlands in probably the mid-10th century. This analysis gives crucial information which shows how this process came about by the amalgamation of the earlier burghal territories formed around new burhs in the period 911-917, some (but not all) of which are recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for these years—a development missed entirely by one distinguished historian. A draft of this research is available here, and is developed in a case study of how the burghal territory of the late 9th-century burh of Buckingham was transformed in stages to form the Domesday shire (summarised in Fig. 2). These spatial observations, and the inferences made possible by this evidence, will impact on any narrative dealing with the development of the important institutions of royal governance in these years.

Early medieval urban topography

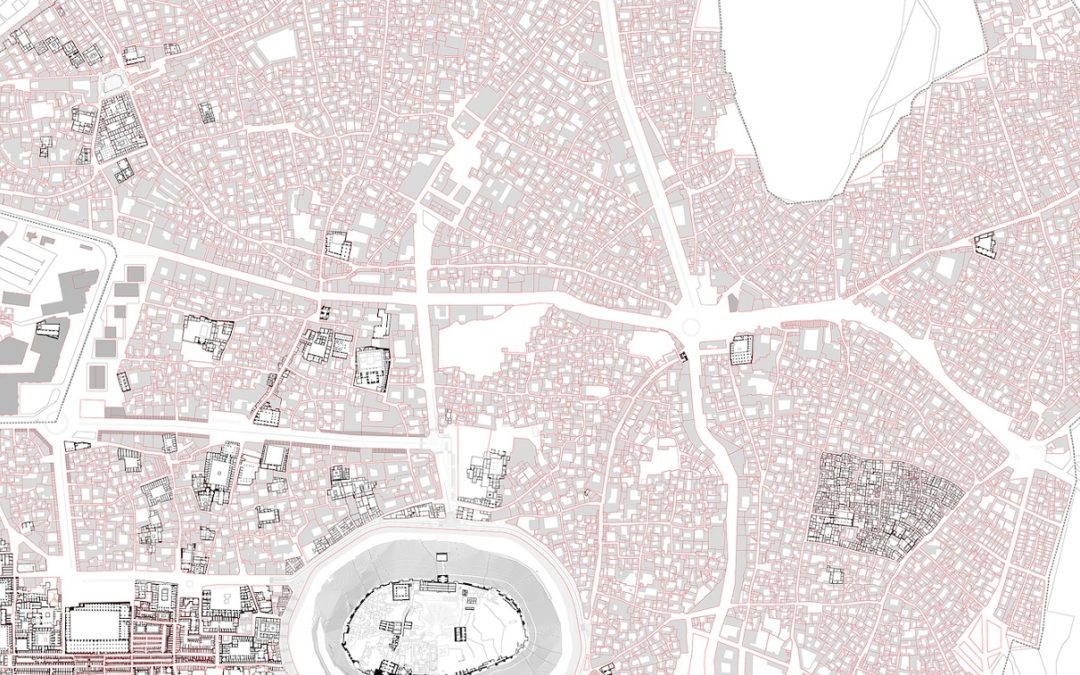

The second instance which demonstrates the importance of spatial analysis in the construction of historical narratives is the field of medieval urban topography. The analysis of the patterns of the layout of towns—town-plan analysis—is of course the meat and drink of the urban topographer and historian. My own work has concentrated on the way in which this spatial analysis needs to follow certain rules in making reasonable inferences from the interrelationships of different elements of the townscape. I argue that in some crucial cases these spatial deductions and inferences can challenge existing paradigms of interpretation, which process thus enables the development of more secure historical narratives.

Important here is the cast of thought inherent in an ‘archaeological’ way of analysing spatial patterns and relationships, which is characterised above. I have developed these rules in a paper which shows how an examination of the relationships between the patterns of burgages and streets in five towns of early medieval origin can lead to fresh ways of inferring processes involved in their origin and growth. From this it is possible to generate new historical narratives about the more general course of urban development from the late 9th to the 11th century.

This analysis is applied to Barnstaple, Devon, a late Saxon burh which replaced (or which may have been the site of) the Burghal Hidage burh of Pilton in the late 9th century. The relationship of the interlocking dependent burgages to one of the demonstrably primary streets leading to the east gate shows that these burgages were laid out at the same time as this street, the High Street, the gate, and the defences. The overall narrative of its origin which this evidence supports is that Barnstaple was laid out ab initio as a new defended planned town, with streets and burgages, as one element in the system of similar places put in place by King Alfred, arguably in the late 870s—a conclusion which not all historians would be inclined to accept.

In the case of Bridgnorth, Shropshire, a new town built around a castle in the early 12th century, a re-examination of the way in which burgages interlock at the corners of the principle streets laid out at right angles shows that these streets must have been planned concurrently, rather than successively, as had been previously thought by a number of historians. The town can, therefore, be seen as being planned as a unitary ensemble at one point in time. Various lines of evidence suggest that the most likely occasion would have been when the king took control of the castle in the very early years of the 12th century. At this time it appears that he created a large, but undefended, new town as a new colonising enterprise in hostile territory.

A similar conclusion can be drawn in relation to the early development of Ludlow, also in Shropshire, a castle town of the 12th century. This has been seen by historians and historical geographers since the classic studies of its topography by M R G Conzen in 1968 and 1988—and there are quite a few of them—as a palimpsest whose internal layout was developed in stages, being later surrounded by a town wall. But the analysis of the spatial inter-relationships of its morphological features, using the same type of ‘archaeological’ analysis as was applied to Bridgnorth and other places, has shown quite clearly that this cannot be the case. It can be concluded on the basis of this evidence that the main part of the town was planned and laid out as a single entity, concurrent with the building of its town wall. Although this has not met with the agreement of at least one commentator on the subject (to whose critique I have briefly replied), this conclusion does, in my view, make more sense of the overall morphology of the town and the larger narrative of its place in the development of planned castle towns at a crucial period in the history of the area.

As is shown in the cases of both Bridgnorth and Ludlow, a common tendency in much recent town-plan analysis—which views distinctive areas within a town’s morphology as sequential growth stages—is called into question by the rule-based analysis of the spatial patterns embedded in its topography, briefly described above.

Jeremy Haslam has worked as an archaeologist for many years, concentrating on late Saxon and early medieval sites, and has published numerous papers in archaeological and historical journals on urban history, archaeology, and town-plan analysis, and the development of late Saxon governmental institutions.