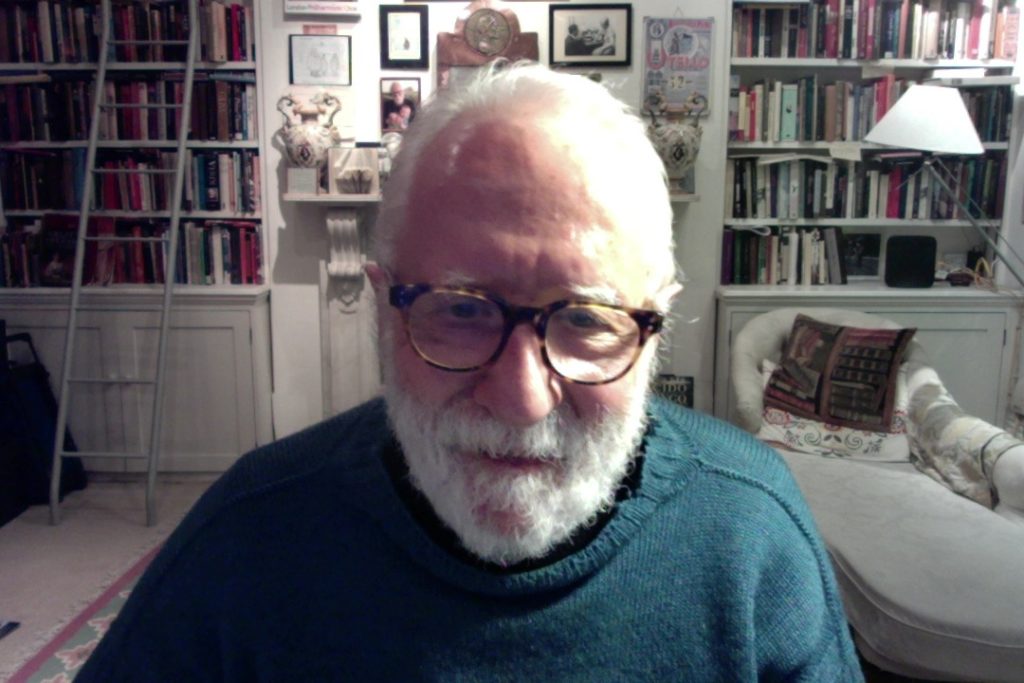

By Daniel Snowman, Senior Fellow, IHR

This is the second in a series of three blog pieces by IHR Senior Fellow, Daniel Snowman, raising provocative issues about how we regard and memorialise what we think of as ‘history’. These will be published monthly. Read the first blog here.

Why do history books begin at the beginning and end at the end? Not all of them, of course. Some historians combine straightforward chronology with theme, while others feature the life and times of a particular community or group of people. Others, like screenwriters or playwrights, incorporate flashbacks (or flashforwards) into an otherwise chronological narrative. But few serious historians dispense entirely with chronology. The sequential passage of time gives us a sense of our own place in the wider scheme of things, anchoring us firmly in the otherwise unnavigable waters of past, present, and future. If we lose our sense of time, whether through dreams, drugs, or dementia, we become helplessly disoriented.

I would like to suggest, however, at least as an experiment, that we stand traditional views of chronology on their head so that, instead of starting at the beginning of the story and going forwards, we start at the end and unravel the story backwards (as in the 2002 film Irreversible, or Pinter’s Betrayal or Martin Amis’s experimental novel Time’s Arrow). This, after all, corresponds in some ways to how we situate ourselves in history. If I reflect on current events, whether in my own life or in the wider public sphere, I can develop a more informed view about how things got to be the way they are by looking backwards rather than focusing on where they might be leading. Looking ahead means guesswork, but looking back can be clarifying. And this was presumably just as true for our predecessors as they tried to make sense of their own lives. If, therefore, we want to know what it was like living in earlier times, we should perhaps turn around and face not “what came next” but “what came before”. Think of those vast family trees that have become popular. These are essentially of two kinds. Some start with an individual—a famous king or emperor, say—and show the multiplication of his progeny, and then of theirs, moving forwards through the centuries. Others begin at the end, with an individual (you or me perhaps), and show an efflorescence of ancestors above and before us.

I see no reason why history should not be written in either of these ways. And since it is less often done, let’s consider the case for starting in the present, then fanning out backwards into the past. Right now, I’m at home on a warm spring evening typing this article on my computer before emailing it off to the IHR. This innocent little sentence contains a good half-dozen themes, any of which might mark the end point of a rich historical inquiry. Take that computer: what it does, where it comes from, how it was assembled and marketed. How long have I had it, and what came before it? Do you remember “electronic” typewriters, and before them ordinary old Olivettis and Xerox copiers or, earlier still, carbon paper, fountain pens, bottles of Stephens ink, and blotting paper? Or quills? What did our parents and grandparents write with—and on—when they were young? How were their messages delivered, and responded to? And their parents? In no time, you find yourself deep into the historical development of mass literacy.

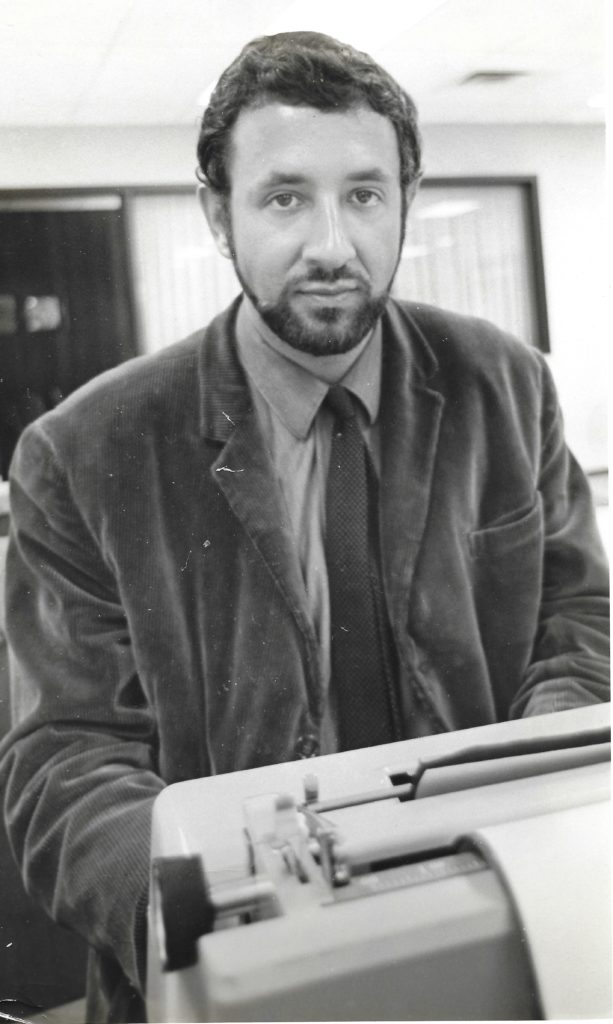

And who am I that am writing this article? The short-order House-that-Jack-built answer is that I am the author of a number of books and that I worked as a BBC producer for many years. I was recruited into BBC Radio in the late 1960s when they sought someone who knew American history and politics, subjects I was teaching at the University of Sussex at the time, having studied them as a post-graduate student at Cornell during the Kennedy years.

When I first crossed the Atlantic in the summer of ’61, I travelled by ship, with all my valuables locked away in a trunk. My parents waved me goodbye at Southampton docks. I was off to America, a romantic and optimistic New World led by a handsome and intelligent young man who wrote books, had been a war hero, and had a glamorous wife and family. There was an energising impatience to the Kennedy entourage as the President, succeeding the aged Eisenhower, talked of a “New Frontier” and of “getting this country moving again.” Eisenhower was revered for his war record, but widely regarded (at least among young political scientists at Ivy League universities) as a lacklustre leader in peacetime. Yet it was during his administration that the US Supreme Court outlawed “separate but equal” education for black and white children in the South—an historical landmark.

Not just education, but housing and health care, too, separated the races in the states of the Old Confederacy. At bus stations, there were separate waiting rooms and drinking fountains. “Negroes” routinely sat at the back of the bus, a convention famously challenged when the young Martin Luther King organised a bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, after a black woman, Rosa Parks, courageously sat at the front, causing outrage among local whites. When I first travelled through the South, these conventions still prevailed, widely accepted on both sides of the racial divide. But they were palpably weakening. Blacks, having recently fought and died in a world war against fascism and racism, returned to question traditional hometown conventions. During the war, blacks had served in the US Army in about the proportion (roughly 9%) that their numbers warranted. Almost a third of them were northerners whose families had come up from the southern states to escape the “Jim Crow” laws, and had settled in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Detroit, Chicago, a migration that helped nurture the jazz boom and the Harlem Renaissance of the inter-war years.

Many of these new northerners encountered severe economic conditions and de facto racism. But things were arguably even harder in the South during the Great Depression—not just for ‘Negro’ families, but for whites too. Many landed estates and farms were reduced to dust by drought and over-farming. John Steinbeck, in The Grapes of Wrath, paints a poignant picture of a family of “Okies” who, reduced to penury with their home foreclosed, pack all they have on a van and move west to California, the “Golden State.” The Joad family, and thousands like them, depended for finance on banks that, far from extending their loans, were suddenly calling them in. Northern finance had let down southern agriculture precipitately—or so it seemed to embittered dust bowl farmers like the Joads. Of course, the bankers themselves were in desperate straits. Yet many Southern farmers and plantation owners regarded their fate as a product of Yankee vindictiveness—a tradition that old-timers traced back to the period of “Reconstruction” when 20 years of selfish Northern triumphalism rubbed the nose of defeated Dixie in the dust. “Wouldn’t have happened if Abe Lincoln had lived,” they believed, a judgement many historians endorsed.

So, in brief, we’ve sketched a history here that begins in my office at home in 2022 and ends (arbitrarily) with events precipitated by the Confederate surrender at Appomattox in 1865—an example of a single historical thread that might emerge with a story told backwards rather than forwards. The actual subject matter, of course, is something the historian decides; it isn’t dictated by the methodology. From the same starting point, I could as well have moved backwards to my own birth in London on November 4, 1938—a few days before Kristallnacht, when the Nazis burned and destroyed Jewish synagogues, shops, and private premises throughout Germany. My parents were Jewish, and I’ve long wondered how my mother must have felt reading of these horrors with a new-born Jewish infant in her arms. She was 23. People married and reproduced younger in those days, one interesting thread for backward pursuit. And while my father and mother and three of my grandparents were born in England, their families had roots in the shtetls of Tsarist Russia and Eastern Europe…

You get the drift. Any of the themes I’ve touched on above could be expanded—with the necessary research—into a serious historical study: of the development of mass literacy, of transport, broadcasting, British or American academic life, Anglo-Jewry, Nazism, American race relations, Tsarist Russia, British immigration policy. And I haven’t even mentioned where I live, with whom, the kinds of homes I have lived in or the changes in my diet, clothing, or speech styles over the years. Start anywhere, and you can tell an illuminating story working backwards from effects to causes.

To be sure, telling history backwards is not free of problems. Just as conventional histories can be tedious, recounting one damn thing after another, so an unimaginative history moving backwards is equally dull if every “Z” leads to “Y,” then inexorably to “X.” There are further hazards. A few lines back I suggested working backwards from effects to causes. That notion is a minefield. Conventional historians often seem to confuse sequence with cause. Thus we read that Henry VIII’s infatuation with Ann Boleyn “led to” the Reformation, while the excesses of the French ancien régime “foreshadowed” the French Revolution. “Foreshadowing” and “leading to” are not the same as “causing.” For the historian telling the story backwards, the problem of apparent causality is acute: not everything is a direct result of the item that chronologically preceded it. And where does one end a history told backwards? With Adam and Eve?

But if there are problems with “counter-chronological” history, there are also benefits. Especially, perhaps, for teachers. Rather than plunge bewildered students into the origins of the American Constitution or the arcanae of Victorian politics, I’d ask mine what they’d had for breakfast, what they were wearing, how they’d travelled to the classroom, etc—and then push the questioning back, factor by factor, until we got into details of earlier industrial, economic, social, and political history. I did the same in the BBC in the late 1990s. Producing a Radio 4 series about previous “ends of centuries,” I decided to broadcast the programmes backwards, starting with the 1890s, followed a week later with the 1790s and so on until we reached the final programme, that on the 1390s. More listeners would tune in, I thought, if we began with Queen Victoria rather than Richard II. “If you want to know how things came to be like that,” each week’s closing announcement said in effect, “tune in next time!”

This approach to the past ties in with the current interest in genealogy and family trees. Try drafting your own family history backwards (as in the tv series “Who Do You Think You Are?”), starting with yourself as the initial focus. The text will gradually become augmented by material garnered from interviews with parents and older relatives, until individual memory merges with an ever-widening back-history.

Or consider the “micro” studies of particular people or communities in which historians have attempted to approach their data purely in its own terms. Thus, Le Roy Ladurie described life in a medieval Provençal town, Natalie Zemon Davis a returning French soldier who proved to be an impostor, Carlo Ginzburg a miller in a small Friuli town, and Robert Darnton a bunch of French apprentices massacring local cats. Each of these historians, like an anthropologist, drew wider lessons and implications from otherwise unremarkable data. None claimed that the story they told led to anything of subsequent historical significance. To the traditional historian telling a conventionally chronological history of France or Italy, therefore, Montaillou, Martin Guerre, or The Great Cat Massacre would be of little account. But if history were told backwards, such stories might emerge more prominently. And it is important that they should. For they help “situate” the specific and apparently inconsequential—that is to say, most of life!—as part of legitimate historical discourse.

In an age when people are said to live in a permanent present, telling history backwards can help to hook those not otherwise inclined to think about the continuities between past and present. As a device, it allows the historian, and the reader, to start with the familiar before moving on (backwards) to the less familiar and the general. By telling history “backwards”, therefore, we may find we can reinstate more of the specific and apparently inconsequential from the past. If so, we will greatly enrich our understanding of the present—surely, one of the fundamental goals of the study of history.

Daniel Snowman is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Historical Research, University of London