This post was written by Alex Kither, graduate trainee library assistant at the IHR library from September 2020 to July 2021.

On July 8, 2021, we celebrated the centenary of the Institute of Historical Research. The date marked one hundred years of lectures, seminars, conferences, publications and projects at the IHR. However, it also marked one hundred years of the library collections.

The library has played a central role in the institute since its conception and now holds a vast collection of nearly 200,000 volumes with sizable holdings on the history of Britain, Europe, Latin American, the US and Colonial History. Over the years these collections have passed between the custodianship of countless librarians, each with their own principles and practices. Beyond the type upon the pages, the collections of the Wohl Library stand as an historical monument in themselves; material evidence of one hundred years of donations, acquisitions and withdrawals, constantly being read and shelved, catalogued and stamped, lost and found.

The history of the book, the library and its users is a vibrant and expanding field of study all of its own. There are societies, journals and lectureships across the world dedicated to books, their creators, curators, and owners. This was the subject of a recent course with David Pearson, book historian and former Senate House Librarian, as part of the London Rare Book School. I was fortunate enough to have been provided funding by the IHR to undertake the course and learn more about identifying provenance in books.

With the knowledge gained from this course, I have gone through the shelves in the Wohl Library and picked out a few markings of provenance to illustrate the diversity of our collections and their origins. 200,000 books do not appear overnight. They accumulate over time. They arrive from all kinds of places, from all kinds of people, and sometimes they carry the markings of their past upon their spines, covers, paste downs and pages.

Book Labels, Bookplates and Heraldry

Book plate of French historian Fleury Vindry found in the ‘Catalogue des actes de François Ier’, (EF.442/Fra).

Historically, a common way to mark the ownership of a book has been to stick in a printed image or words, usually on the pastedown of the front board. These take two main forms: the bookplate and the book label. The former is often (though not always) heraldic in nature, and often engraved, while the latter is smaller, simpler and tends to use printed type exclusively. Most libraries can offer a selection of both, and the Wohl Library is no exception. For example, if you look inside any of the ten volumes of the Catalogue des actes de François Ier (EF.442/Fra) you will find the book label of French Early Modernist Fleury Vindry (1869?-1925). Above his name is the familiar latin ‘Ex Libris’ indicating that this item is from the collection of the named individual. These volumes are also labelled on their spines with numbers, indicating their original shelf marks before these arrived in our collections.

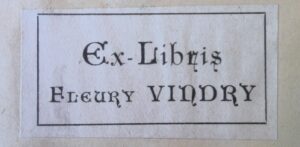

Spines of the Catalogue des actes de François Ier (EF.422/Fra) including original shelf mark designation.

Book plates are more elaborate affairs, historically including heraldry and used by aristocrats, clergy and monarchs to identify their collections. They have a whole language and style of their own, which must be learned if you have any hope of identifying them. Heraldry uses its own archaic vocabulary, describing colours (tinctures), symbols (charges), arms and crests using a hybrid of English and Norman French. To describe the design of a coat of arms is to ‘emblazon’ it, and once you know the blazon, you can match it to an owner. Below is just one example of a bookplate in

the IHR collections. It is the plate of Sir Charles Cayzer, Bartonet of Gartmore, found in Public Characters, 1798-1799 (B.201/Pub). Using heraldic vocabulary, the plate can be described thusly:

Arms: Party chevron Azure and Argent in chief two Fleur-de-lys Or and in base an Ancient Ship with three masts, Sails furled Sable, Colours flying Gules, a Chief invected of the third thereon three Estoiles of the first

Crest: A Sea-lion erect proper holding in his dexter paw a Fleur-de-lys and supporting with his sinister an Estoile both Or

Motto: Caute Sed Impavide (Cautiously but fearlessly)

Though the mixture of English, Norman and Latin can be a little daunting, once you know your chevrons from your saltires it is just a case of writing out the blazon and then taking it to the reference works. Sometimes it can be easier than that. In this case, we have a motto, a crest and a name to help us along.

The coat of arms of William Carr Beresford tooled into the binding of ‘The despatches of the Marquess Wellesley’.

Heraldry manifests not only in bookplates, but also on bindings. Such is the case with our second edition copy of the first volume from The despatches, minutes, and correspondence, of the Marquess Wellesley (CLC.3132/Wel). The book has been purposely rebound in tan leather and tooled with several decorative markings on the front and backboards and the spine. Of most interest is the heraldic arms that have been tooled into the boards of the binding. The blazon of the arms is ‘Arms Per fess ermine and azure a pale counterchanged three dragons heads erased’. Further included in a garter around the arms which reads ‘Tria Juncia in Uno’; the motto of the Order of the Bath. With this altogether, a little research will take us to only one possible owner: William Carr Beresford, first Viscount of Beresford (1768-1854). This book would have been significant to Beresford, not least because he served as Marshal General of the Portuguese Army under Wellington, and later served as Master-General of the Ordnance in 1828 in Wellington’s first ministry. Perhaps this personal connection to Wellesley is what encouraged Beresford to have this book bound so distinctly. We are given more provenance information regarding the binding when we turn to the end pages and find the very discreet ink stamp that reads, ‘Bound by C Lewis’. One might at first think this is the prominent English bookbinder Charles Lewis, but seeing as Lewis died two years prior to the publication of this second edition, we must assume it was another.

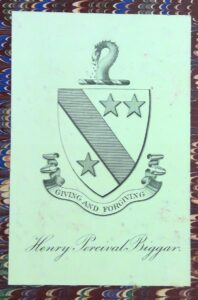

The bookplate of Canadian historian and donor, H.P. Biggar.

A final, and more modern, example of heraldry can be found in Murphy’s, The Voyage of Verrazzano (CG.173/Ver/Mur). On first inspection of the pastedown, one will find the uniform donation plate which was used by the IHR. It reads, quite plainly and clearly, “Presented to the Institute of Historical Research by The Canadian Lectureship Fund Committee Thro. Dr. H.P. Biggar”. Already this plate gives a great deal of information about how the book came to be on the shelves. However, peel away the 20th Century plate (carefully!) and beneath you will find another, older plate. This is the plate of Henry Percival Biggar, the donor himself. It is a simple shield, emblazoned with ‘argent, a bend azure between three estoiles gules’. Atop the shield is a crest with the long necked head of a bird, and below is a motto: ‘Giving and Forgiving’. This example nicely illustrates how plates have been used in books from the nineteenth century up to the modern day. Their design differs from their early modern predecessors: the design is plain, the shield is simple, coronets and helms are dispensed of and mottos written in plain English. Yet, the tradition endures and these plates continue to provide a fascinating insight into the ownership of books.

Inscriptions and Stamps

More so than specially printed labels and plates, inscriptions are a very common marking of provenance in books. Though this type of evidence comes with its own palaeographical challenges, it can provide the bibliographer with richer details beyond basic identification.

To illustrate the value of inscriptions, we need only return our attention to The voyage of Verrazzano (CG.173/Ver/Mur) wherein we found the ‘hidden’ bookplate belonging to H.P. Biggar. If one were to venture beyond the pastedown and enter the end pages, you might come across a handwritten inscriptions which reads:

Sir de Guerra y Orbe

with the compliments of the author,

Hen:[ry] C. Murphy

Brooklyn Jan[uar]y. 17. 1876.

![An inscription which reads, “Sir de Guerra y Orbe with the compliments of the author, Hen:[ry] C. Murphy Brooklyn Jan[uar]y. 17. 1876”](https://blog.history.ac.uk/files/2021/07/WIN_20210702_17_45_47_Pro-1024x571.jpg)

An inscription written by the author to the original recipient of the book, Spanish antiquarian Aureliano Fernández-Guerra y Orbe.

Other inscriptions are more basic. Writing a name near the front of a book has been a common practice for centuries, by individuals from all backgrounds. These can be names of institutions, but more likely are the names of individuals. For example, the inscription of ‘Mary K.J. Hervey’, in the 1893 reprint of Ickworth survey boocke (BCC.8199/Ick). The 17th Century work surveys ‘all the [farms], tenements, lands…within the [town] and parish of Ickworth in…Suffolk, being the estate of John Hervey”. John Hervey (1616-1679/80) was an aristocrat, gentleman of the privy council and treasurer to Queen Catherine of Braganza who inherited Ickworth from his father. The shared surname between the subject matter and the owner raises eyebrows. Might this be a Victorian descendant of the Herveys of Ickworth? The family name did carry on into the 1800s, and there were Mary Herveys in the family, not least the ‘celebrated beauty’ engraved by James Heath. Could this be a descent of the Hervey line? Or perhaps an unrelated Hervey? Only further provenance research can say with certainty.

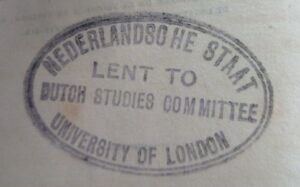

Stamp found in ‘Résumé des négociations’, (ENB.552/Spi).

Where names haven’t been written, they are sometimes stamped. This is usually (though not always) more commonly an institutional practice, rather than an individual one. Most libraries have made use of identifiable ink stamps since the late nineteenth century. We have our own such stamps at the IHR, and mark every book with them – once on the title page verso, once on the text block fore edge (and a couple more on maps, fold-outs, and anything else that might get nicked). Unlike bookplates and bindings, these stamps are not for posterity, but security. If a rare or valuable book is stolen, it can often be identified by its stamp. In addition, customised versions of ink stamps can be used to mark loans or other types of materials. Such an instance can be found in the Résumé des négociations, qui accompagnèrent la révolution des Pays-Bas autrichiens (ENB.552/Spi) which is one of many books that, according to their stamp, were lent to the University of London Dutch Studies Committee by the Dutch State. One can only assume the Dutch government never asked for them back…

Defacement and Custodianship

Historical research can often be a frustrating affair. Sometimes a long trip to a hard-to-find records office might result in nothing at all. The same can be said for books. Most of the library collections are lacking any distinctive markings which might betray their provenance. Some of this is perhaps due to careful owners, who kept their books in pristine condition. However, there are other instances of provenance being altered or removed from books – sometimes by accident, other times deliberately.

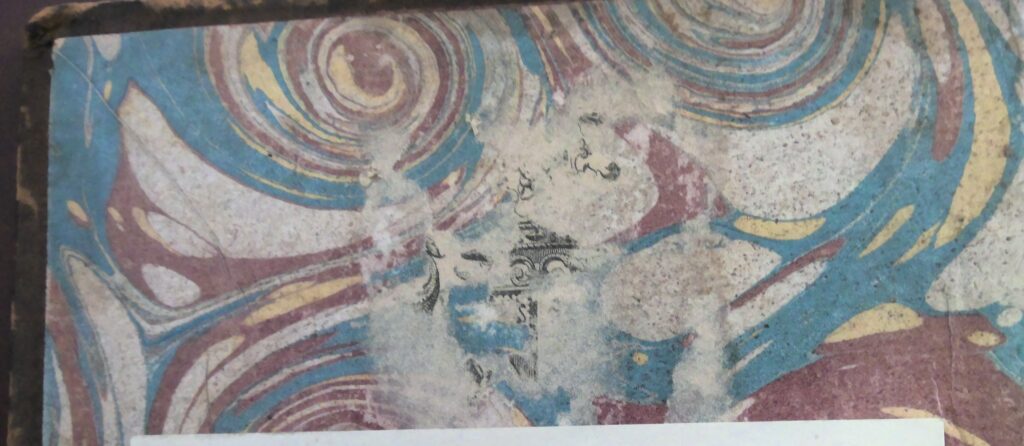

One such instance can be found in a 1769 edition of Descamps’, Voyage pittoresque de la Flandre et du Brabant, (END.316/Des). On the marbled pastedown of the frontboard, you will find the residual mark of what was once a bookplate belonging to a previous owner. Why it was removed, we can’t be sure. Perhaps a later owner wanted to remove signs of any former ownership, or perhaps a neurotic librarian tore it out in a fit of rage (a state of mania I can sympathise with). Regardless, now all that remains are a few fragments of the upper shield, the torse and the crest. There is not enough of any section to identify much of research value.

The remains of a bookplate which has been torn out of ‘Voyage pittoresque de la Flandre et du Brabant’, ENB.316/Des.

As librarians and custodians of books, this raises a very important question: what is our duty to preserve provenance evidence? Librarians are keen to keep their collections well organised and in good condition, and anyone found defacing a library book will face their wrath. Yet, sometimes a damaged, defaced or otherwise marked book can hold enormous historical value. Though our books are primarily coveted for their contents, their materiality cannot be wholly neglected, especially in the case of rare or unique items. Yet, with limited resources and time, librarians must take a practical and sensible approach to how they can assist in provenance research. Not every word of marginalia can be catalogued, and not every blazon deciphered, but some thought should be spared for the preservation of the book as historical evidence.

Final Thoughts

What general observations can be made from this ‘spot check’ into provenance at the Wohl Library? Well, perhaps unsurprisingly, it reveals that many of our books came from the collections of working historians, antiquarians and their respective institutions. For the most part, these items have not been kept on shelves, only for their spines to be admired from across the drawing room. They have been, and continue to be, practical objects in the pursuit of historical research. From its foundation, the Institute has seen itself as a ‘laboratory’ for historians. If we follow that analogy, then these books are the tools, the practical instruments, which historians use to perform their work. While provenance research spends a great deal of time looking at the spines, the bindings and the general materiality of the book, we mustn’t forget the crucial thing; that these collections exist not to be fetishized, fussed-over and admired, but rather, they are to be read.

I would like to thank the IHR for providing funding and leave to attend the London Rare Books School course ‘Provenance in Books’ which has provided me with indispensable skills and knowledge. You can learn more about the provenance of our collections on the IHR website.