On Thursday 8 July 2021, the IHR celebrated its 100th birthday, with a day of online celebrations taking us from Australia and South East Asia, to Africa and the Middle East, to Europe and North America. What did we learn about history today and in the future?

The first session in the IHR Centenary celebration, chaired by Dr Diya Gupta, opened with a discussion between Professor Sandra Wilson from Murdoch University, Australia; Professor Shigeru Akita from Osaka University, Japan; Professor Heasim Sul from Yonsei University, South Korea; and Professor Tanika Sarkar from Jawaharlal Nehru University, India. The themes they drew upon were wide-ranging and thought-provoking. They considered the drawbacks involved in the narrowing of history to simply mean memorialisation, recent initiatives integrating Japanese history with more global approaches, the rise of neo-nationalism in Korea with a declining interest in global and Western history, and political pressures that have made researching and teaching history perilous in India. It was fascinating to uncover the different ways by which national structures had shaped and often constrained the discipline in the four countries.

The conversation then opened out into opportunities for the future. Sandra Wilson spoke of the crucial role history has to play in public debate, providing us with the recent example of investigations into Australian ‘war crimes’ in Afghanistan, while Shigeru Akita highlighted new possibilities in collaborating with Japanese journalists and school-teachers in broadening the scope of history. Heasim Sul analysed the difficulties history scholars have in finding jobs and sustaining their livelihoods, which makes the future of historical research highly precarious. Tanika Sarkar spoke powerfully about the need to popularise ‘real history, responsible history’ and to open up opportunities for early-career scholars from India and the Global South to undertake ambitious research projects, cutting across conventional boundaries. Perhaps this is where the IHR has a significant role to play. The session ended on a resounding note of solidarity for the practice of history itself and all those historians who find themselves endangered because of the work they undertake.

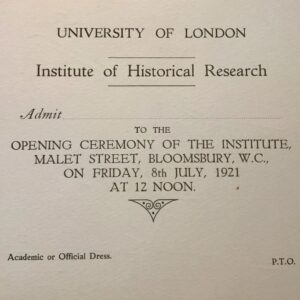

IHR Opening Ceremony Invite

The second session, chaired by Professor Mary Vincent, gave eloquent testimony of the innovation and creativity that currently characterises African history. In a fascinating and truly informative discussion, Professor Vivian Bickford-Smith, Dr Eva Namusoke, Dr Cécile Feza Bushidi, Dr Felix Oludare Ajiola and Professor Amina Elbendary spoke of both the challenges facing historians in the region and how they are responding to them. With academic resources prohibitively expensive even for university libraries, researchers are using social media platforms such as Twitter to make their findings available, a move outside the traditional academy that also allows more marginalised stories to be told. African history is no longer dominated by ‘big men’, in Eva Namusoke’s words, which could make the discipline feel far removed from the population: these reinvigorated tales have new subjects and different narrators. Challenges remain, some of which are familiar to many of us, such as the designation of humanities subjects as a luxury. Yet, as Alina Elbendary pointed out, the consequences are sharper when resources are scarce. Felix Ajiola spoke powerfully of the need to secure history for the future, by pressing for archive policies that allow access, conservation, and the preservation of records, threatened in some countries by corruption and commodification.

There was general agreement of a shift away from Eurocentric assumptions and old national paradigms though Vivian Bickford-Smith pointed to a continuing lack of transnational or comparative studies. Cécile Feza Bushidi, though, spoke of the black diaspora and how diasporic histories create new understandings of place and also acknowledge complex personal histories. Decolonising must include celebrating black agency and several of our speakers commented on the difference between local written history and that produced by those outside. The final part of the discussion focused on the IHR, and how we can support African historians and African history, for the future as well as for now. There is a need for time and space for research, perhaps through targeted fellowships, as well as partnering with African institutions in research bids, digitisation, and programmes of co-operation across the continent.

The final session of the day, chaired by Professor Catherine Clarke, brought together a distinguished panel of speakers from Europe and North America: Professor Bernhard Rieger, Professor of European History at the Institute for History, Leiden University; Professor Amanda Herbert, Associated Director at the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington DC (board member of the American Friends of the IHR); Professor Newton Key, Distinguished History Professor Emeritus at Eastern Illinois University (and Vice-President of the American Friends of the IHR); Professor Douglas Peers, Dean Emeritus for History at the University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada (who has been involved in the creation of the Canadian Friends of the IHR); and Professor Karin Wulf, Executive Director of the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture and Professor of History at William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia.

The opening video birthday message from Sir David Cannadine reminded us of Pollard’s vision for the IHR as a laboratory for experimental and innovative ways of doing history, something picked up in the discussion as speakers considered what this mission might mean in the wake of Covid-19 and the move to new, online or hybrid modes of teaching, research and engagement. Much of the discussion focused on fraught political contexts and the hostilities or challenges facing history and historians today. Panellists unpicked that false divide between ‘historians’ and ‘the public, discussing ways of communicating across silos and meeting people where they are; engaging with the immense popularity of history and its ‘ordinariness’ today; and moving from ‘public-facing’ research to genuine collaboration and co-production with different kinds of communities and specialists. Audience members shared some great case-studies and examples of good practice in the Chat. The discussion also focused on who was not present on the panel or in the room: the historians absent or less visible on the evening’s platform. The panel discussed the importance of building greater diversity and inclusion across history in all its forms, and the implications of taking seriously the message ‘nothing about me without me’. Speakers shared exciting aspirations for greater international collaboration and possible roles for the IHR here.

After a final birthday message from IHR Centenary Patron Professor Shahidha Bari – which again foregrounded the role of history in telling stories and making identities – we were joined by a very special guest: Professor Claire Langhamer, incoming Director of the IHR (due to join the Institute in October 2021). Claire’s closing words made a powerful case for history today and into the future, reflecting her own deep commitment to diversity, collaboration and inclusion in everything we do. Her vision of the IHR at the centre of a ‘playful, creative, experimental’ community of historians ended the day on a note of inspiration, looking forward to the possibilities of the Institute’s next hundred years.

Watch recordings of all the events discussed in this report in the IHR Events Archive.

All IHR Patron Birthday Messages are also now available to watch.

Diya Gupta, Mary Vincent and Catherine Clarke