In this post Dr Rosalind Johnson introduces her chapter in Church and People in Interregnum Britain, published by University of London Press on 23 June.

Edited by Dr Fiona McCall, the book provides a comprehensive account of every-day life, society and religion in the interregnum period (1645-1660) under Oliver Cromwell.

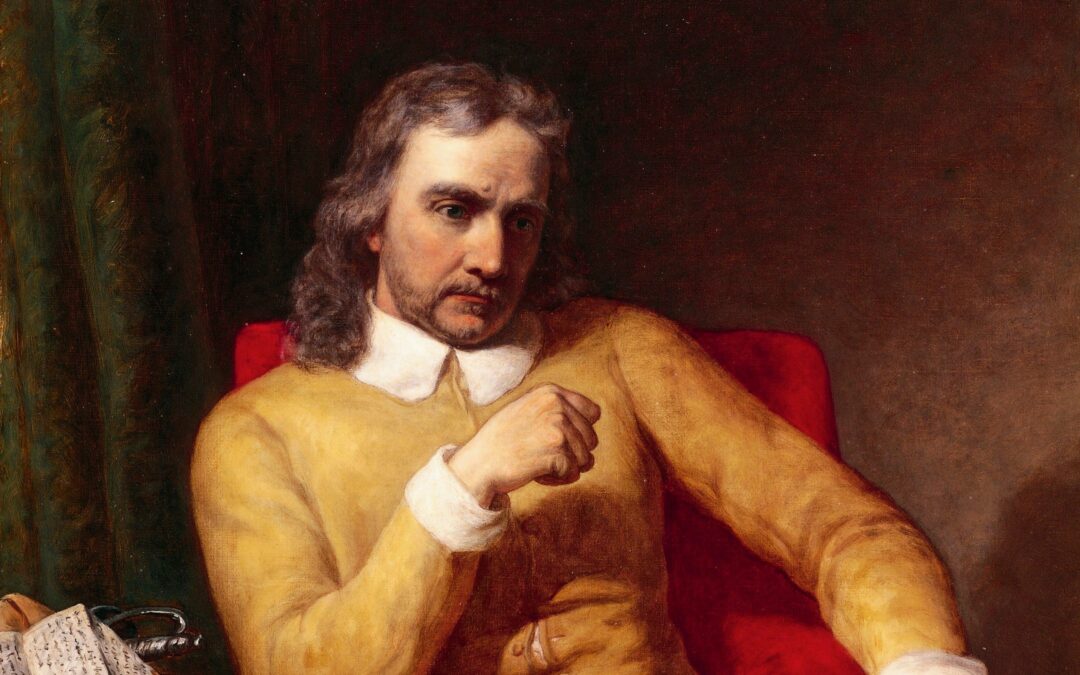

On Christmas Day 1657 the diarist John Evelyn and his wife Mary attended a communion service in a private chapel in a London house. To the surprise of Evelyn and the rest of the congregation, they found themselves surrounded by soldiers menacing them with their muskets. The soldiers detained all those they found at the service; Evelyn was held and questioned, but the soldiers eventually let him go.

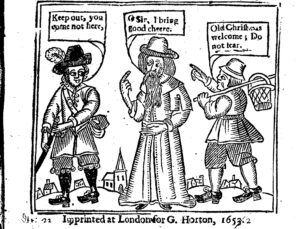

By taking part in a celebration of holy communion at Christmas time, Evelyn and his wife knew they were breaking the law. In 1645 the Anglican Book of Common Prayer had been replaced by the Directory of Public Worship, a book which was largely a set of directions for public worship, rather than a formal liturgy in the manner of the prayer book. The Directory specified that communion services could be held, when and how being up to the minister and congregation. But Christmas, Easter, Whitsun and other religious festivals, not being authorised as such in the Bible, were not to be celebrated.

By taking part in a celebration of holy communion at Christmas time, Evelyn and his wife knew they were breaking the law. In 1645 the Anglican Book of Common Prayer had been replaced by the Directory of Public Worship, a book which was largely a set of directions for public worship, rather than a formal liturgy in the manner of the prayer book. The Directory specified that communion services could be held, when and how being up to the minister and congregation. But Christmas, Easter, Whitsun and other religious festivals, not being authorised as such in the Bible, were not to be celebrated.

The Directory was not the only attempt in the 1640s and 1650s to ban major festivals. Several attempts were made by Parliament to legislate against secular and religious celebrations. The parliamentary ordinance of June 1647 specifically banned any religious or secular celebrations of Christmas, Easter, Whitsun and other religious festivals (though it did allow the second Tuesday in each month as a secular holiday for scholars, servants and apprentices).

John Evelyn and his wife were far from alone in taking part in an act of worship at Christmas. They were only unlucky in having been caught. Studies by Valerie Hitchman, Ronald Hutton, John Morrill and others have found that many churches were celebrating Christmas, Easter, Whitsun and other religious festivals between 1645 and 1660. The evidence is hiding in plain sight; churchwardens recorded in their accounts the purchase of bread and wine for the communion, sometimes adding that it had been purchased for a specific festival.

In the parish of Chawton in Hampshire (a village more famous as the later residence of Jane Austen) the churchwardens recorded buying bread and wine for Christmas on at least seven occasions in the 1650s, and on eight occasions for communion services on Palm Sunday and Easter Sunday. In the small market town of Wilton near Salisbury in Wiltshire communion services took place on Palm Sunday and Easter Sunday on several occasions in the 1650s, though festal services at Christmas and Whitsun seem to have ceased by the end of the 1640s.

The churchwardens did not only buy bread and wine for festal communions. The Wilton churchwardens paid for cleaning the church at Christmas 1646, as did the churchwardens of St Thomas, Salisbury, in their accounts for 1655-6. The St Thomas accounts also recorded ‘dressing’ or decorating the church. The churchwardens did not specify how the church was decorated, but it is likely that rosemary, bay and holly, being evergreens, would have been used as Christmas decorations. The churchwardens of St John the Baptist parish in Bristol bought rosemary, bay and holly on several occasions in the 1650s, probably for this purpose.

Rogation Sunday and Rogationtide (the fifth Sunday after Easter, and the three days following) are less well-known today, but were of more importance in the early modern period. Traditionally it was the occasion when people processed around the parish boundaries, sometimes followed by feasting. As the parish administered poor relief, it was important to know exactly where the parish boundaries, and thus the parish responsibilities, lay, though Rogationtide perambulations did not necessarily occur in all parishes even before the Civil Wars. As a religious festival it was implicitly banned by the June 1647 ordinance, but there are references to perambulations taking place in some parishes after this date. This suggests that the secular aspects of the practice were tolerated during the Interregnum – it would have been difficult to be discreet about a public procession.

Several Bristol parishes held Rogationtide perambulations. At St Mary Redcliffe the perambulation day of 1654 concluded with a dinner, and in Temple parish expenses in the 1650s include payments to the ringers, and dinner at the Lamb inn. The parish of St John the Baptist celebrated with a dinner, and also with cakes, which in 1657 were specifically recorded as having been given to the children of the parish.

The true extent of religious celebrations in this period, whether secular or religious, will never be known. Churchwardens’ accounts, the evidence for many religious celebrations, do not survive for most parishes. But those cases that came to the attention of the authorities were surely just a fraction of those that actually took place.

But why did churchwardens record that they were buying bread and wine for festal communion services, when they knew it was against the law? Why not simply record the purchase of bread and wine, without adding the detail of the festival? Kevin Sharpe suggested that the most complete records were kept by the most diligent churchwardens, whose inclination to order led them to record such particulars. It may also be that, in a period of uncertainty, the act of writing was a way of exercising control. Or it was a form of quiet rebellion; a peaceful demonstration of non-compliance. Furthermore, the minister and the parishioners were necessarily complicit in the churchwardens’ actions. This suggests a toleration in many parishes, and possible compromises between those of different religious perspectives. Historians often write about conflict; harmonious relationships have left less trace in the historical record.

Rosalind Johnson is a visiting research fellow in the Department of History at the University of Winchester. She is a contributor to the volume Church and People in Interregnum Britain, ed. Fiona McCall, published by the University of London Press in 2021.