By Kathryn Dyt

Environment & History, essay no. 11

For the eleventh essay in our ‘Environment & History’ series, Dr Kathryn Dyt draws our attention to the importance of emotive responses to environmental disasters by political leaders. Discussing the Nguyen dynasty’s emotive responses to meterologically induced destruction and famine in nineteenth-century Vietnam, Dyt not only recognises the cultural difference in attitudes towards nature, but the political potential of emotional appeals. Noting the growing realisation in western culture that facts alone have not resulted in action against climate change, this essay encourages us to consider embracing more empathetic political dialogue.

The next essay in the ‘Environment & History’ series will be published Wednesday 14 April 2021 with ‘The battle for land “in the national interest” during Britain’s Second World War‘.

“We must …. always accept that we must be humble in the face of nature”. In his highly anticipated “roadmap out of lockdown” speech on 22 February 2021, the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson urged people to follow a prudent approach to the easing of restrictions put in place to curb the COVID-19 pandemic. In so doing, he emphasised human vulnerability in the face of the deadly virus, which has already claimed more than 2.5 million lives worldwide. Media responses to the speech noted the uncharacteristically cautious and empathetic tone of his address. Gone was the usual emphasis on the economic recovery. In its place was an exhortation for people to come together to ensure the safe, steady lifting of “restrictions that have separated families and loved ones for too long.” The morning after his address, BBC Radio 4’s “Woman’s Hour” headlined with the phrase, “forceful leadership out, caring, more empathetic leadership is in”.

While being empathetic may seem at odds with Boris Johnson’s usual buccaneering style of leadership, the harnessing of emotion in response to natural crises is nothing new. Epidemics and other natural disasters, which have a shattering impact on communities, have often been met with emotional reactions from leaders.

My research on royal governance during the Nguyen dynasty in nineteenth century Vietnam shows that a high value was placed on rulers displaying emotion in response to environmental crises. Conveying empathy and being emotionally responsive – both to the environment and to people suffering the brunt of disasters – was an important facet of Nguyen kingship and dynastic authority. Of course, a nineteenth century Vietnamese king and the current Prime Minister of the UK are worlds apart. But ideas about affective kingship and the natural world in Nguyen Vietnam are good to think with; they encourage critical reflection on human-nature relations and the importance of emotion for political leadership in our current age of environmental crises.

The timely rain had brought some joy,

But the collapse of the dikes added to my worries.

Benefit and harm are not in balance,

Sorrow and delight are beyond my will,

Anxiety derives from my allotted fate.

Written by King Tu Duc who ruled Vietnam from 1847 to 1883, these lines convey the king’s anxiety and sorrow about the suffering of his subjects. In the poem, he pins his feelings to a shifting meteorological landscape that is beyond his control. The poem was prompted by droughts and floods that were affecting different parts of the kingdom, leading to famine and disease, including cholera epidemics.

Portraits and costumes of the emperor (Tu Duc) and his ministers. Drawing by Émile Théodose Thérond in Le Tour Du Monde, Volume 1, 1860, p. 49.

The four Nguyen kings who reigned from 1802 to 1883 prior to French colonial rule – Gia Long (r. 1802-1820), Minh Mang (r. 1820-1841), Thieu Tri (r. 1841-1847) and Tu Duc (r. 1848-1883) – often responded emotionally to events in the natural world. Primary sources from the time recount how kings trembled and wept inconsolably and how they were unable to eat or sleep properly due to the distress brought about by natural disasters. The emotionally charged poems that Nguyen kings wrote during times of crisis were distributed widely throughout the country to let people know about the monarch’s feelings.

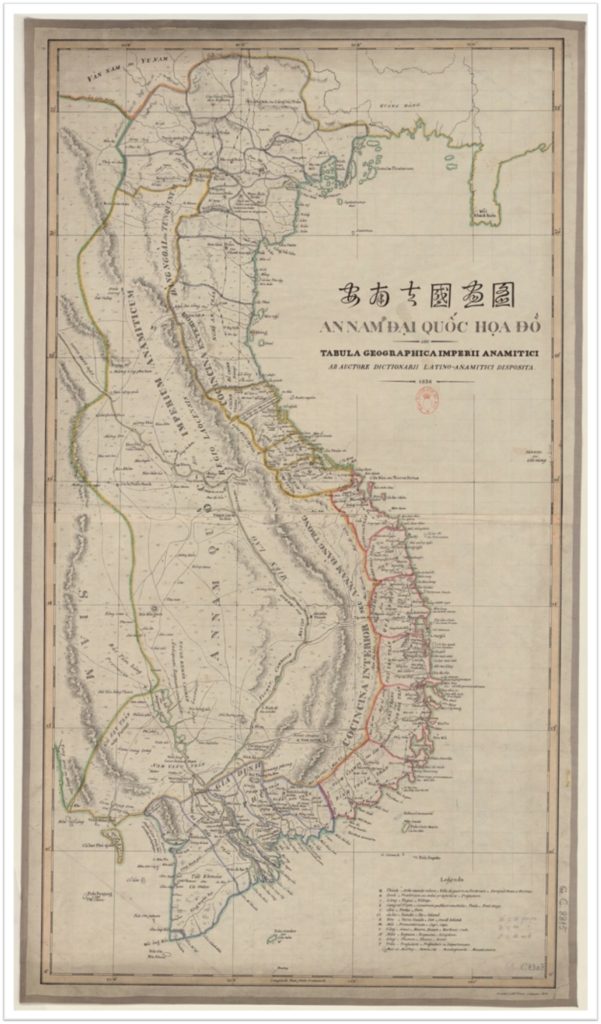

Emerging after more than two centuries of fraught division between north and south, the Nguyen dynasty was the first to rule over a unified Vietnam, stretching about 1,650kms from the northern mountainous regions, through the location of the Nguyen court in the central of city of Hue, to the southern Mekong delta. The nineteenth century Vietnamese kingdom spanned a varied landscape encompassing multiple climatic worlds and was blighted by frequent natural disasters including typhoons, floods, droughts and epidemics.

Jean-Louis Taberd, ‘Map of Vietnam’, printed in Dictionarium Latino-Annamiticum completum et Novo Ordine Dispositum (1838).

A central argument of my research on nineteenth century Vietnam is that Nguyen rule was inherently bound up with this capricious environmental context and affective responses to the natural world. Emotions were so central to politics because the environment was itself seen as an emotional terrain. Simply put, the Nguyen conceptualised the environment as an alive, embodied, emotional entity, which could both think and feel. Like human beings, it was understood to be animated with an “essential life force” or “khi” in Vietnamese. This life force pulsed underground through “earth veins” and it drifted through the atmosphere in the form of wind and rain. The “khi” of the environment interacted with the “khi” of human beings in a reciprocal resonance. English terms like “environment” and “nature” – denoting, among other things, a realm that exists separately from human experience – have no direct equivalents in the nineteenth century Vietnamese past. In Nguyen Vietnam, there was no strict divide between nature and culture, no concept of a meteorological realm detached from humanity. Living within an all-encompassing “weather-world”, to use Tim Ingold’s term, humans and nature were causally connected.

Accordingly, it was thought that natural disasters and bad weather could be remedied by affective exchange between people and the weather-world. The emotions of the king were deemed especially powerful in this regard. By expressing heartfelt sorrow and angst in their poems, Vietnamese kings tried to turn the meteorological tide and restore climatic balance. Ritual was another arena where the king’s sentiments could have a profoundly transformative effect and the key to unlocking ritual efficacy was sincerity. The king’s feelings were important even when they could not bring about a change in the environment. During times of natural disaster, people looked to the king to empathise with their anguish and suffering. Kings acted as a kind of lightening rod to channel, absorb and make sense of the outpourings of emotion that coursed through the kingdom.

It should be said that nineteenth century Vietnamese kings are not conventionally thought of as emotional beings. Past kings and leaders rarely are. One reason for this is the tendency to view historical leaders from the vantage point of the modern bureaucratic state, which prioritises models of rational rule. Rationality as the basis of reasoned, intelligent decision-making has been championed since the Enlightenment, and emotionality, devoid of intellect, is its antithesis. Just as traditional approaches to the writing of history have partitioned off “natural” and “human” pasts, historical accounts of kingship and royal governance often separate out emotion from politics.

This rational/emotional dichotomy continues to play out in present-day environmental politics. Although the health crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic has led to politicians conveying empathy, the longer-running, but equally urgent, climate crisis of global warming has been met with a greater degree of emotional restraint from some leaders, including Boris Johnson. In his opening remarks at the Climate Ambition Summit on 12 December 2020, the Prime Minister put faith in “scientific advances” to “save the planet”, and he quipped that “we in the UK” are not “hair shirt-wearing, tree-hugging, mung bean-munching eco freaks.” By this, he infers that the British are not fanatical or overly emotional about the environment. Love of trees will not cloud scientific judgement when it comes to climate action.

Yet there is an increasing realisation amongst the scientific community that making the rational, scientific case is not in itself sufficient to convince people who remain sceptical about the human causes of climate change or to galvanise the political will that is required to move to a carbon-neutral world. Facts alone are inadequate in motivating people and leaders to act. Undoubtedly, strong emotions have energised forms of direct action like the Extinction Rebellion protests and the global “school strike for climate” inspired by Greta Thunberg.

In the nineteenth century court of the Nguyen dynasty, it would have been unimaginable to be emotionally detached from the environment, in part because the landscape was understood to be full of sentiment. Royal rule required responding to and mediating these emotional flows through sincere behaviour and ritual practice. Today we might discount the notion that rituals are efficacious in the natural world or that human beings can resonate with an emotional environment. And yet, in the current pandemic and climate emergency the idea of how nature “treats us” is more at play than ever before. In this sense, the problems faced by nineteenth century Vietnamese kings – of how to connect with nature and utilise emotion effectively – are ones we all share.

Featured image: La Pán Tẩn Agriculture, Vietnam. Photo by Văn Ngọc Tăng.

***

Dr Kathryn Dyt is Past and Present Fellow 2019-21 at the IHR, researching the Nguyen Dynasty in nineteenth century Vietnam through an environmental lens. Her thesis, completed at the Australian National University, was awarded the 2018 ASAA Prize for the Best Thesis in Asian Studies. She has published her research in the Journal of Vietnamese Studies and in the edited book Natural Hazards and Peoples in the Indian Ocean World: Bordering on Danger. Kathryn is currently completing her monograph, The Nguyen Weather-World and the Nature of Kingship in Nineteenth-Century Vietnam.