By Harriet Mercer

Environment & History, essay no. 10

In the tenth article in our ‘Environment & History’ series, Dr Harriet Mercer discusses how the history of knowledge production can help us understand whose voices are more privileged in the discussion of climate change, and why.

Drawing on her postgraduate research, which focused on late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century Australia, Mercer adds to arguments raised in Sharla Chittick’s earlier post (‘Environment & History’ no. 4) about the value of indigenous knowledge. In ‘Colonialism’s Climatic Legacies’, Harriet Mercer urges us to appreciate the value of that knowledge, not only for histories of the environment or climate, but for solving our current environmental crises.

The next essay in the ‘Environment & History’ series, ‘Emotional Leadership and Environmental Crises: A View from Nineteenth Century Vietnam’ will be released on Wednesday 7 April.

Cultural advice: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this article contains the name of a deceased person.

IPCC REPORTS AND INDIGENOUS CLIMATE KNOWLEDGE

The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is widely acknowledged as the leading international organisation shaping climate change knowledge across the world.[1] Every five to seven years, the IPCC issues reports which provide assessments about the causes and impacts of climate change as well as potential mitigation and adaptation strategies. The IPCC does not conduct its own research in order to produce the reports. Instead, teams of expert authors assess vast amounts of peer-reviewed literature as well as government and industry reports on topics related to climate change. To date, there have been five IPCC reports and the sixth is due to be published this year.

One of the main critiques that have been levelled at the existing IPCC reports is the lack of incorporation of indigenous peoples’ perspectives and knowledge about climate. The critique has been aimed in particular at the part of the IPCC reports which focus on impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Critics have pointed to the fact that although numerous indigenous peoples occupy regions that are amongst those most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, their understandings of climate have not been included in the IPCC’s assessments. The earliest reports of the IPCC contained only a handful of references to Indigenous peoples and their knowledge.

Acknowledging this gap, the IPCC made a concerted effort to increase the amount of indigenous knowledge in the content of its last two reports. The fourth IPCC report of 2007 included an increase in indigenous content, especially in the regional chapters of the report. A Nature Climate Change study of the last IPCC report of 2014 showed that there was a further 60% increase in the occurrence of indigenous relevant keywords. The same study, however, found that despite the increased reference to indigenous peoples and their knowledge, ‘the coverage was general in scope and limited in length’.[2] The study also found that the report often treated indigenous knowledge ‘as a static form of knowledge that is being undermined or made irrelevant by climate change’.[3]

Driving through the open roads of New South Wales, Australia. Photo by Tarryn Myburgh.

THE ROLE OF CLIMATE HISTORY

Why has indigenous knowledge been treated as a static form of knowledge? And why has it been treated as separate or excluded from the climate knowledge reporting of governmental and international organisations such as the IPCC? These are the kind of questions that history and in particular climate history can help to answer. The study of history tells us that it is important to not only identify the gaps in the IPCC reports; it is also important to understand how those gaps and exclusions came about in the first place. The study of climate history helps to reveal the specific historical circumstances that produced those gaps.

Climate history is a broad church. There are climate historians, often referred to as historical climatologists, who use historical documents to help reconstruct past climatic events and episodes. Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, for example, used grape harvest dates to help him reconstruct centuries of seasonal temperature variations in Europe. Another type of climate historian is those who use the reconstructions of historical climatologists as well as the reconstructions created by paleoclimatologists to study the impact of climate on past societies. Consider, for instance, the work of historian Dagomar Degroot who examined the impact of the Little Ice Age on the sixteenth and seventeenth century Dutch Republic including the impact of changed wind conditions on the maritime power of the Republic.

There are also climate historians who study past understandings of climate. This type of climate history has been reinvigorated recently by historians such as Deborah Coen who has shown that the makeup of the Habsburg Empire proved conducive to the creation of dynamic climatology and Sarah Dry who has shown how studying water in its different forms was critical to the discovery of global warming and climate change. A new research project at the University of Cambridge is also pursuing these themes through its investigation of the relationship between the human impact on the climate system and efforts to understand that system. In different ways, all these types of climate history can help to illuminate the complex processes that have shaped the way different types of knowledge have been treated over time.

THE AUSTRALIAN CASE

My own research merges the latter two types of climate history. In my PhD thesis, I studied the relationship between the experience of past climatic variability and efforts to understand that variability. I focused on the early part of the European colonisation of Australia, from the late eighteenth to the mid nineteenth century. It was in this period that Europeans worked to establish a settler colony in south eastern Australia. And it was in this period that the new arrivals experienced highly variable rainfall and temperature patterns, with some of that variability arising from shifts between the El Niño and La Nina phases of the El Niño Southern Oscillation that brews over the tropical Pacific.

I show that in their effort to understand Australia’s climate, some colonists sought out the climate knowledge of Aboriginal Australians. I also show that some Aboriginal Australians were willing to share their expertise. The surveyor Thomas Mitchell, for instance, relied on the knowledge of Yuranigh from Wiradjuri country to help him interpret the hydraulic history of inland eastern Australia. How severe were the signs of recent floods compared to previous ones? How frequent were flood events in the region? These were some of the questions to which colonists like Mitchell sought Wiradjuri answers. At the same time, however, I show how colonists grew increasingly wary of Aboriginal peoples’ climatic knowledge because of the challenge that knowledge presented to the settler concept of terra nullius or land belonging to no one.

‘The common idea we [Australians] have is that knowledge about the weather patterns in this country only exists since recordings made by scientists in about the last two centuries. But there are records. For instance, what do we really understand of the rock art? These stories stretch over large areas of land in galleries that are the ancient libraries of this land’, the Waanyi novelist Alexis Wright has observed.[4] With these powerful words, Wright pointed to a tendency in contemporary Australia to dismiss or overlook indigenous climate knowledge. This tendency was not an historical given; an attitude that arrived unanimously with European colonists from the late eighteenth century. Rather, I show in my thesis that the tendency to overlook indigenous ways of knowing the climate was part of a process that took place over time – it was part of the process of settler colonialism and a broader effort to legitimate the settler presence in Australia.

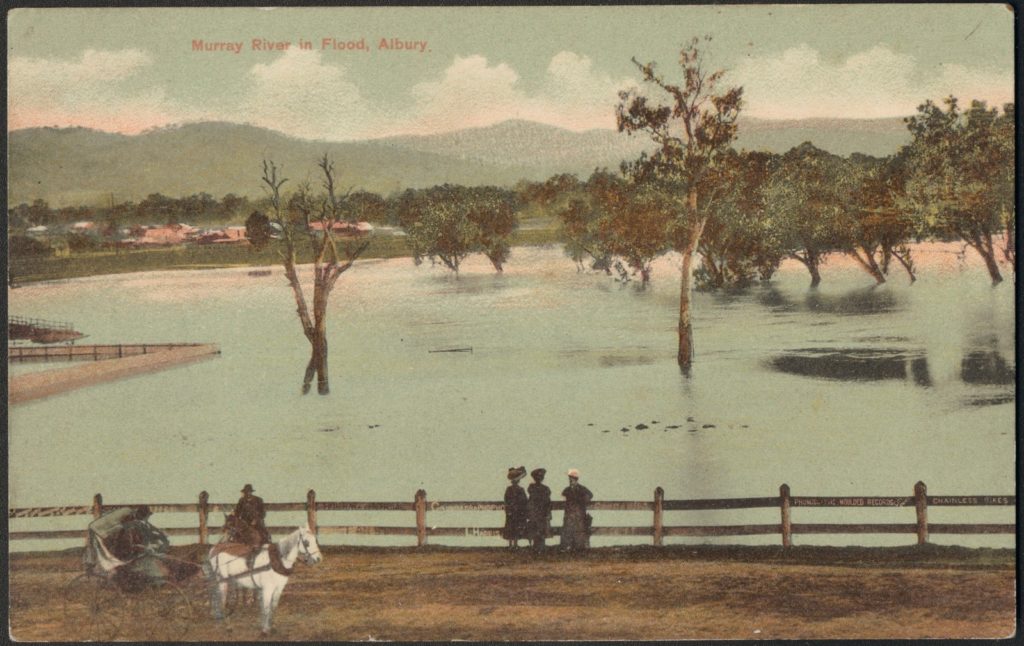

Murray River in Flood, 1908. Postcard: printed, col.; 8.8 x 13.8 cm. approx. State Library of Victoria, H90.140/997.

COLONIALISM’S CLIMATIC LEGACIES

The Nature Climate Change study which analysed the indigenous content of the 2014 IPCC report also provided a list of suggestions for strengthening the IPCC’s future assessment process. One of these suggestions was the inclusion of a specific indigenous focused chapter in the part of the reports dealing with impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Such a chapter would have indigenous scholars, elders and thought-leaders as the lead and contributing authors. Another suggestion was that the IPCC should develop specific guidelines for accessing and incorporating indigenous knowledge systems so that sensitivities around knowledge sharing could be respected.[5] The extent to which these suggestions have been heeded will be revealed this year with the publication of the IPCC’s sixth report.

Whatever additions are made to the next IPCC report can only be strengthened by an historical understanding of the treatment of indigenous knowledge. Adding indigenous knowledge to the reports without understanding the historical treatment of such knowledge is like treating the symptom rather than the cause. Climate history reveals the historical processes and structures of power that produced the gaps in reports such as those produced by the IPCC. It reveals the value systems that have shaped not only the production of knowledge but also the exclusion of certain knowledges. In the Australian case, climate history shows how the contemporary tendency to overlook indigenous climate knowledge is one of the lingering legacies of settler colonialism.

References

[1] Mike Hulme and Martin Mahony, ‘Climate Change: What do we know about the IPCC?’, Progress in Physical Geography vol. 34, no. 4 (2010): 705 – 718.

[2] James D. Ford et. al. ‘Including indigenous knowledge and experience in IPCC assessment reports’, Nature Climate Change vol. 6 (2016): 350.

[3] Ford et. al. ‘Including indigenous knowledge and experience in IPCC assessment reports’, 350.

[4] Alexis Wright, ‘Deep Weather’, Meanjin winter (2011).

[5] Ford et. al. ‘Including indigenous knowledge and experience in IPCC assessment reports’, 351 – 352.

Douglas Nakashima, Jennifer T. Rubis and Igor Krupnik, ‘Indigenous Knowledge for Climate Change Assessment and Adaptation: Introduction’ in Indigenous Knowledge for Climate Change Assessment and Adaptation eds. Douglas Nakashima, Jennifer T. Rubis and Igor Krupnik (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Featured image: Road flooded in Annangrove NSW, Australia. Photo by Phillip Flores.

***

Dr Harriet Mercer has recently completed her DPhil in the Centre for Global History at the University of Oxford. She will be joining the Leverhulme-funded Making Climate History project at the University of Cambridge, as a postdoctoral research assistant in May. Her thesis focused on the history of climate knowledge production in Australia in the nineteenth century, exploring the intersections between climate history and global history.