By Ewan Gibbs

In this post Dr Ewan Gibbs introduces his new book, Coal Country: The Meaning and Memory of Deindustrialization in Postwar Scotland, published by University of London Press on 15 February.

Ewan’s book presents the first book-length account of deindustrialization in the Scottish coalfields. It draws on archival research using records from UK government, the nationalized coal industry and trade unions, as well as the words and memories of former miners, their wives and children that were collected in an extensive oral history project.

Coal Country: The Meaning and Memory of Deindustrialization in Postwar Scotland is the seventh and latest volume in the New Historical Perspectives series from the Royal Historical Society and the Institute of Historical Research.

As for all NHP titles, Ewan’s book is now available free Open Access to download and chapter-by-chapter via the JSTOR OA Books platform. It’s also available in hard and paperback print and as an ebook: now available with a 30% discount (see the end of this blog for details).

One Sunday in September 2019, I boarded a bus that took me the short distance from Glasgow city centre to the North Lanarkshire village of Moodiesburn.

Moodiesburn is at the heart of what had been Scotland’s largest coalfield. A century before, one in three occupied men – around 60,000 in total – worked in Lanarkshire’s coal mines. The county’s last colliery shut in 1983, but Lanarkshire miners continued to cut coal elsewhere in Scotland until the closure of the Longannet drift mines complex in 2002.

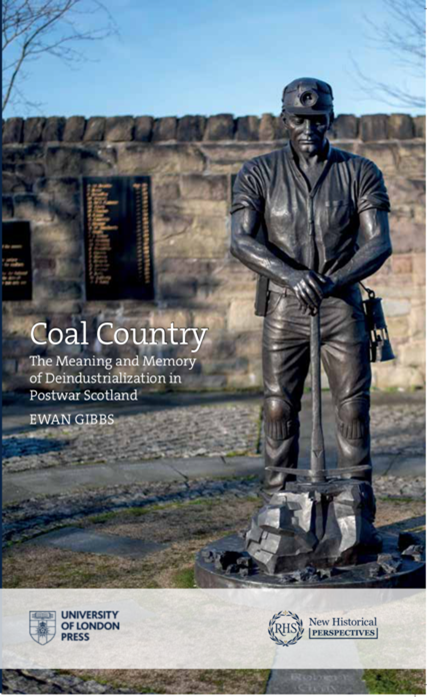

I joined a crowd of around 500 men, women and children at the Pivot Community Centre, adjacent to the Main Street. There were union banners from Scotland and England, a pipe band and even some primary school pupils dressed as miners. Each year since its inception during the 1984-5 miners’ strike, an annual service has been held to commemorate the Auchengeich colliery disaster of 1959, an underground fire which claimed the lives of forty-seven men. At the sixtieth anniversary, a short procession to the Auchengeich Miners Memorial, a statue which depicts a 1950s Lanarkshire miner, was followed by speeches from union leaders, members of the Auchengeich Miners Memorial Committee and local political and religious representatives.

Part of the Auchengeich Miners Memorial, shown on the cover of ‘Coal Country. The Meaning and Memory of Deindustrialization in Postwar Scotland’.

The Auchengeich commemoration recalls the true ‘price of coal’, but it is also a powerful reminder that deindustrialization is a long and painful process that extends long beyond final strikes, lockouts and major closures. The presence of children at the service confirms that industrial culture and identities have outlasted production in Scotland’s coalfields and demonstrates the ongoing intergenerational significance of deindustrialization.

My interest in deindustrialization was piqued when I wrote an undergraduate dissertation on the poll tax non-payment campaign of the late 1980s and early 1990s. The accelerating closure of industrial workplaces during Margaret Thatcher’s premiership produced the young unemployed men who were central to Anti-Poll Tax Federation activism. Deindustrialization also powerfully shaped a political context where class and national consciousness fused in Scotland.

Yet my subsequent coalfields research has revealed the long roots of these changes. The dusty bureaucratic records of the nationalized coal industry became a valuable resource for understanding how these developments could be traced back to the years that immediately followed the Second World War.

Colliery closures were preceded by meetings of Colliery Consultative Committees between management and union representatives. I came across the president of the National Union of Mineworkers Scottish Area, Abe Moffat, cautioning industry officials during the closure of Baton colliery in the Shotts area of eastern Lanarkshire: ‘the Board should realise that they were not discussing a mining engineer’s opinion but the social life of a mining village.’ Baton closed in 1950, just three years after British coal mining was nationalized. Shotts experienced a feeling of abandonment and growing local opposition to closures as pits were shut and miners instructed to move elsewhere in the Scottish coalfields.

A close reading of pit closure records revealed that the Shotts experience was important. After this, miners were generally offered jobs within (extended) travelling distances from their homes, while the Coal Board enticed potential migrants more selectively. Until the 1980s, deindustrialization was managed in a way that largely protected the economic security of individual workers and the integrity of communities.

I recorded coalfield history by boarding buses, trains and boats to interview former miners, their wives, sons and daughters and other former industrial workers from the coalfields.

Some of my respondents had direct memories of the deprivations brought by mass unemployment and class conflict during the interwar period. In 2014, I journeyed to the Isle of Arran and interviewed Jessie Clark. She recalled growing up in the South Lanarkshire village of Douglas Water. Jessie’s father was blacklisted by vindictive coal owners, and she survived by picking coal off bings with her mother before undergoing the oppressive experience of employment as a teenage domestic servant.

In other cases, memories were transmitted from one generation to another. Mick McGahey, the son of Michael McGahey, who was President of the NUMSA from 1967 to 1987, recalled that he had followed in the footsteps of his father and grandfather when he was victimised and lost his job during the 1984-5 miners’ strike after being arrested picketing in Midlothian.

The head of the procession (includes Mick McGahey) on the Miners’ Gala Day in Edinburgh in June 1969

As I was writing my book, the long-standing campaign to overturn the criminal conviction of Scottish miners from the 1984-5 strike gained momentum. I attended a witness hearing of the Scottish Government’s independent review into the policing of the strike held at the Auchengeich Miners Social Club in December 2018. Men I had interviewed were among those who recalled their experiences from over thirty years before.

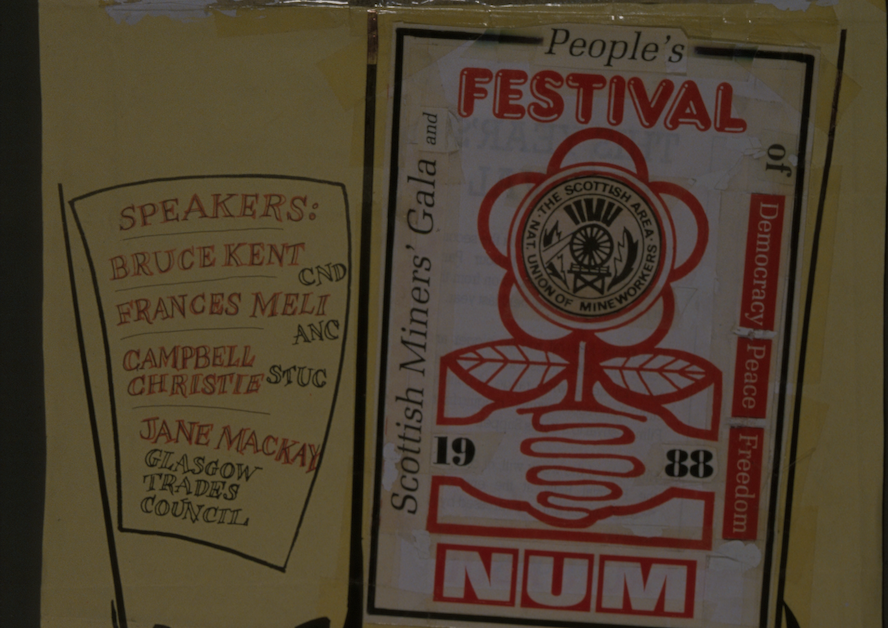

The hearing exemplified the power of oral testimonies and the role that individual and collective memories can play in achieving justice. Not all the testimonies I collected were as forthright. Others in fact revealed a thoughtful ambivalence about the effects of deindustrialization. Former miners and factory workers balanced their own personal career advancement and social mobility against the costs of increased inequality, decreased social cohesion and the diminishment of trade union power. Brendan Moohan, a former Midlothian miner, summarised that ‘it was pretty good’ growing up in the context of economic security and in a community where self-organised working-class activities such as annual miners’ galas days were central to cultural life.

In my book Coal Country, I assess Brendan’s perspective as an emblematic example of the critical nostalgia that I recorded in my oral histories. Interviewees remembered stultifying dimensions to life in socially conservative coalfield settlements, but those earlier experiences served as valuable reference points to criticise contemporary workplace disempowerment and community demobilisation.

These discussions did not end after I left Brendan’s house in Livingston, West Lothian, during February 2015. I still see him regularly when following Hibernian Football Club and Coal Country continued to be shaped by our later conversations. Similarly, I attended the Auchengeich commemoration in 2018 and 2019 following on from my interview with Willie Doolan who leads the ceremony on behalf of the Memorial Committee. He has stayed in regular contact and encouraged my research.

Writing postwar working-class history bears little resemblance to E.P. Thompson’s famous claim to be ‘rescuing’ the misrepresented radicals of the early nineteenth century. I have been lucky enough to have access to extensive archival records, but, more importantly, I have also been able to listen to the reflections of men and women who are still determining the meaning of their own past.

***

Dr Ewan Gibbs is Lecturer in Global Inequalities in the School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Glasgow

Ewan’s new book, Coal Country: The Meaning and Memory of Deindustrialization in Postwar Scotland, is published on 15 February 2021 as part of the Royal Historical Society and IHR’s ‘New Historical Perspectives’ series. Available free as an Open Access text, Coal Country is also available in hard and paperback print and Kindle from University of London Press. Print edition discounts (of 30%) are available for all: in the UK, EU & ROW using the code COAL30 from here; and in North America via University of Chicago Press using code RHSNHP30 from here.

You can also join us online for the launch of Ewan’s book: 19:00 on 25 February 2021. Booking now open.