By Ian Jackson

Environment & History, essay no. 3

In the third part of our ‘Environment & History’ series, post-graduate researcher Ian Jackson discusses his research into hydropower on the River Derwent. Inspired by his involvement in a local sustainability group, Jackson’s research investigates past hurdles and successes in England’s use of hydropower to ask how we might make better use of our sustainable resources today. The Derwent case study sheds light on age-old issues surrounding the use of water ways, suggesting these have merely shifted from conflicts of livelihoods, to conflicts of environmental preservation in recent years.

The next essay in the ‘Environment & History’ series will appear on Wednesday 17 February 2021 with ‘Using Climate History to Bear Witness: North Atlantic environmental history in comparative perspective’.

Attending my first Transition Belper (a local sustainability community group) meeting in 2010, I had no idea about the journey that one simple question would take me on: ‘Does anybody know if the Belper and Milford Mill sites are producing hydroelectric power (HEP)?’ Ten years later I started my full-time PhD research project with the School of Geography at the University of Nottingham.

The River Derwent, Derbyshire: Eco-system, Source of Power or Both?

Whilst working (since 2011) on a community owned HEP reinstatement project in a former wireworks factory on the River Derwent, and at the same time researching the historic harnessing of waterpower along the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site (DVMWHS), it has become clear that conflicts over the use of waterways are not a new phenomenon locally, and, as I am now learning, globally. Today, HEP developers in England, involved in both new and reinstatement projects, are being required to include fish passage to bypass their weirs, something that is particularly challenging in conservation areas. This additional requirement has effectively ended the development of run-of-the-river, low head, HEP for the foreseeable future, significantly increasing the capital costs in a regulated industry that restricts the price at which electricity can be sold, at a time when renewable energy subsidies are being withdrawn by the government.

Waterpower has been an important resource, supplying mechanical energy for thousands of years. It has previously suffered two major declines from which it has re-emerged. The first was the collapse of centralised government and market economy in the fifth and seventh centuries, which saw a return to human and animal muscle.[1] The development of the steam engine during the 1700s caused the second major decline, with only the development of turbines, replacing water wheels, leading to the continued harnessing of waterpower. Despite historically benefitting from water power England exploited its coal reserves in building its energy infrastructure; today Hydroelectric Power (HEP) is not being considered as an additional source of renewable energy by central government in the Energy white paper ‘Powering our Net Zero Future’ (December 2020), despite underutilised infrastructure being available. As a result, potential HEP projects in the Derwent Valley, Derbyshire, and across England have failed to progress in recent years.

My PhD research project titled, “Climate change mitigation: Learning from the past to unlock the hydropower potential of the Derbyshire Derwent Catchment (DDC)”, aims to learn the lessons of the historic use of waterpower to identify solutions to the current challenges that are preventing HEP development, and to produce a sustainable approach to enable future HEP generation.

The first stage of my research is the development of a waterpower site gazetteer for the DDC. The gazetteer captures the location, type, timeline, and current status of each waterpower site identified, by studying early OS maps of Derbyshire. The River Derwent and its tributaries run North to South through the Peak District National Park, the DVMWHS and the City of Derby, before discharging into the Trent. Of 178 historic waterpower sites identified in the DDC so far, only 8% are currently harnessing the power of the water.

The Belper Mill complex, at the heart of the DVMWHS. By 1921 the eleven iron water wheels had been replaced by ten small turbines. Today, two 175 kW 1958 Gilkes turbines harness the power of the River Derwent, supplying the national grid with HEP. Aerofilms, Aerial View of the Belper Mill Complex (1921, colourised 1947 by English Sewing Cotton Company, restored by Adrian Farmer), from the collection of the Belper Historical Society.

This article focusses on the conflict between two environmental concerns: salmonoid migration through the DDC versus the need to produce HEP renewable energy to mitigate climate change. We tend to see these as modern issues, but they have actually existed for centuries. Historic disputes, agreements and laws governing the use of water show the same conflicts arising but for different reasons. In the eighteenth century, for example, industrialists powering their mills came into conflict with local communities relying on the fish as a source of protein, particularly in Derbyshire, located so far from the sea.

Indeed, the value of the watermill to the English economy was evident as early as the Domesday survey commissioned by William I in 1085, one of the questions being ‘How much woodland, meadow, pasture, mills and fisheries?’ The total number of watermills included is approximately 6,000, with approximately 100 (corn mills) identified in Derbyshire at that time. Similarly, one of the earliest mentions of conflict on the rivers is in the Magna Carta (1215), with clause 33 stating ‘All fish-weirs are in future to be entirely removed from the Thames and the Medway, and throughout the whole of England, except on the sea-coast’. There are alternative views as to whether this relates to the rights of the fisheries or enabling navigation on the rivers.

An early example of the impact of regulation by the crown.

By 1706 an Act for the increase and better preservation of salmon and other fish in the rivers within Hampshire and Wiltshire was declared. The requirement was that all owners and occupiers of corn, fulling, paper mills, and other mills on all waters and rivers were to keep open one scuttle, or small hatch, of a foot square in the waterway or channel, allowing free passage of salmon from the 11 November to the 31 May every year. Many eighteenth and nineteenth century weirs have sluice gates adjacent to the weirs, believed to be used for flood management or weir repairs. But could they have also been a ‘scuttle’ used to allow seasonal fish passage?

One of the earliest purpose-built fish passes recorded was the ‘Sargent’s Trench’ where a channel was dug to bypass the natural and manmade barriers at the Pawtucket Falls, Rhode Island, North America in 1714, granted by the proprietors of a forge and sawmill. This is an early example of a win-win solution, with the relationship between the rural community and mill owners being relatively close as a result of the mill owners being an integral part of the local economy. In addition, the mill activity was often seasonal and intermittent, so losses of water were easier to manage. This situation changed in the middle of the eighteenth century as new industries required continuous waterpower. In 1792 a new weir built by Samuel Slater (a former apprentice of Jedediah Strutt, Milford Mills, Derbyshire,) for his second Cotton Mill, 200 yards from the Pawtucket Falls, was destroyed by fellow mill owners who had lost access to the water as the natural stream was diverted. Subsequent court cases led to the rewriting of the laws regarding water rights, fishing rights and fish passage in America; ultimately Slater was able to build his weir, raising it a further two feet with no fishway.[2]

These events show the value of viewing the waterways as a catchment, and the benefits of mill (or weir) owners working cooperatively and compromising to find solutions, rather than acting to address single issues.

Back in England, 1780-1 letters from the Strutt archives at the Derbyshire Record Office (DRO) (D3772/T2/3) between Jedediah Strutt and Sir Richard Paul Jodrell, concerning the purchase of the Hopping Mill and lands in Milford, include negotiations over the rights, leases and value of the Fish Gates within the ‘Hopping Wear’.

Were these gates allowing fish migration or were they there to solely catch fish?

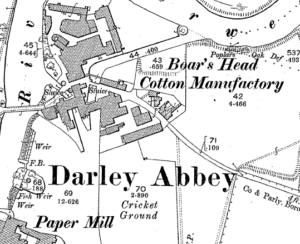

1900s OS Map showing the Fish Weir by the Paper Mill at Darley Abbey, 5 miles downstream of the Milford ‘Hopping Wear’. Photograph by Ian Jackson from original map.

Following the sudden growth of large textile mills harnessing the power of rivers in Derbyshire in the late 1700s, the Duchy of Lancaster, on behalf of the crown, commissioned a survey in 1792-4, to look at possible water ‘rents’ for the water being used by the mills and to investigate the value of the fisheries. The correspondence and reports produced by their surveyor, John Crowder, held at the DRO (D3772/E14/1/2), show the influence of the new mill owners, effectively dismissing the demand for water rents, as the mills and weirs were built on their freehold. The report also includes the ownership and quality, and therefore value, of the fisheries relating to the Rivers Derwent, Ecclesbourne, and Wye. Despite an obvious demand for fish within Derby, being so far from the available sea fish, fisheries reported relatively low numbers of fish coming from the Trent. One of the most interesting features of the report was the statement that the river near Derby would “abound with fish if not poached and destroyed”. Also, that “salmon do get this far but they are chiefly caught at a Mill belonging to Messrs. Strutt where a Frame or Heck is constructed for the purpose and which I understand has anciently been the practice” (DRO D3772/E14/1/16).

This statement alone raises the question: how did the fish pass the Trent weirs, and the textile mill weirs on the River Derwent at Wilne, Borrowash, Derby and Darley Abbey at this time, to be caught upstream in Milford or Belper, at Strutts’ mills?

In 1808 the Wards claimed damages to their farm, adjacent to the Belper Mills, following the construction of the ‘Circular Weir and Floodgates’ in 1797 and a major flood on the 6 June 1807. Two witnesses of interest offering evidence at the resultant hearing were James Oldfield and Robert Valance. James, a framework knitter, had to quickly remove his Eel Strings in two locations either side of the Belper Weir, that he was concerned he may lose in the flood. Meanwhile, Robert’s regular practice was to deploy Cleech nets to catch fish at times of flood (DRO D3772/T19/T8).

This suggests that in 1807 fish and eels in were still able to migrate the River Derwent, either relying on nature, e.g. floods, or with the help of the mill owners.

Despite most of the large textile mill owners building their weirs in the River Derwent during the late 1700s and increasing weir heights during the early 1800s, newspaper reports suggest there was salmon movement in the 1890s. In the ‘The Field, The Country Gentleman’s Newspaper’ in 1899, an article headed ‘DECREASE IN TRENT SALMON’ reported on the annual meeting of the Trent Board of Conservators. There was great concern at the lack of salmon this year, and indeed the reducing numbers over the last few years, in the River Derwent and other waterways in the country. ‘The board was at a loss to account for the absence of fish, unless it were through the pollution generally of the waters, the dry season of the last two years, or the great increase of pike in the streams where the young salmon passed in their early days’. The weirs were not mentioned in the report.

How did salmon migrate past the early industrial mill weirs for nearly a century before the numbers dropped so dramatically in the 1890s?

An example of the mill owners’ understanding of fish conservation and riverbed maintenance can be seen in the terms and conditions of the 1912 auction of the Duke of Rutland’s properties. Lot 748, the Rutland Works, Bakewell, where ‘the excellent saw mills, timber yards, house and Turbine Water Power’ (26 Horse Power) included the condition: ‘The Purchaser will covenant only to clean and cleanse the bed of the River [Wye] above such Weir, at such times as will cause the least injury to the Spawn in the River, and the least damage or hindrance to the Fishing below such Weir’.

Do the weir owners today understand their impact on the river eco-system and what they could be doing to improve the environment?

This year the DVMWHS celebrates the 250-year anniversary of the world’s first water-powered cotton spinning mill, developed at Cromford by Richard Arkwright and his partners, Jedediah Strutt and Samuel Need. One of the most interesting aspects of this development was their use of ‘drainage waters’ from local lead mines to power the first overshot wheel. The water came via an underground manmade channel, called the sough, and a wooden aqueduct over the roadway, which flowed 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The battles Arkwright faced regarding the use of the sough water ultimately led to the Cromford Mill site being closed in 1846, following the completion of the deeper Merebrook sough that diverted all the drainage waters away from Cromford. Whilst the lead mines are no longer active many of the Derbyshire soughs still have water flowing and feeding the DDC rivers. The Merebrook sough’s listing on the Historic England website states the scheduled monument continues to discharge 17 million gallons of water a day and has done since 1846; 174 years of potential waterpower not harnessed.

How much HEP from the DDC soughs, with minimal impact to the natural waterway eco system, could be harnessed today?

What other manmade water infrastructures, such as reservoirs, drinking water distribution and water treatment plants could be producing additional HEP?

Whilst the eighteenth and early nineteenth century DVMWHS mill owners could not claim to be environmentalists they understood the value of the available natural resources, such as water and fish, possibly more than many weir owners today. These early research findings show that as great problem solvers and innovators, they understood their impact along the river catchment, the need to work collaboratively, the geography of the waterways and the nature of the fish; all lessons we should be able learn from the past to help develop a win-win sustainable approach to enable future HEP development in the DDC and across England.

Brough Mill, River Noe, showing a possible ‘scuttle’ gate. Photograph by Ian Jackson.

References

- Terry S. Reynolds, ‘The Phoenix and its Demons: Waterpower

in the Past Millennium’, Transactions of the Newcomen Society, 76:2 (2006), 153-174. - Gary Kulik, ‘Dams, Fish, and Farmers, The Countryside in the Age of Capitalist Transformation’ in Steven Hahn and Jonathan Prude, eds. Essays in the Social History of Rural America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986).

***

Ian Jackson is a first year postgraduate PhD researcher, with 35 years’ experience working in the manufacturing industry, studying within the School of Geography at the University of Nottingham, supervised by Dr Susanne Seymour and Dr Stephen Dugdale.