By Philip Carter

May 2019 sees the 150th anniversary of the first examination sat by women students at a British university. Here’s the story of the nine women who took up this challenge and the questions they faced. Over the week of 3 to 7 May 2019, the IHR will be tweeting questions from each of the papers they sat.

150 years ago, at 1pm on Monday 3 May 1869, nine students sat ready to begin an examination. This, however, was no ordinary examination and these no ordinary students. Rather they were pioneers: the first women to sit a university examination in Britain—the University of London’s newly inaugurated ‘General Examination for Women’.

The exam they faced on 3 May was the first in a week-long ordeal of 11 papers, ranging from algebra to English history, modern languages to botany. They began with four hours of Latin translation, grammar and composition. Tuesday was French, then Greek, German and Italian. The mid-way point proved the most punishing: 3 hours of arithmetic and algebra on Wednesday morning followed by two papers on Geometry and Geography after lunch. On Thursday students tackled English Literature and History before finishing the week with Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and Botany.

To say that the examination required good general knowledge is to put it mildly. Questions included: ‘How is Ammonia Solution prepared in a state of purity?’, ‘What are the functions of the Roots and Leaves of Plants’, ‘How may we most conveniently classify English Irregular Verbs?’ and ‘What is the meaning of a Roman Provincia, and list those extant at the death of Julius Caesar’.

If you managed those then please: ‘Enumerate the principal rivers in North America, and the principal Islands of the West Indies’, ‘Explain the different modes of Dehiscence of Capsules’, and ‘Obtain the continued product of x+y+z, x+y-z, x-y+z, y+z-x’.

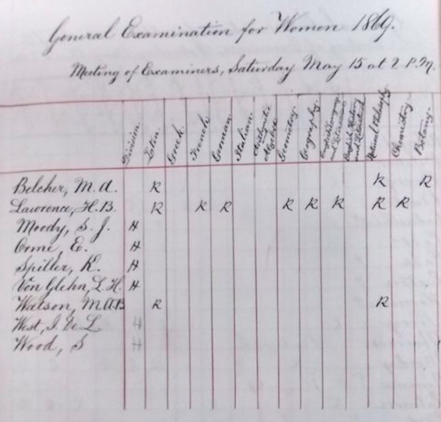

Two weeks later the University’s 17 examiners (all men) gathered to collate their marks. We know the identity of the students thanks to a one-page mark sheet now in the University archive. Six of the ‘London Nine’—Sarah Jane Moody, Eliza Orme, Louisa von Glehn, Kate Spiller, Isabella de Lancy West and Susannah Wood—were awarded ‘honours’. The remaining three students—Marian Belcher, Hendilah Lawrence and Mary Baker Watson—did not pass the exam, though Belcher re-sat successfully in the following year.

The women who took the first examination on 3 May 1869 were beneficiaries of a twenty-year campaign. Women’s higher education in London dates from the late 1840s, with the foundation of Bedford College by the Unitarian benefactor, Elisabeth Jesser Reid. Bedford was initially a teaching institution independent of the University of London, which was then itself an examining (rather than teaching) institution, established in 1836.

“Those responsible insisted that the new test be ‘on the whole no less difficult’ than the existing papers male students sat for their degree.”

Demands for women to sit examinations (and receive degrees) increased in the 1860s. After initial resistance a compromise was reached. In August 1868 the University’s Senate admitted female students, aged 17 or over, to a new kind of assessment: the General Examination for Women. Those responsible insisted that the new test be ‘on the whole no less difficult’ than the existing papers male students sat for their degree.

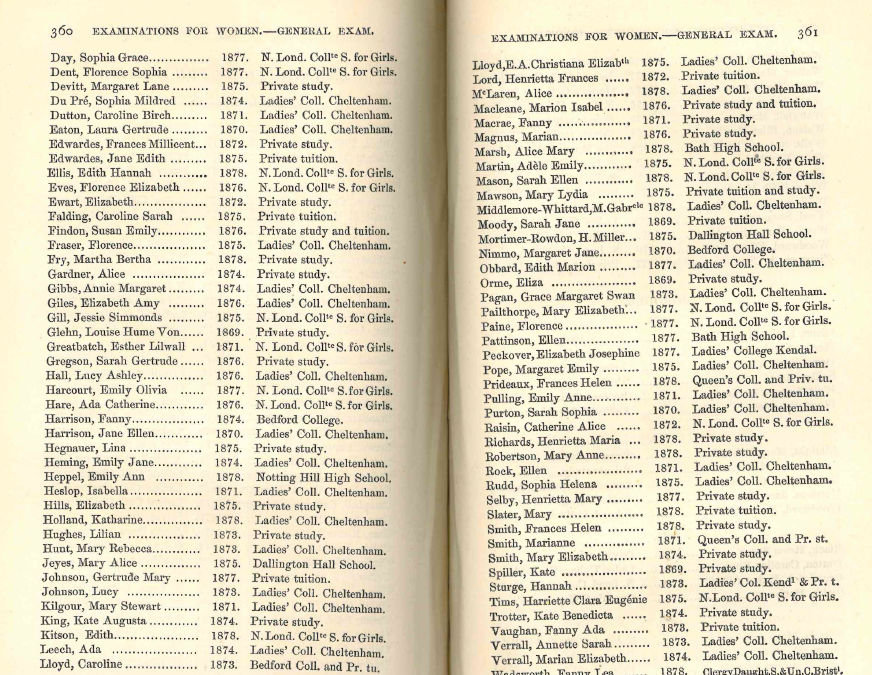

The General Examination ran for ten years and was taken by more than 250 women, of whom 139 passed and 53 awarded Honours. However, despite its rigours, those who passed the exam received only a ‘Certificate of Proficiency’. Such discrepancies did not go unnoticed. At the London’s annual awards ceremony in May 1873, Robert Lowe—the University’s MP—declared both his ‘pleasure to see women coming forward to compete’ and regret ‘that they were not permitted to measure themselves with men in the whole curriculum.’ Reported in The Times, Lowe’s call was met with ‘Cheers’; as were the names of the seven women who passed that year’s General Examination—among them the formidable Jane Harrison (1850-1928) whose individual achievements met with further cheering.

It was another five years before women were admitted to the University’s degree programme, with London once more the first British institution to offer this option to female students. Thereafter the landscape changed rapidly. Admission to London degrees was followed by the foundation of Westfield in 1882 and Royal Holloway in 1886, as women-only colleges. By 1895 10 per cent of London undergraduates were women, rising to 30 per cent within five years.

Of the nine women who sat the first General Examination in May 1869, several went on to distinguished careers. Louise Hume von Glehn (1850–1936) became a campaigner for working women and a successful biographer, translator and writer of popular histories—published under her married name, Louise Hume Creighton. In later life von Glehn also established the Creighton Lecture in History, named for her husband Mandell Creighton, and now held annually at the IHR.

“Known for her pragmatism, she later championed ‘sound-minded women who wear ordinary bonnets and carry medium-sized umbrellas’”.

Her fellow student Eliza Orme (1848–1937) took a law degree, enjoyed a successful legal career and was active in the suffrage and prison reform movements. Known for her pragmatism, she later championed ‘sound-minded women who wear ordinary bonnets and carry medium-sized umbrellas’.

Given these women’s commitment to education, it’s no surprise that at least five of the successful nine candidates went into teaching. Sarah Moody and her sisters established a preparatory school in Guildford, while Mary Baker Watson (1828–1901) worked as a governess and schoolmistress in Northamptonshire; Marian Belcher (1849–1898) became a successful headmistress of Bedford High School; and Susannah Wood—having later graduated BSc—taught mathematics in Cheltenham, Bath and Cambridge.

In 1891 Wood was appointed vice-principal of the Cambridge Training College for Women, which later became Hughes Hall, Cambridge. Kate Spiller meanwhile returned to her native Bridgwater, in Somerset, where she too was an active member of her local School Board. Clearly proud of her achievement in the 1869 examinations, she gave her occupation in the 1871 census as ‘London Univ. undergraduate’.

Spiller wasn’t the only candidate who travelled to London for the examinations: Susannah Wood came from Cheltenham and Sarah Moody journeyed from Hertfordshire.

“A lady matron was duly on hand in case of emergency.”

The potential hazards of metropolitan life did not go unnoticed. On hearing of the University’s plans, a Home Office official recommended that steps be taken ‘to prevent the excitement … which might arise from bringing these young persons up to London for examination’. A lady matron was duly on hand in case of emergency.

The Home Office need not have worried. The London Nine were characterised by an independent spirit and made their own way, professionally and personally, in adult life. Kate Spiller and Sarah Moody lived with their sisters into old age and—along with Eliza Orme and Susannah Wood—chose not to marry but to live ‘by their own means’.

Of the 139 students who’d passed the Examination by 1878, half were pupils of the country’s two leading girls’ schools, Cheltenham Ladies’ College and North London Collegiate. Others came from Bedford College, with a handful of candidates being sent from schools in Bath, Bradford, Bristol, Kendal, Liverpool, Northampton and York. Forty of the successful candidates had prepared simply with ‘private tuition’ or were self-taught. The list of those who navigated the General Examination also includes eight pairs of sisters.

Having completed the General Examination, many students returned in subsequent years to sit even harder papers in single subjects. Some returned on multiple occasions, among them the historian Alice Gardner (1854-1927) who passed a further seven ‘special certificates’ in Mechanical and Moral Philosophy, English, Political Economy, French, German and Greek between 1873 and 1878. Though latterly a student at Cambridge, Gardner continued to travel to London annually as Cambridge refused to admit women to examinations until 1882 and to full degrees before 1948.

150 years on from the first General Examination for Women we’ll soon be entering another exam season. If you’re sitting (or marking) papers in 2019 revise well, work hard and good luck. And maybe also pause to remember the ambition, intelligence and bravery of the first ‘London Nine’, who changed the course of women’s higher education over five days in May 1869.

Philip Carter works at the Institute of Historical Research and is studying the early decades of women’s education at the University of London.