This post has been written for us by Ralph Stevens, Jacobite Studies Trust Postdoctoral Fellow at the IHR, @HistoryRalph, ralph.stevens@ucd.ie

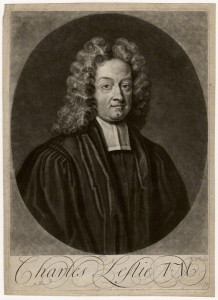

This coming September will mark the three-hundredth anniversary of the outbreak of the 1715 Jacobite Rebellion, the unsuccessful attempt to restore to the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland the male, Catholic, ‘Jacobite’ line of the Stuart dynasty, deposed in the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688-9. Though the imminent anniversary will no doubt prompt scholarly interest in the Rebellion, as a Jacobite Studies Trust Fellow at the IHR I have looked not at the military aspect of Jacobitism, but rather at a cultural – and more specifically literary – facet of the movement. My focus has been on the life and works of the Irish Protestant clergyman and ardent Jacobite Charles Leslie (1650-1722) and my aim is to use Leslie’s Jacobite propaganda as a lens through which to explore the relationships in this period between political, religious, and national identities.

Leslie’s prolific literary output – 81 publications from 1691 onwards, not counting 397 issues of his periodical The Rehearsal (1704-9) – represented one of the most significant ideological challenges to the establishment in the decades after 1688. Not for nothing would he be characterised by Bishop Gilbert Burnet of Salisbury as the ‘violentest Jacobite in the nation’. One of the very few Irish Protestants and fewer Church of Ireland clergy unwilling to at least acquiesce to regime change in 1688-91, Leslie forfeited his Irish offices – Chancellor of Connor Cathedral and Justice of the Peace for Co. Monaghan – for his refusal to swear allegiance to William and Mary or their successors. He settled in London and emerged during the 1690s as a leading Jacobite polemicist, evading arrest for his clandestine interventions in what many historians regard as an emerging ‘public sphere’, a conceptual space in which authors and actors appealed to the increasingly influential force of public opinion.

In Queen Anne’s reign Leslie’s at first weekly and later biweekly periodical The Rehearsal (1704-9) presented Tory ideology with a Jacobite edge, pricking the consciences of conservative gentry and clergy by reminding them of political and religious certainties bent or broken in the Revolution of 1688-9. Week by week Leslie engaged in polemical back-and-forth with Daniel Defoe’s Review and John Tutchin’s Observator, periodicals orientated towards the Whig party, written by Presbyterians, and presenting interpretations of the constitution in Church and State which radically differed from Leslie’s. The Rehearsal was, however, suppressed by the then Whig-dominated government in March 1708. Facing prosecution for his subversive journalism, Leslie fled in 1711 to the Jacobite court in exile at Paris. He would accompany the ‘Pretender’ James Francis Edward Stuart across Europe to Lorraine, Avignon, and Rome, but, aware of his declining health, in 1721 he obtained permission from George I’s government to return to Ireland, where he died the following year.

My research has concentrated on issues of identity displayed in Leslie’s prodigious printed works and suggests that his political identity as a Jacobite, someone loyal to the exiled Stuart dynasty, was intimately linked to his understanding of the proper relationships between England, Scotland, and Ireland. Leslie understood the link between the Three Kingdoms as not only the person of a shared monarch, but also a shared Protestant episcopalian church settlement, a group of churches governed by bishops. He displayed in his works an intense concern with Scottish affairs and particularly with harassed Scottish episcopalian Protestants, whose troubles he placed before the readers of the Rehearsal week after week. North of the border the Revolution of 1688-9 had been an avowedly Presbyterian one, not only effecting regime change in favour of William of Orange but also deposing the bishops and securing purely Calvinist government in the Scottish national church. Though he is not known to have ever visited there, Leslie’s references to Scottish affairs in fact far outnumbered references to Ireland, his place of birth, education, and early career, but it is not difficult to locate the source of this fascination.

Though born in Ireland, Leslie was in effect a second-generation Scottish immigrant. His father John Leslie (1571-1671), a native of Aberdeenshire, had been a leading clergymen in the early-seventeenth-century Scottish church, then episcopalian in structure, and had risen to become Bishop of the Isles. Bishop John had in 1633 been transferred by Charles I to the northern Irish diocese of Raphoe and there organised military resistance to first the 1641 Catholic Rebellion and then at the end of the decade the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland. Following the Restoration the elderly bishop had been rewarded for his loyalty to the Stuart dynasty by promotion to the more lucrative Ulster see of Clogher and established his family’s seat at Glaslough, Co. Monaghan. Charles Leslie, named by his father for the Stuart king ‘martyred’ the year before his birth, not only grew up in an atmosphere of fervent royalism, but partook in an ‘Ulster-Scots’ version of Irish identity, which was yet distinct in religious terms from that of the Presbyterian majority of the Scottish population settled in Ulster since the early seventeenth century. Leslie’s episcopalian Protestant identity, bound to notions of tradition, hierarchy and ceremony, transcended national borders and allowed him easily to assimilate an ‘Anglican Tory’ religious and political identity upon settling in England after the Revolution.

Leslie’s fascination with Scottish affairs suggests an explanation for his almost unique position among the clergy of the Church of Ireland, adhering to the Stuart dynasty in spite of the fact that in Ireland the brief reign of James II had been marked by a Catholic counter-revolution that threatened to overturn Protestant social and political ascendency. It seems that Leslie was a Jacobite, at the cost of his career and social standing in Ireland, as much from a desire to restore bishops to the Scottish church as from loyalty to the Stuart claimants to the throne. What differentiated Leslie from vast majority of Irish clergy, either actively supporting or acquiescing to regime change, was precisely his inherited ‘Scottishness’, for all that it was the Scottish identity of many other Ulster Protestants which made them some of William of Orange’s staunchest Irish supporters. Leslie’s intense concern for the state of the Scottish church highlights the often overlooked episcopalian strand within Ulster-Scots Protestantism, overshadowed in demographic and cultural terms by Presbyterianism, and suggests that Leslie should not be understood as an ‘Irish’ Jacobite so much as one whose identity and motivations were bound up with the politics and religion of all three Stuart kingdoms. Above all, his life and works illustrate the potential complexities of identity created by the interactions between England, Scotland, and Ireland in this period.