British History Online has now completed its digitisation of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments of England series; all volumes are now freely available to read online. The following post originally appeared on our British History Online blog.

Of the last volumes published, three related to Cambridgeshire. Our own Cambridgeshire man, Peter Salt, Editor of the Bibliography of British and Irish History, kindly agreed to write a blog post about the City of Cambridge volume. Peter writes:

When the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments’ inventory of the city of Cambridge was published in 1959 in two substantial volumes with a separate container of plans,1 they were priced at the princely sum of five guineas (£5.25). They were out of print by the time that I paid £52.00 for my copy about 25 years later. I was conscious at the time that this was virtually ten times the original selling price but I reasoned to myself that they would never be cheaper. So I greet the appearance of the Cambridge inventory in British History Online with mixed feelings – freely accessible online publication, to the high standards associated with British History Online, is a great boon to scholarship but may reduce demand for the printed volumes and therefore may have devalued my copy!

Naturally, College and University buildings fill most of the Cambridge inventory. However, it also covers the growth of the town. Furthermore, from 1946 the Commissioners were empowered not only to make an inventory of ‘Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions’ predating the eighteenth century, as had been done before World War II, but also to describe ‘such further Monuments and Constructions subsequent to’ 1714 ‘as may seem in your discretion to be worthy of mention’.2 In the Cambridge inventory, as in the preceding one covering Dorset, this resulted in the adoption of an 1850 cut-off date3and, for buildings that could be identified as being earlier than 1850, little or no selection seems to have been applied in practice. Furthermore, as the preface observed, ‘the first half of the 19th century’ was ‘a period of notable urban development in Cambridge’.4 The result was that the volumes cover not only internationally known monuments such as King’s College Chapel, but also include some quite modest terraced houses – so modest, indeed, as to include the house in which I lived from 1991 to 2005, which had been built (it was suggested) for the “outside staff” of the larger houses in the same development.5

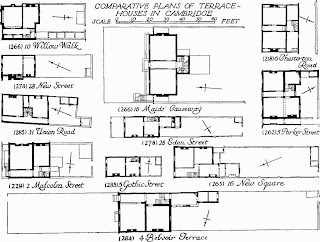

Such houses were sometimes recorded with almost as much care as the major monuments – the development of which my house formed a part is illustrated by a layout diagram and by internal plans of representative houses, the latter presented alongside plans of similar houses to facilitate comparison. Even so, there were times when the surveyors were virtually unable to find anything to say: after they had diplomatically described early nineteenth-century houses in Brunswick Walk as ‘pleasant in their simplicity and lack of ostentation’, they were reduced to reporting that ‘Willow Place and Causeway Passage … are even less distinguished than the foregoing’.6 Nonetheless, the recording and comparison of small terraced houses that were then little more than one hundred years old would have been ground-breaking at the time.

In some cases the survey recorded buildings that were soon to be demolished. Indeed, Willow Place and Causeway Passage have largely vanished. That small late-Georgian terraced houses should fall victim to 1960s and 1970s improvements is not surprising (they had been assessed in 1950 as “fourth class” and although, if they had lasted a few years longer, they might well have been refurbished and extended as desirable pieds à terre, it has to be said that our favourable view of Georgian domestic architecture rests in part on the destruction of its meanest specimens). Perhaps more surprising in a town that trades on its “heritage” is the loss of the ‘good brick front of 1727’ belonging to the Central Hotel on Peas Hill, where Pepys was supposed to have ‘drank pretty hard’ in 1660, and one of the secular buildings deemed by the Commissioners to be ‘especially worthy of preservation’,7 but replaced in 1960-2 by a hostel for King’s College.

As Professor Chris Dyer observed in his post in this blog on the Northamptonshire volumes, the Royal Commission’s post-war inventory volumes ‘marked a high point’ in its work that was not sustained. Since 1984 the Commission and English Heritage (into which the Commission was incorporated in 1999) have continued to record and to analyze, but have published the results in thematic volumes, rather than in parish by parish (or town by town) inventories. Theforeword to the last inventory volume, published in 1984, admitted that ‘the creation of an adequately researched and assessed inventory of England’s archaeological and architectural heritage is now accepted … as a complex and infinite task’ (my emphasis). Indeed, what seems ‘adequately researched and assessed’ to one generation may disappoint the next one. Now that Causeway Passage has vanished from the map we might well wish that the inventory had gone into a bit more detail. And, just as 1714 came to seem, after World War II, too remote an end date for the survey, resulting in an expansion of the Commissioners’ remit, the 1850 cut off chosen for the Cambridge volumes will seem too remote to those who want to study Cambridge’s later nineteenth-century growth. In practice, though, we must be grateful for what was achieved, and (notwithstanding the potential decline in the value of my printed copy) the online publication of the inventories is very much to be welcomed.

1 All footnote references are to the city of Cambridge inventory. The volumes were continuously paginated and are treated as a single entity by British History Online.