This is a guest post from Jonathan Blaney (IHR). Jonathan is the project editor for British History Online.

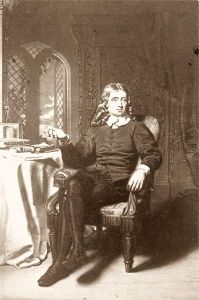

Had Keats lived, there would have been a rival. But as it is, there is no one to touch Milton as a master of English poetry and of prose. It was one of the pleasures of Quentin Skinner’s Creighton lecture that he used it, as he himself remarked, as an excuse to quote some of the finest passages of seventeenth century prose.

Had Keats lived, there would have been a rival. But as it is, there is no one to touch Milton as a master of English poetry and of prose. It was one of the pleasures of Quentin Skinner’s Creighton lecture that he used it, as he himself remarked, as an excuse to quote some of the finest passages of seventeenth century prose.

One of Skinner’s main points was that Milton’s conception of liberty was not, as is dominant in modern thought, freedom of action; rather it is freedom from the arbitrary power of another. In Milton’s time this arbitrary power was expressed above all by the royal veto, or “negative voice”, and is one of the principal planks of Milton’s argument against the institution of monarchy. Here Skinner quoted a splendid passage from The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates

“Surely they that shall boast, as we do, to be a free nation, and not have in themselves the power to remove or to abolish any governor supreme, or subordinate, with the government itself upon urgent causes, may please their fancy with a ridiculous and painted freedom, fit to cozen babies.”

As Skinner made clear, trenchantly, in the Q&A session after the lecture, the Royal prerogative still stands in the UK.

Skinner began by saying that he would concentrate on the two decades when Milton published his political writings, 1640 to 1660, after which censorship prevented further publication. Nevertheless I was hoping that he would talk about Paradise Lost. Happily Skinner said that for the last 10 minutes he would rashly venture into the territory of the great poem and the question of Satan, the parliament of fallen angels, and the question of freedom – questions which have preoccupied literary critics since at least Empson.

Quoting parts of books II and V, Skinner argued that the poem does indeed refract Milton’s feelings for the Restoration – that a servile people can come to prefer servility, in contrast to the courageous fallen angels:

“Free, and to none accountable, preferring

Hard liberty before the easie yoke

Of servile Pomp”

(II.255-7)

If I understood correctly, Skinner was saying that God does not enter into this notion of liberty, from Milton’s perspective. Nevertheless, this remains one of the hard questions of Paradise Lost – the reader feels that God does enter into the question. For example, when Skinner was talking of the servility of being dependent upon the arbitrary will of another, I immediately thought of the War in Heaven passage of Paradise Lost. At the end of Book VI it is related that God’s army stands aside and allows Christ alone to drive the rebels:

“to the bounds

And crystal wall of heav’n, which op’ning wide

Rolled inward, and a spacious gap disclosed

Into the wasteful deep”

(VI.859-62)

By the arbitrary will of God, a gap appears in heaven and the rebels are pushed through it. Is this not the epitome of being at the mercy of the arbitrary will of another? Could the most Christian reader take this as anything other than, militarily, a rather shabby trick?