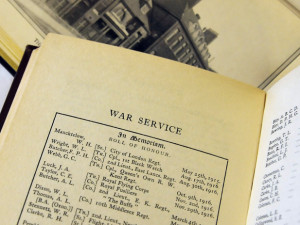

The IHR library has an outstanding collection of university and school records. Following on the theme of this year’s Anglo-American conference, we’ve been looking at what they contain about the First World War. School registers often have lists of teachers and former pupils who served or were killed in the war. School histories and journals include more descriptive accounts, and there are some vivid records, sometimes poignant, but mostly emphasising how schools attempted to continue as usual.

Several describe how school playing fields were ploughed up to be used as allotments worked on by the pupils: at St Peter’s School in York a ‘vegetable committee’ was formed (Raine, A., History of St Peter’s School, York, p.189). In A History of Kibworth Beauchamp Grammar School, we read how the congested state of the railways made it difficult to get equipment and books (p. 69). Availability of food is often an issue – Records (1909-1992) of the Ramsgate County School for Boys gives praise to Mrs Read: “the fact that we were able to have.. any dinners at all was largely due to the way she managed to secure food-stuffs in unorthodox ways” (p. 115).

Several describe how school playing fields were ploughed up to be used as allotments worked on by the pupils: at St Peter’s School in York a ‘vegetable committee’ was formed (Raine, A., History of St Peter’s School, York, p.189). In A History of Kibworth Beauchamp Grammar School, we read how the congested state of the railways made it difficult to get equipment and books (p. 69). Availability of food is often an issue – Records (1909-1992) of the Ramsgate County School for Boys gives praise to Mrs Read: “the fact that we were able to have.. any dinners at all was largely due to the way she managed to secure food-stuffs in unorthodox ways” (p. 115).

The stress caused by the threat of air raids is a recurrent theme. Air raid shelters were created in cellars and cloakrooms and under school lawns. History of St Peter’s School tells of Zeppelin attacks in York and a boy being injured by shrapnel (p.189). At Ramsgate County School for Boys, a bomb fell on the tennis court, demolishing a summer house and breaking windows (p.100). In general people coped, and school life continued, though classes started a little late the morning after a raid (p.113).

The Book of the Blackheath High School gives two first-hand accounts by former pupils. The war affected not only the girls’ daily life at school but also their attitudes to the role of women in the future. At a school speech day, the Bishop of Woolwich said “Now.. is women’s chance to use wisely and well the great force and power of work of which this War has shewn them to be possessed” (p.170).

The girls were keen to help with war work. A former sixth former describes how “It was difficult to read for the University when one was consumed by a desire to go out and do something of immediate use..”, but “well-equipped women would be needed in the post-war future, so we stayed on” (p.171). One girl was called up for service in France and “was seen off by an admiring and envious crowd of seniors who could have given all they possessed to have been going too” (p. 172).

Girls at the school helped out in their own time by working in allotments, canteens, and factories, packing parcels, and doing Red Cross work. Sixth formers knitted under the table to be “safe from the eyes of the Head and the Staff, who discouraged that mixture of fervid patriotism and intermittent reading which is apt to result in a low place on university scholarship lists” (p.172). Again, the “unchanged and steady way in which the life of the school went on” is emphasised. A younger pupil described school life as a relief from the troubles of the outside world (p. 176-7).

Other school histories recount the departure of male teachers to serve in the war and the arrival of female replacements, the activities of the officer training corps, war savings work, and the planning of memorials for former pupils and masters.

The material can be found in the Biographical section of the British collection. School records are also located in the record society series within the Scottish, Welsh and English local history sections.

Sources

- Raine, Angelo, History of St. Peter’s School, York : A.D. 627 to the present day, London : G. Bell, [1926]

- Elliott, Bernard, A History of Kibworth Beauchamp Grammar School, 1958

- Malim, Mary Charlotte, Book of the Blackheath High School, London : Blackheath, 1927

- Chatham House School, Records, 1909-1922, of the Ramsgate County School for Boys now known as Chatham House School, Chatham House, 1923