This blog post was written by Claire Langhamer, Director of the IHR.

One of the most striking trends within recent historical research has been the ascendancy of the history of emotion, encouraged in no small part by the critical mass generated by specialist intellectual centres in Berlin, London, and Australia. The origins of this approach are commonly traced back to Lucien Febvre’s exhortation to study sensibilities, feeling, and history in the face of the rise of fascism in Europe.[1] However it was not until Peter and Carol Stearns introduced the concept of ‘emotionology’ in the 1980s that emotional standards and codes became a focus of sustained research.[2] By the early twenty first century, new formulations such as Barbara Rosenwein’s ‘emotional communities’ and William Reddy’s ‘emotives’ provided innovative conceptual frameworks for a growing area of study; more recently Monique Scheer’s notion of ‘emotional practice’ has helped historians foreground embodied emotional experience.[3]

Notwithstanding this recent ‘emotional turn’, historians have long taken an interest in how people felt, how they were told to feel, and the dynamic interplay between practice and prescription. In fact, the history of emotion has deep and wide roots within the discipline and is in active conversation with rich seams of research on social relations, subjectivity, experience, everyday life, and intimacy. Our knowledge of past feeling emerges out of a diverse range of approaches and concerns, some of which predate the history of emotion itself. As Laura Carter has recently shown, popular social historians in Britain before the Second World War regarded feeling as a methodology as well as an object of study.[4]

The history of emotion has engaged productively with other disciplines too, providing an instructive case study of the benefits of working across humanities-social science-science divides. For example, current research on feelings and work draws heavily on sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild’s 1983 exposition of emotional labour in the airline and debt collecting industries.[5] The thinking of cultural theorist Sara Ahmed has been notably influential in encouraging historians to consider the work that emotions have done in the past.[6] Aspects of what we now frame as the history of emotions can also be found within women’s and gender history, family history, queer history, histories of science and medicine, political history, and even diplomatic history, to name just a few examples. The challenge when surveying such a vibrant and self-consciously emergent field is to welcome the new without effacing the old.

The Bibliography of British and Irish History (BBIH) offers an unparalleled way-in to surveying trends within this ever expanding field. It allows us to map new developments whilst surfacing their origins and attending to the paths not taken. The quantity of emotions work is noteworthy. The BBIH emotions reading list identifies 521 publications over the last three years alone. Across the bibliography as a whole there are details of over 2,400 records as of January 2024. The list speaks to a growing diversity of approach and focus within this field as well as to its temporal depth and its geographical range. This is an area within which people are doing complex, theoretically informed and methodologically exciting research.

As might be expected, the 2020-2023 list includes publications that foreground individual emotions—love and happiness, grief and fear, empathy and shame, for example. It covers the feelings of particular groups including children, refugees, and migrants, but it also speaks to a growing interest in materiality—including the emotional lives of objects. It reflects work on relationships with non-human animals as well as with particular places and spaces. Some of the works listed here attend to the emotional economy of specific activities such as holiday-making or even criminality; others to occupations, world events, or political moments. There are studies located within the history of popular culture, the history of intimacy, and the history of colonialism and empire. There are also publications that explore broader structures of feeling or which identify emotional hierarchies. Such studies illuminate the relative value of emotional actors as well as the traces that different emotional lives leave within the historical record.

The current vitality of the history of emotions is rooted in our sense of the present as well as our understanding of the past. It is often suggested that we live in distinctively emotional times, even as we are urged to ‘be wary of ahistorical ideas that imply specific emotions—anger, anxiety—[are] more prevalent than in previous decades.’[7] In recent years emotion has gained purchase as a way of knowing and engaging with the world whereby authentic feeling, above and beyond attitude or even belief, is perceived to facilitate a democratic and increasingly embodied response to social worlds and everyday politics. Within contemporary society feeling is deployed to support knowledge claims, demand rights, cohere collective organisation, and facilitate resistance. Given this context it is perhaps not surprising that historians are keen to explore particular emotions, to deploy emotion as a category of historical analysis, and even to reflect on their own emotional positionality and on the status of feeling as historical methodology.

[1] For an English translation of Febvre’s 1941 intervention see ‘Sensibility and History: How to Reconstitute the Emotional Life of the Past’, in Peter Burke (ed.), A New Kind of History: From the Writings of Febvre (London: Harper & Row, 1973), pp. 12-26.

[2] Stearns, Peter and Stearns, Carol, ‘Emotionology: Clarifying the History of Emotions and Emotional Standards’, The American Historical Review, 90:4, 1985: pp. 813-836.

[3] Rosenwein, Barbara H., Emotional Communities in the Early Middle Ages (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006); William M. Reddy, The Navigation of Feeling: A Framework for the History of Emotions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

[4] Carter, Laura, Histories of Everyday Life. The Making of Popular Social History in Britain, 1918-1979 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021).

[5] Arnold-Forster, Agnes and Moulds, Alison (eds.), Feelings and Work in Modern History. Emotional Labour and Emotions about Labour (London: Bloomsbury, 2022).

[6] Ahmed, Sara, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press: 2004).

[7] Davies, William, Nervous States. How Feeling Took Over the World (London: Jonathan Cape, 2018); Moss, Jonathan, Robinson, Emily and Watts, Jake, The Politics of Feeling in Brexit Britain. Stories From The Mass Observation Project (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2024), p.180.

IMAGES

Banner image: Ramsgate Sands by William Powell Frith (1854).

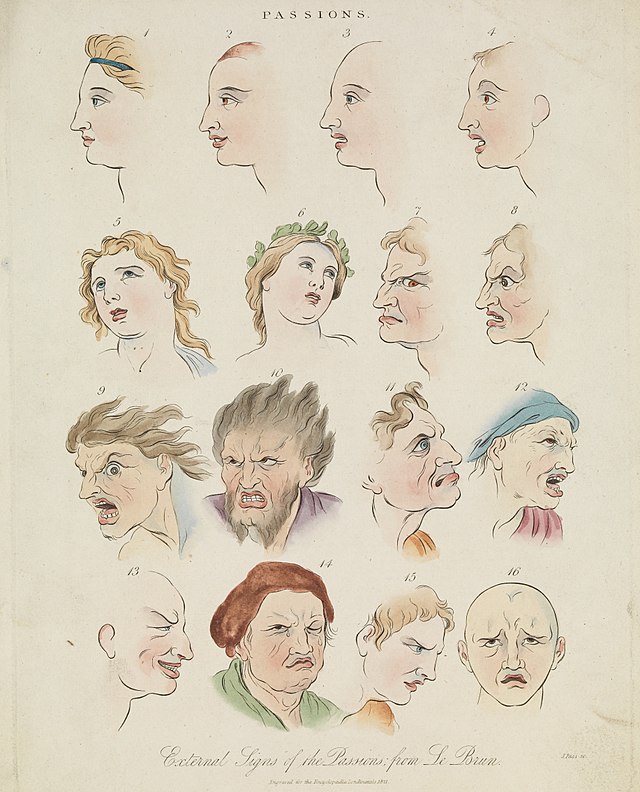

Article image: Sixteen faces expressing the human passions. Coloured engraving by J. Pass, 1821, after C. Le Brun. Wellcome Images, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0