This blog was written by Michael Townsend, Collections and Metadata Librarian at the IHR Wohl Library.

While Macbeth is familiar to many, being one of William Shakespeare’s most renowned plays, the same may not be said about the actual Macbeth who reigned in the eleventh century. Here we explore some of the sources of the play, editions of which can be found in the Institute of Historical Research library. Representations of the Three Sisters, or ‘witches’, will be considered as well as the depiction of Macbeth, and how both are ultimately linked to James VI/I who had sat on the English throne for only three years when Macbeth was first staged in 1606.

‘This Fiend of Scotland’

The Macbeth we get in the play is one that, while briefly equivocal about committing murder, seems begrudgingly accustomed to it by Act 3, marked by the cold calculation in which he plans the murder of Banquo and his son, Fleance. By this time Shakespeare’s Macbeth fall is rapid and total: ‘I am in blood / Stepped in so far, that should I wade no more, / Returning were as tedious as go o’er.’ [3.4.134–36]. To a degree this is reflected in the historiography contemporary to Shakespeare, although he did make several significant changes, motivated by the needs of a dramatic plot and being aware of potential audiences for this work.

One of the most obvious differences is the passage of time. Macbeth’s reign was relatively lengthy, being King of Alba from 1040 to 1057. Fifteenth and sixteenth century Scottish historians chart this period and plot Macbeth’s descent into tyranny over several years: in a verse translation of the history by Hector Boece (1465–1536) the initial period of his reign is portrayed as being exemplary, ‘Baith speir and scheild to all kirkmen wes he / And merchandis alss that saillit on the se / To husband men that labourit on the grund / Ane better King in no tyme mycht be fund…’ [lines 39,953–56]. This too is reflected in a translation from French to Scots of a history by David Chalmers (1530–1592): ‘In the beginning schwaing him selff werrie religious, and ane gude Justiciar, makand mony gude lawis to the adwancement of the seruice off God…’ [page 53]. Earlier sources stress this initial period of peace even further and depict Macbeth as a good king: The Prophecy of Berchán written in the eleventh century describe him as, ‘the generous king of Fortriu’, and ‘The red, tall, golden-haired one, he will be pleasant to me among them’ This initial period of stable government is not hinted at in Macbeth. Understandably in Shakespeare’s briefest tragedy, the speed in which he ponders the murder of Duncan to killing Macduff’s family is rapid. Shakespeare’s focus was his audience, and like many works of historical fiction, plot and character development needed to take precedence over historical narrative.

Shakespeare’s audience, and one potential audience member in particular, James VI/I, may have influenced Shakespeare indirectly, when he was putting the plot of the play together. Numerous times Banquo is stated as the founder of a line of kings: ‘Lesser than Macbeth, and greater. / Not so happy, yet much happier / Thou shalt get kings, though thou be none;’ [1.3.65–7]. Banquo was believed to be the common ancestor of the Stuarts, and thus of James VI/I himself. Banquo is portrayed in the play as being far more naturally immune to tempting prophecies of the Three Sisters and is one of the first to suspect Macbeth may have won the throne by murder: ‘Thou hast it now, King, Cawdor, Glamis, all / As the weïrd women promised, and I fear / Thou played’st most foully for’t.’ [3.1.1–3]. In Act 3 he is soon murdered to satiate – unsuccessfully – Macbeth’s growing paranoia.

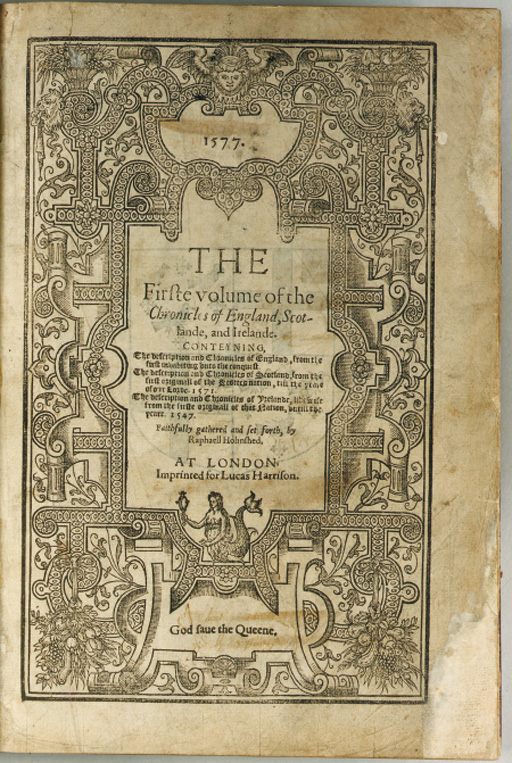

The main plot for Macbeth, like many of Shakespeare’s history plays, was Raphael Holinshed’s The Chronicles of England, Scotlande and Irelande. Shakespeare does make one small but highly significant change to Holinshed’s narrative. Before the murder of Duncan, Macbeth, ‘communicating his proposed intent with his trustie friends, amongst whom Banquho was the chiefest, vpon confidence of their promised aid, he slue the king…[vol. 5, p. 269]. Banquo had full knowledge of the assassination plot and even aided Macbeth in his aim. Shakespeare wisely altered this narrative to cast James VI/I’s ancestor as a noble victim, aware of Macbeth’s future, but not how he would achieve it.

‘When Shall We Three Meet Again’: Shakespeare’s Sisters

While Banquo links Macbeth to James VI/I so too do the figures of Shakespeare’s witches. Even a cursorary knowledge of James highlights his deep fear of witchcraft, having written a tract, Demonologie, on the subject. More generally the figure of the occult practitioner is one that appears several times in late Elizabethan and Jacobean drama. As well as linking his play to the new Scottish dynasty, Shakespeare was also tapping into a contemporary fascination and deep dread of the occult.

In Macbeth Shakespeare is quick to enrobe the Three Sisters in the typical trappings of the early modern witch. In Act 1, Scene 1 it is established they have familiars [1.1.8] and the ability to fly [1.1.9–10]. In Act 1, Scene 3, before Macbeth and Banquo arrive, the Sisters discuss how one of them had been agrieved by a sailor’s wife:

1st Witch A sailor’s wife had chestnuts in her lap,

And munched, and munched, and munched.

‘Give me’ quoth I.

‘Aroynt thee witch’ the rump-fed ronyon cries.

Her husband’s to Aleppo gone, Master o’th’

Tiger:

But in a sieve I’ll thither sail,

And like a rat without a tail,

I’ll do, I’ll do, I’ll do.

2nd Witch I’ll give thee a wind.

1st Witch Th’art kind.

3rd Witch And I another.

1st Witch I myself have all the other,

And the very port they blow…[1.3.4–15]

The power to raise storms was another ability it was believed early modern witches possessed and would have been familiar to many, including the King, since it had been a prominent episode in the North Berwick witch trials of the 1590s. In the popular pamphlet, Newes from Scotland, Agnes Sampson – believed to be the chief witch during the trials – related how she and a number of other witches raised a tempest which endangered James VI’s ship on its return voyage from Denmark.

While these early signs identify the Three Sisters as witches, there are further efforts to link them to the semiology of early modern witchcraft. Although the Devil is not present in the play, Hecate, goddess of witchcraft, is. There is some doubt to what degree Shakespeare wrote her scenes (Act 3, Scene 5 and part of Act 4, Scene 1), possibly being the work of his contemporary, Thomas Middleton. However, their inclusion in most productions reinforces the image of the Three Sisters conforming to recognisable tropes of the early modern witch.

Like many matters regarding Shakespeare, however, things are not that simple. There are some important differences between Shakespeare’s witches and other prominent occult practitioners in early modern drama. Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus is human, flawed and pays a tragic – and visceral – price, for his occult practices. Similarly, Elizabeth Sawyer, in The Witch of Edmonton, is an old women, shuned by the community, but very much human. During the play she is tempted into the Devil’s service, as he takes the form of a large black dog, and like Doctor Faustus, is dead by the end of the play. What the Three Sisters are is far from clear. When they do make an appearance in earlier sources, they often seem like supernatural beings rather than human witches. In The Cronykil of Scotland by the late medieval poet Andrew of Wyntoun, the ‘Werd Systrys’ come to Macbeth in a dream and make their prophecies [Book 6, Chapter 18]. Later in the historiographical record, Holinshed, Shakespeare’s primary source for the play, refers to them as, ‘resembling creatures of elder world’, while a printed note in the margin names them as ‘the weird sisters or feiries’ [vol. 5, p. 268]. It is possible that the ‘witches’ have a more otherworldly or even divine origin. Being named Weird may not relate to strangeness, as it does today, but the Old English word ‘wyrd’ meaning fate, suggesting Shakespeare’s ‘witches’ are closer in nature to similar triads of mythological goddess-prophets like the Greek Fates or the Norns of Norse myth.

This brief overview of the resources behind the play Macbeth is far from exhaustive but readers (and potential readers) are very welcome to explore our collections for further material on this play and Shakespeare’s other works. In fact, in a blog written by my colleague, Sophia Benko, one can explore the rich and extensive works in our collections about Henry VIII.

The First Folios at 400

The First Folio was first entered into the Stationers’ Register on this day (8th November) in 1623. To celebrate 400 years since this historic publication, the School of Advanced Study and Senate House Library are hosting an exciting programme of events and activity including a major new exhibition, Shakespeare’s First Folios: A 400-year journey which opens on the 21 November.

To view the full programme, visit: https://www.sas.ac.uk/shakespeares-first-folio-400