This blog post was written by Sophia Benko, Graduate Trainee Library Assistant at the IHR Wohl Library.

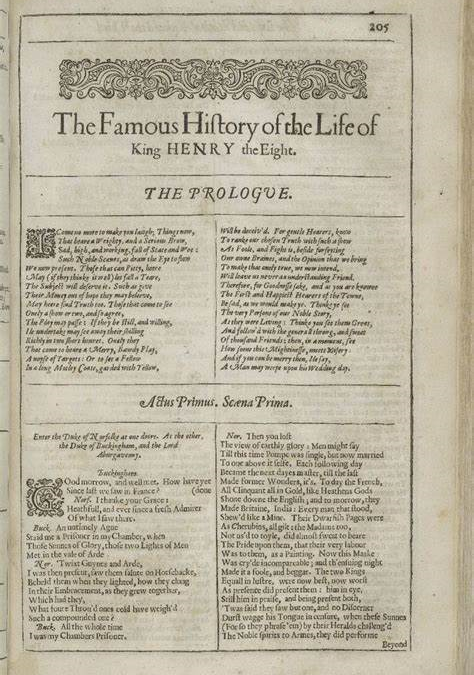

While librarians always live in fear of fire destroying their collections, in celebration of the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s First Folio, I would like to face my fears and focus on Henry VIII, the play that famously caused the Globe Theatre to burn down in 1613. This anniversary is particularly important to Henry VIII, as the Folio was the first time that the play appeared in print.

Moving beyond the widely accepted argument that John Fletcher may have written more than half the play, I would like to focus on the historical sources of the play, as well as the relationship between women in the play and real life.

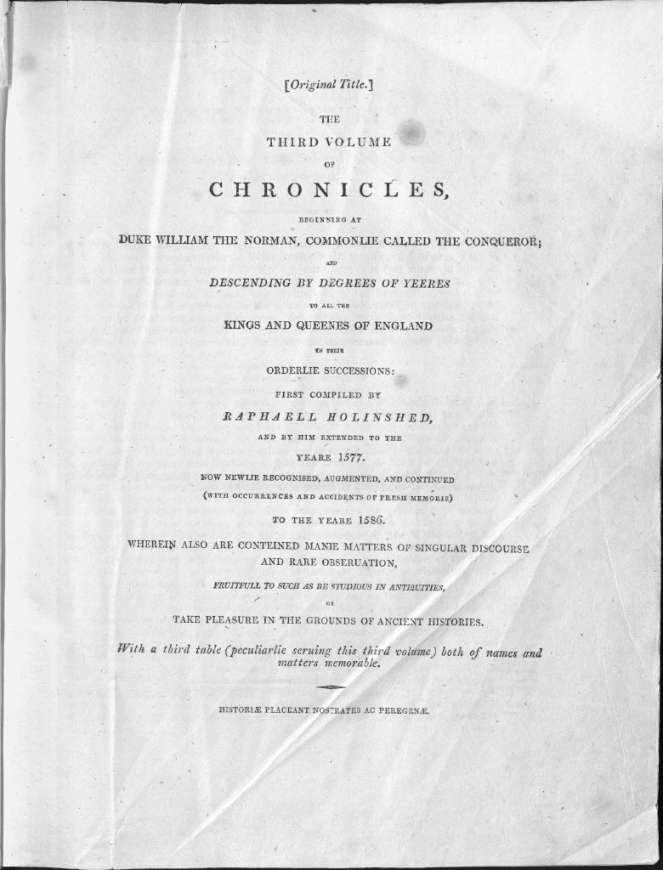

Shakespeare’s use – and lack thereof – of sources in the play is complex. According to Geoffrey Bullough, Henry VIII relies less on historical sources than any of Shakespeare’s plays – Bullough argues there are only three noticeable sources used in the play, whereas other history plays, such as King John and Henry V, use six each. These three sources are a play – Samuel Rowley’s 1605 work When You See Me, You Know Me – and two historical works, the 1587 edition of The Third Volume of Chronicles by R. Holinshed and the 1583 edition of Foxe’s Actes and Monuments of Martyrs. For those seeking to further immerse themselves in Shakespeare’s world, an 1807 reprint of the Chronicles can be found in the IHR library, while a facsimile of the exact 1583 edition of Foxe’s Actes Shakespeare likely used and a copy of the play When You See Me, You Know Me, are available among the IHR’s many e-resources.

However, with so few historical sources to build on, Shakespeare’s relationship to historical accuracy in the play is complex. An alternative title is ‘All Is True’, and the prologue stresses that this play is about the characters ‘As they were living’. Nonetheless, Shakespeare also clearly does not follow a historically accurate timeline. Henry’s 1533 marriage to Anne Boleyn takes place before the fall of Cardinal Wolsey in 1529, and the death of Katherine of Aragon in 1536 precedes the birth of Elizabeth I in 1533. While it is hard to say exactly how much audiences would have picked up on these discrepancies, the play also problematises the idea of one true version of history. The play starts with reports of the famous Field of the Cloth of Gold. However, the rivals Norfolk and Buckingham view and present the meeting in entirely different ways. Norfolk praises the event for being an occasion of splendour and greatness, whereas Buckingham describes the event as useless extravagance. Moreover, while using pro-Protestant sources such as Foxe’s work, Shakespeare presents positive views of Catholic characters. Upon learning of Cardinal Wolsey’s death, Katherine of Aragon breaks into a denunciation of him as a proud, ambitious intriguer, a liar and equivocator; but her physician Griffith counters with an alternative view, praising him as a great scholar, wise and eloquent, and a princely benefactor. Although these accounts are contradictory, they could both be true, for they are not mutually exclusive, and Katherine learns to see another kind of truth here: ‘’Whom I most hated living, thou hast made me,/With thy religious truth and modesty,/Now in his ashes honour: peace be with him.’’ Truth is, ultimately, problematic, and Shakespeare in some ways has moved beyond the Tudor’s narrative of the 16th century.

Alongside this complex relationship with history, the context of the play is also deeply interesting. What often strikes most readers and audience members about the play is how the play dramatically ends – to quote the Shakespeare Birth Trust: ‘’Queen Elizabeth is the most extraordinary being ever to be born, praise her.’’ No executions follow, nor an exploration of why, after Henry VIII divorced Katherine of Aragon to have a son, the play happily ends with the birth of another daughter. This pro-Elizabeth stance in 1613, ten years after her death, confused certain 18th- and 19th-century scholars, who dated the play’s composition to before 1603 as such praise could not have been written under James I, who they argued hated the memory of Elizabeth I. These scholars including Samuel Johnson and Edmond Malone, whose works The Plays of William Shakespeare and The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare, respectively, can be found in the Senate House Library. Others, however, have suggested that the play is entirely in praise of Protestant women. Henry VIII is believed to have been first performed as part of the ceremonies celebrating the marriage of James I’s daughter, Princess Elizabeth in 1612–1613. Princess Elizabeth and her husband, Frederick V of the Palatinate, were noted Protestants and their marriage was highly popular. Elizabeth I had been Princess Elizabeth’s godmother, and therefore exalting their joint glories was a highly popular move when fear of Catholics was ever present. The portrayal of Anne Boleyn is also muted – the play ends before her execution or her being accused of incest, and she is portrayed as chaste and unwilling to become rivals with Katherine of Aragon. The comparison between the two Queen Annes, Anne Boleyn, and Princess Elizabeth’s mother Anne of Denmark, therefore, can also be made, with two beautiful Annes birthing staunchly Protestant Elizabeths who would defend their country and religion against Catholics. Here, Shakespeare relies less on historical sources, but draws on another source – that of public memory – to connect the memories of these women, particularly Elizabeth I, whose reign had only ended a decade prior.

Henry VIII, therefore, presents a complex relationship with its historical context and sources, which can be explored further in the IHR Wohl Library at any time. A blog written by my colleague, Mike Townsend, explores the fascinating sources behind one of Shakespeare’s best-known plays, Macbeth.

Sophia Benko, Graduate Trainee Library Assistant, Institute of Historical Research Wohl Library

First Folios at 400

Shakespeare’s First Folio was first entered into the Stationers’ Register on this day (8th November) in 1623. To celebrate 400 years since this historic publication, the School of Advanced Study and Senate House Library are hosting an exciting programme of events and activity including a major new exhibition, Shakespeare’s First Folios: A 400-year journey which opens on the 21 November.

To view the full programme, visit: https://www.sas.ac.uk/shakespeares-first-folio-400