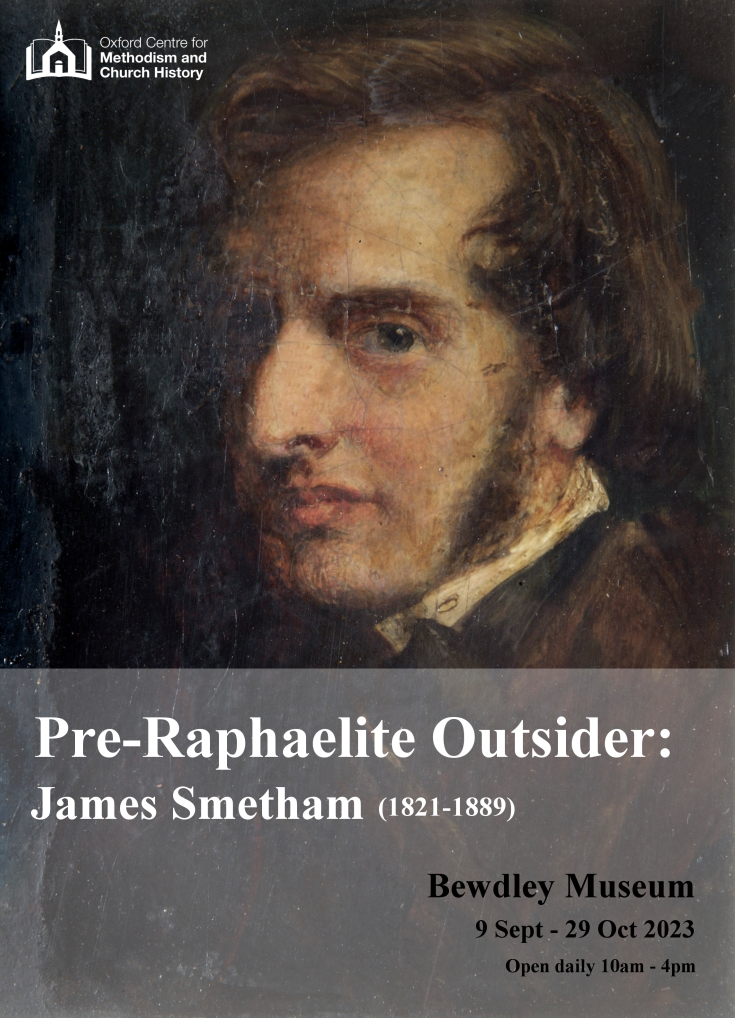

Since 2019 a team of archivists, creative practitioners, curators, and researchers have been exploring the life and work of the little-known artist and devout Methodist James Smetham. In this blog post, Dr Ruth Slatter (IHR Lecturer in Historic Environment and Knowledge Exchange) introduces the new exhibition they have curated—Pre-Raphaelite Outsider: James Smetham (1821-1889)—which is currently on display at Bewdley Museum until 29 October 2023.

James Smetham (1821-1889) was an artist and devout Methodist. Born in Pateley Bridge (Yorkshire), at 16 he began training as an architect before entering the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) as a probationer in 1843. However, never successfully appointed as a student of the RA, Smetham initially forged a career as a portrait painter, before becoming an art teacher at Westminster College, an educational institution for the preparation of Methodist teachers. Teaching here from 1851 to 1876, Smetham also (largely unsuccessfully) submitted paintings to the RA and other regional art academies, made a huge number of smaller paintings and etchings, wrote poetry, and published critical reflections on the work of William Blake.

Many of Smetham’s paintings demonstrate his stylistic and practical association with the contemporary Pre-Raphaelite artists. Smetham was particularly good friends with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Frederick J. Shields, and Ford Madox Brown and embraced their mystical and romantic style and subject matter. However, for several reasons, Smetham was never a core member of this group and never had the same commercial success as his friends.

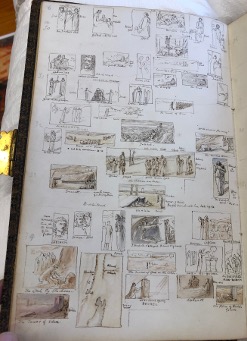

Firstly, the son of a Wesleyan Methodist minister, Smetham was committed to the Methodist Church throughout his life. This religious identity provided him with an established network for portrait commissions and considerable subject matter for his creative practices. For example, in his journals he made visual reflections on all 31,102 verses in the 66 books of the Bible, between 1851 and 1871. However, Smetham’s personal faith also meant that he was discomfited by the behaviour of the Pre-Raphaelites—and nineteenth-century artistic circles more broadly—that did not align with his beliefs. As a result, Smetham did not consistently attend the events where his contemporaries developed and maintained the networks required for commercial artistic success.

Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History, SME/1/5/2. Used with permission.

Smetham’s artistic career was also disrupted by his poor mental health. Described as ‘depression’, a ‘state of darkness’, and a ‘lowered tone’ (by Smetham, his wife, and his friend Dante Gabriel Rossetti), Smetham’s ill health resulted in months of agoraphobia and an inability to create. In 1856, Smetham’s mental fragility also led him to flee the noise and busyness of central London and move to Stoke Newington on the northern outskirts of the mid-nineteenth-century city. Here he found a quiet, calm, and almost rural environment that afforded him a conducive working atmosphere. But, as he frequently reflected on in his letters and journal entries, living in Stoke Newington also separated him from his artistic networks and the central London art market.

Smetham’s artistic creations are still little known to this day. Since his death, Smetham has been the subject of several biographies. However, these publications have largely focused on Smetham as an inspiration for contemporary Methodists, or have studied him as a peripheral member of the Pre-Raphaelite community. And the largest single collection of Smetham’s art, poetry, and papers (held by the Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History (OCMCH)) has only been on public display once—nearly 30 years ago in an exhibition at Yale University in 1995.

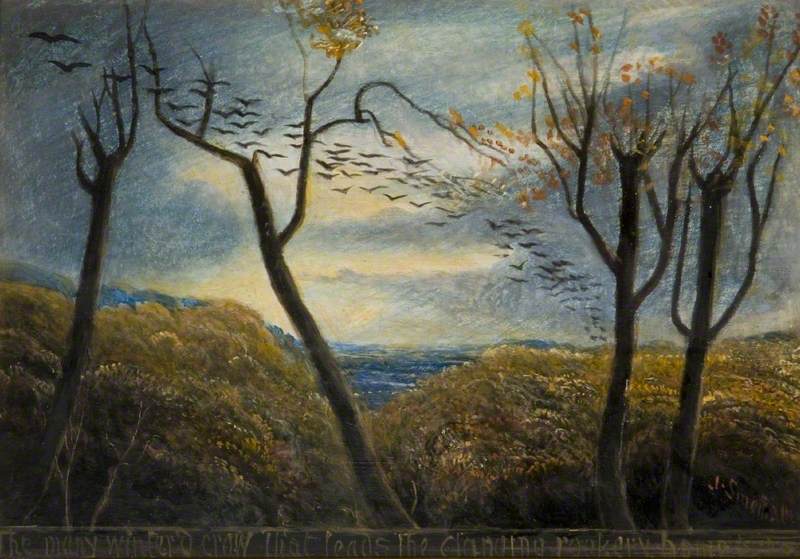

In 2019, I began to work with OCMCH to find ways to raise the profile of Smetham and his artistic creations and to emphasise how a long overdue reconsideration of his art speaks to contemporarily pertinent issues. Firstly, many of Smetham’s artistic creations are beautiful reflections on the atmosphere of the places he knew and loved. While he rarely made accurate representations of specific places, he often conveyed the emotional affect of places. For example, A Quiet Meadow (Eastbourne, East Sussex), captures the peace and calm of this place, reflecting how Smetham regularly visited Eastbourne to recuperate from the strains and pressures of London life.

As I have recently discussed in an open access article in the Journal of Historical Geography (available here) and a video about Smetham’s Orrery of Personal Responsibility (available here), Smetham’s artistic creations also often captured the importance and impact of his relationships. This is reflected in Hugh Miller Watching for His Father’s Vessel (1866). Miller was an early nineteenth-century Scottish geologist, palaeontologist, folklorist, and evangelist, whose father had been a shipmaster. Miller’s father disappeared at sea in 1807, when Miller was only five years old, and was later pronounced dead. In his book My Schools and School Masters (published in 1854), Miller recalled how he:

‘used to climb day after day a grassy protuberance off the old coast-line immediately behind my mother’s house, and to look wistfully out long after everyone else had ceased to hope for the sloop with the two stripes of white and two square top-sails [of my father’s ship that] I never saw’.

Smetham added this quote to his etching of Hugh Miller and captured Miller’s sense of wistful longing in his etching and painting. This suggests that Smetham was drawn to this story because it provided him with an opportunity to visually capture all that Miller lost when his father died. This would have been particularly poignant for Smetham, who suffered his own personal sadness—to the point of significant mental distress—after the death of his oldest brother in 1842, which only began to improve after a spiritual encounter he had while attending his father’s death bed in 1847.

Finally, Smetham’s art provides deep, emotional, and extremely intimate insights into his mental health. Paintings such as ‘Thoughts too deep for tears‘ (1844), which he painted several years after the death of his older brother, brim with emotional turmoil and pathos.

These themes and more are explored in the Pre-Raphaelite Outsider: James Smetham (1821-1889) exhibition, which is open daily and free to attend at Bewdley Museum from 10am – 4pm until 29 October 2023.

In addition to the in-person exhibition, you can find out more about Smetham and his art by exploring the accompanying material on the Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History’s section of the Bloomberg Connect App (also accessible via the QR code below). This includes my introductory video to James Smetham’s Orrery of Personal Responsibility, which is also available on YouTube here.

Free Events

There is also a series of free events accompanying the exhibition.

- The team behind the exhibition will be speaking about the broader project the exhibition is part of, from 17.30 on 11 October 2023 as part of the IHR’s People, Place and Community seminar series. You can find more information about this event and register to attend here.

- From 11-12.30 on Saturday the 14 October 2023, I will be running a free interactive art workshop with Sarah Middleton, specifically reflecting on James Smetham’s Orrery of Personal Responsibility. You can find more information about this event and register to attend here.

- On 18 October 2023, Christiana Payne will be speaking in Bewdley Guildhall from 14.00-15.30 about Smetham’s relationships with Pre-Raphaelitism. You can find more information about this event and register to attend here.