This blog post was written by Justin Colson, Senior Lecturer in Urban and Digital History in the IHR’s Centre for the History of People, Place and Community (CHPPC).

Some decisions can have momentous tangible impacts upon where we live: our collective memories, the stories we tell about our communities, and local sense of place. Monastic ruins, or even the shadows left by their removal, shape many of our towns, villages, and high streets to this day, both in material traces and in local traditions and pride.

The story of the Dissolution of the Monasteries is conventionally told through the lens of Henry VIII and his advisors, or of the Priors and Abbots and their capitulation, or of resistance. But the story doesn’t end there.

What about the everyday people whose lives, and places, were transformed by the closure of the monastic institutions that had shaped not only the spiritual, but often the economic, lives of their communities? What about the lay-brothers, servants, butchers, and brewers who had built their lives around their local monasteries? What about the labourers, the masons, the carpenters, and carters, who were called upon to physically reshape, reuse, and recycle the fabric of monastic buildings? And what about the people over the centuries, and today, whose homes and built environment were fashioned from the reused and remade materials of the monasteries? A new IHR project, in collaboration with Historic England and other heritage and community partners, has been exploring ways of answering these questions.

One way to get closer to the experience of these communities is to shift the focus of study to literally look at the dissolution from ‘street-level’. What evidence can be found for the process of reuse and adaptation of each religious house: from the documentary archive, from archaeology, or from the built environment today? Equally importantly, by looking comparatively across many such histories, what can explain different patterns of reuse in different areas? And how is the impact of that reuse and adaptation still felt today?

During the summer of 2023 the IHR’s Centre for the History of People, Place and Community has run a programme of exploratory research and events on this topic. One of our starting points has been the wealth of research on individual monastic houses embodied in the Victoria County History: the majority of English counties have a VCH ‘Volume 2’ covering monastic houses, all of which are available on British History Online, but which are sadly little-known and under-used. Despite being often over a hundred years old, they are built upon invaluable archival research, and provide an unparalleled survey. To make this treasure-trove of monastic research more accessible, our project intern, Gillian Hollebone, has been busy adding links to virtually all articles on monastic houses from all counties to Wikidata (e.g. Dunstable Priory), which will be an important first step to building richer resources and maps to bring resources and sources together for researchers.

On 19th July 2023 Dr Justin Colson convened a research scoping and directions workshop. Around 30 experts from diverse fields, from archivists and historians, to buildings and landscape archaeologists, and community trusts, public engagement specialists and artists, met to discuss potential and priorities for research on the material history of the Dissolution. We identified several key areas to develop in research as we progress this area of work: from the potential of the Court of Augmentations Ministers’ Accounts in the National Archives, to the need for a conceptual and practical framework for the study of reused monastic building materials, and the power of placing communities at the heart of telling the story of why their places look the way they do today.

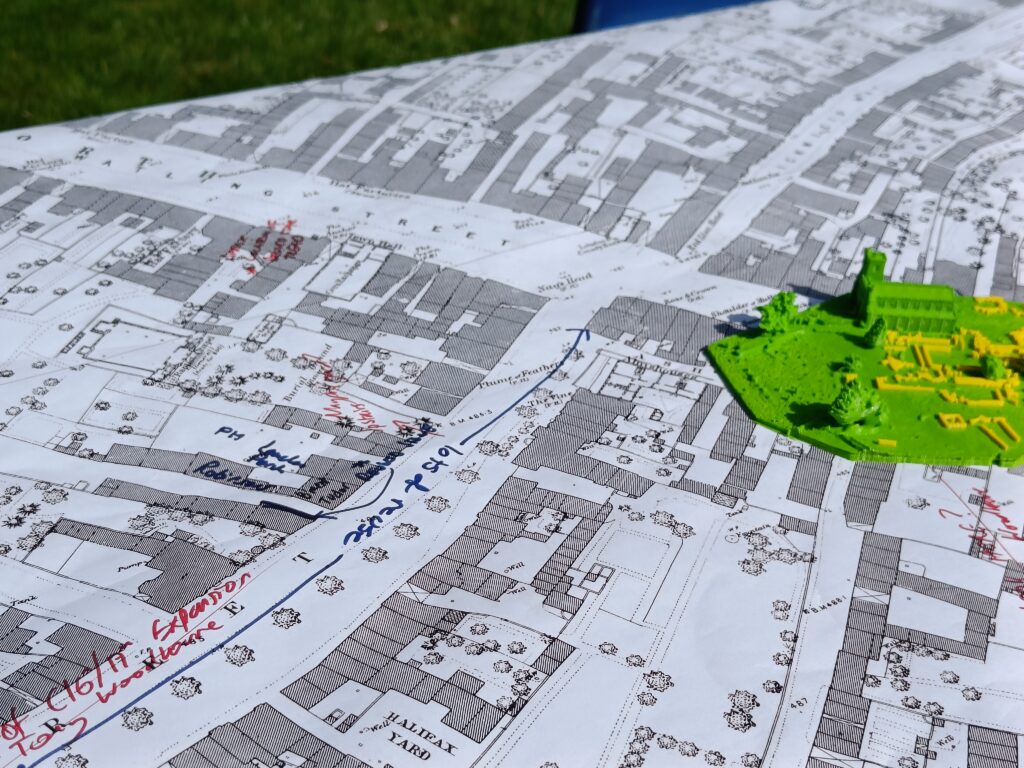

We also joined Historic England at Dunstable Town Council’s ‘Around the World’ festival, in connection with the Council for British Archaeology’s Festival of Archaeology, on Saturday 29th July to try out engaging with local communities on these questions. There was huge enthusiasm for sharing the hidden places where fragments of Dunstable Priory could be found: from upstairs in a Pilates studio to the cellar of an estate agent’s office. We even helped one neighbour of the Priory understand why her garden was so much more fertile than her other neighbours: her garden was located on the priors’ cemetery! Tracing these snippets of material evidence, even informally, began to reveal the significance of the Priory materials in the growth of the town—and particularly West Street—during the mid to later sixteenth century. Having seen this potential, we hope to be able to repeat this kind of community-led research to make sense of monastic reuse all over England and Wales!

The CHPPC is continuing to work with partners, including Historic England, and the Victoria County History community, to develop this research agenda. Justin Colson would love to hear from communities and researchers who would like to be involved.