In this blog post, Dr Ben Guy reflects on his recent appointment as the Bibliography of British and Irish History (BBIH) section editor for medieval Wales, drawing attention to the importance of the BBIH for providing coherence to the historical subject of ‘Medieval Wales’ and for enabling interdisciplinary study between history and allied subjects.

It was a pleasure to join the BBIH in September 2022 as the section editor for Medieval Wales. Projects such as the BBIH are essential for maintaining the coherence of broad historical fields of study, which can otherwise so easily become siloed and inward-looking. The powerful searching capability of the BBIH effectively draws together the subject areas represented by the sections, and serves as a healthy reminder of the diversity of research being undertaken within individual subject areas.

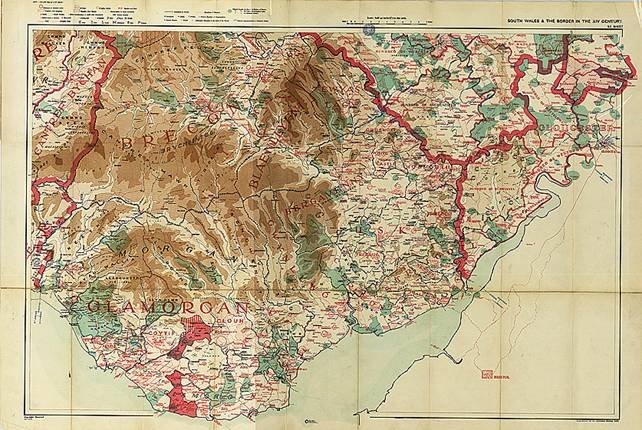

This is certainly true of the section for medieval Wales. This section concerns a relatively small geographical space, yet it takes in a thousand-year time-span, approximately from the end of Roman imperial governance in Britain to the Tudor era. Thankfully, this mirrors the nature of much of my research work. Since I often find myself tracing the development of textual sources (such as genealogies or chronicles) over long periods of time, I have found it necessary to have a good working knowledge of rather diverse periods of history: the age of Viking invasion and Welsh dynastic consolidation in the 9th century was really quite different from the ‘colonial’ Wales of the 14th century. It can sometimes prove challenging to maintain command of the various topics that together comprise the diffuse historiography of medieval Wales, but the BBIH eases this challenge significantly.

During my academic career, I have often found myself caught between the disciplines of ‘history’ and ‘literature’, to the extent that the precise distinction between the two within my areas of expertise can be difficult to define exactly. There are several reasons for this. At heart, I am an early medievalist, used to dealing with a time period for which source material is exiguous and obtuse and needs to be scrutinised minutely under the full glare of New Historicist literary criticism. Any difference between ‘discipline’ in this arena is really one between the questions asked of the same body of material, though to proceed effectively one needs to be aware of the questions that everyone else is asking too, whether historical or literary.

Another reason is that my main area of study is medieval Wales, especially between the 9th and 13th centuries. For this period, a significant proportion of the potential source material is written in the vernacular and exists as part of various literary discourses; nevertheless, when properly understood, such sources can be highly revealing in relation to a range of historical questions, especially those of a political and cultural nature.

These factors are both at play with the body of texts that I studied in my 2020 monograph: namely, the genealogical texts written in Wales between the 9th and 15th centuries, which in the past have managed to escape both historical and literary criticism. In fact, the genealogies can only be understood when subjected to multiple lines of questioning. They are a literary form existing in an interconnected literary-cultural space, but they overtly take contemporary politics as their primary subject matter.

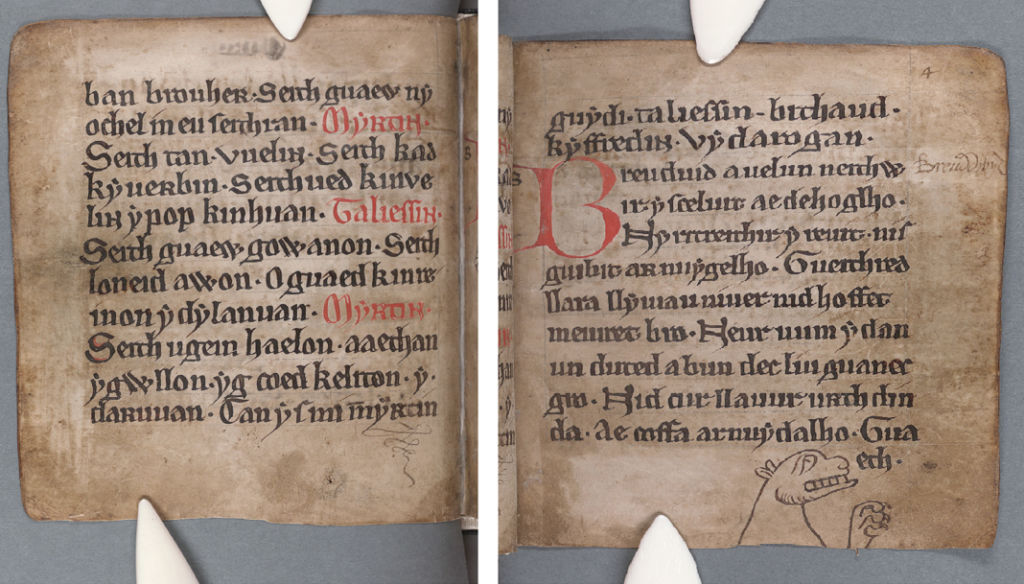

Similar circumstances obtain in the project that currently occupies me in Cardiff University. The purpose of the project is to create a new online edition of all the Welsh poetry in the voice of the ‘Merlin’ character that was composed up to the 18th century. I am responsible for the earlier material, most of which was probably composed in the 12th and 13th centuries. The character of Merlin, the famous wizard of Arthurian romance, was based originally on a Welsh legendary character called ‘Myrddin’, who notionally lived in the 6th century and whose primary role in early Welsh literature was that of the secular prophet par excellence. During the Middle Ages and beyond, Welsh poetry in the voice of the prophet Myrddin continued to be composed and became a useful medium for expressing anxieties about contemporary political affairs, or about the eschatological future of Christian time. Consequently, the poetry is speckled with allusions to the activities of Welsh princes and English kings, throwing an interesting light on perceptions of worldly affairs at that time. The poetry also agonises over the unravelling of social mores that was thought to presage the onset of Judgement Day, revealing much about how the maintenance of certain social relationships underpinned the sense of societal security for many contemporaries. Here again are literary texts that need to be understood in historical context, and which can conversely illuminate aspects of the past that would otherwise be hidden from our view.

I therefore approach my work for the BBIH in the spirit of interdisciplinarity and inclusivity. Projects like the BBIH should not merely bind together historical fields of study, but also act as a gateway between the discipline of history and other allied subjects. If I have reason to ask, as the medieval Myrddin poetry prompts me to do on a daily basis, questions like ‘how was William II’s taxation policy perceived?’, or ‘how was clothing linked to social hierarchy?’, or ‘would clearing forest to make way for corn-growing in 12th-century Wales be a good or bad thing?’, the BBIH can provide the first port of call. Hopefully, the result will prove illuminating for future scholars who read the poetry, whether they bring historical or literary questions to it.

Dr Ben Guy is a Research Associate in Cardiff University, working on the AHRC-funded project ‘An Edition of the Welsh Merlin Poetry’. He specialises in the study of texts and manuscripts from medieval Wales, and is the author of Medieval Welsh Genealogy: An Introduction and Textual Study (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2020). A review of this book can be read in the IHR’s Reviews in History here.