The IHR’s Centre for the History of People, Place and Community recently published the findings of a project on ‘Creative Repurposing and Levelling Up: History, Heritage and Urban Renewal’: both a website featuring case studies, and a policy paper for History & Policy. We’re delighted to publish here three other case studies on the repurposing of urban heritage, offered by authors Thomas Chambers and Richard Williamson.

Repurposing Gasholders in the Granton Waterfront Project

Thomas Chambers

A post on social media by the journalist Aaron Bastani recently caught my eye and made me consider the potential of seemingly unremarkable industrial architecture in creative repurposing projects. Replies to his tweet about the “historic vandalism” of past regeneration projects illuminate how industrial architecture can become iconic markers of identity and place. Among other comments lamenting the destruction of neo-classical buildings and historic town centres, two users included images of gasholders as examples of the destruction of local built heritage. Although never having had a civic function, or even being publicly accessible, such gasholders can become important landmarks of local identity; a reminder of industrial heritage. In the 1997 British film Shooting Fish the vision of the gasholder played a prominent visual and narrative role where the structures could be read as a metaphor for suburbia and transformation.

As part of the Granton Waterfront project, to redevelop the former industrial suburb of Edinburgh into a coastal satellite of Scotland’s capital, a disused gasholder forms a central feature of the plan for the site. The project is the largest redevelopment of its type planned in Scotland and is projected to deliver over twelve-thousand affordable homes and sixteen-thousand jobs. Granton Waterfront is designed to be a sustainable development with a focus on community and place-making. This means construction will incorporate energy saving measures, net zero-carbon homes, cycling provision, new green and public spaces, alongside new health, cultural and educational centres. The geographical position of the defunct gasholder within the regeneration means it will loom prominent over the new town as a creative repurposing scheme financed by the governments Levelling Up Fund.

The Granton gasholder was built between 1892-1902 as part of a new gas works built to supply the increasing energy demands of nearby Edinburgh. It was eventually taken out of use, becoming defunct with the discovery of North-sea gas, and sat disused along with five-hundred other gasholders across Britain. At the start of the century the National Grid began the process of selling off their unused sites for redevelopment. For the Granton site the gasholder is a key part of its redevelopment providing public space and functioning as a key pedestrian and cyclist route through the site. The structure is envisaged as a prominent identity and place-maker, acting as a catalyst for transformation. Local heritage is seen as a crucial way of making the new development a sustainable community. As a striking example of local heritage the gasholder has been lit up as part of recent festivals. This will now become a permanent feature as the structure will be transformed into a green public space for leisure activities and events.

While the gasholder is envisaged as an integral part of a green development it currently sits on a large brownfield site. Such sites incorporate mosaic habitats and are increasingly recognised as important wildlife habitats for rare species. The greening of brownfield land is seen as a wholly positive element within the Granton plans; yet their potential role as environmentally beneficial spaces within the development is left unconsidered. However overall, as part of the vision for creating a sustainable community identity, the creative repurposing of the Granton gasholder will be an inventive and positive transformation of local heritage.

Thomas Chambers is an independent researcher whose interests cover the modern history of the built environment and twentieth-century subcultures. He has written about the emergence of early graffiti in the Dutch and Spanish punk cultures, documented WWII ghost signs in London, and most recently has researched a social history of trainspotting.

31 Commercial Road, Gloucester

Richard Owen

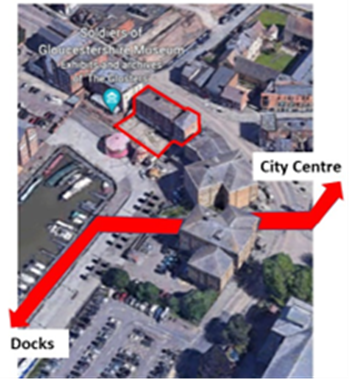

A developer, Ladybellegate properties, recently announced the first occupiers of a scheme, to be called the ‘Food Dock’, on the edge of the historic docks in Gloucester. The building in question has been vacant for at least 10 years; it is listed Grade II, and has a two storey frontage onto Commercial Road. At the rear, on its south side, it is a four-storey building; the ‘cellars’ at the lower two levels must originally have had uses related to the adjacent quay of the ‘barge arm’ section of the docks. The building is close to, but not on, the pedestrian desire line between Gloucester Quays and the city centre, and, to the west, is immediately adjacent to the ‘Soldiers of Gloucestershire’ museum. Considerable investment was attracted to the area, especially with the creation of the ‘Gloucester Quays’ shopping centre, between 2006 and 2013, when the GHURC, worked as a ‘go between’ between the city council, SWRDA and developers. The regeneration was awarded a Planning excellence award by the RTPI in 2013.

With the benefit of hindsight, it can be seen that GHURC and its partners managed to get a number of key ‘pieces of the jigsaw’ in place which have led, 9 years later, to the redevelopment of No 31 Commercial Road.

- The community, including public sector bodies were persuaded that the centre of Gloucester and specifically the Docks had a future.

- A strategy spelling out how that could happen was prepared and agreed.

- The ‘powers that be’ were persuaded that the redevelopment of the Quays (to the south of the Docks) for retail uses would not represent a threat to the historic city centre. The work that went into this persuasion included pedestrian movement studies and the use of hard landscaping, grant aided building improvements, signage and artworks to improve the route.

- Events were used to generate footfall and a change of attitudes in the docks area. The Tall Ships festival, started by GHURC, and, pre-covid, held biannually, attracted over 100,000 people to the area over the course of a May weekend.

- The development of the Quays was very successful, and included a number of units selling food and drink.

- When GHURC’s funding ended in 2013, the policy approach was continued by the City council.

I suggest that the development wouldn’t have taken place at all without the certainty given by points 1-6 above.

It’s impossible to know whether the redevelopment of No 31 Commercial Road could have taken place any earlier. The pandemic must have lost two years: planning consent was granted early in 2019. The company undertaking the scheme was established in 2015, and they announced the acquisition of the site in 2016.Much of the time between 2013, when GHURC ceased to exist and the marketing of the site will have been taken up with local government inertia. But the delay did allow developers to be assured of the commercial potential of the site.

The Clutch Clinic, Gloucester

Richard Owen

In the centre of Gloucester are the remains of Blackfriars Priory; dating from 1240, in the ownership of English Heritage, but until about 2009 known only to enthusiasts. The Gloucester Heritage URC was established to bring renewed life to the City Centre, and one of its target areas was Blackfriars; they worked with EH and the City Council to open the Priory as a very successful venue for weddings, conferences and concerts.

The priory buildings needed ‘improvements’: access to toilets, fire exits etc. It was planned that some of these could be provided in the re-development of an adjacent site, known locally as the ‘Clutch Clinic’, from its last ‘car repair’ use.

One of the Secondary Schools in Gloucester had the vision for the development of a ‘Language immersion centre’ where intensive teaching could take place; they bid for funding from the government, and £5 million was allocated. With encouragement from GHURC, the ‘Clutch Clinic’ was chosen as the site.

The first step was to record what stood on the site. GHURC had a strong and valued track record of involving the community in the development of projects, and with the help of Lisa Donel, the City Archaeologist, we assembled a team of 10 volunteers, who worked through the winter of 2011 to record both the physical structure and to research its history. They did a very good job; their report was accepted as an exemplar by English Heritage, who of course owned all the adjacent Priory buildings, and who were keenly interested in the development of the site.

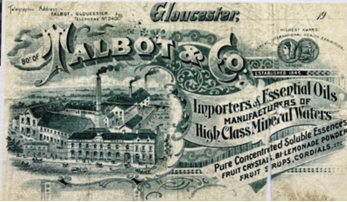

The Clutch Clinic had previously been a general garage; a bit like a children’s toy with a road loop within the building that allowed cars in on a one way basis. Before that it had been a Victorian ‘Mineral Water Factory’ (carbonating spring water and doing well in an age of temperance). The garage owners left the upper floor of the Mineral Water factory in place and simply punched archways in the ground floor to give car access.

Before that again (pre 1858) the site was in residential use. The whole Priory had been bought by a local business man, Sir Thomas Bell, from the King at the time of the dissolution of the monasteries. He had converted the monastery church into his house, and made the rest of the Priory into a factory making hats. He apparently employed 300 people, which must have made it a very big establishment for the Sixteenth century.

The demolition contractors did their work, and then the archaeologists moved in. We were able to install a viewing platform and arrange public access so that the history of the site could be explained. That history extended back to the Roman period; the site is just inside the Roman City Wall, traces of which were found.

The actual redevelopment of the site for language teaching included toilets and a visitor centre to serve the Priory itself, and was completed in 2012.

Richard Owen has spent his career working in areas targeted for urban regeneration and renewal, including in South Wales and Gloucester. He has been involved with numerous development proposals, many involving listed buildings.