By Christine Evans Appleyard (MRes, IHR, 2019)

There can be few visitors to the IHR building in Senate House who have not stepped inside the Weston Common Room. Rather like the family kitchen, it is the natural gathering place for essential refuelling and informal get-togethers. While the Wohl Library can rightly claim to be the IHR’s engine room, the Common Room has arguably provided not only the fuel to ensure the smooth running of its occupants but a welcoming forum for networking and collaboration.

The IHR has always had a Common Room and wherever it has been, academics, researchers and students have always gravitated towards it. Those who attended the IHR’s opening event of Our Centenary last July (8 July 2021, online) may have been struck by the affection with Douglas Peers, Dean Emeritus of Arts University of Waterloo, Ontario, still holds for the IHR Common Room, many years after his graduation. In his opening address at Session Three of the conference, Peers spoke warmly of the sense of community generated by the IHR and attributed the successful completion of his PhD in part to the Common Room.

A visit to the IHR’s archives in the Wohl library shows that Peers’ opinion is far from rare: the records are littered with references to the significant role the Common Room has played over the decades in the lives of students, academics, and visiting historians, particularly those from overseas. Professor Franҫois Crouzet of the Institut d’Histoire, University of Paris-Sorbonne, who first visited the IHR in 1945, noted that his first port of call was always the Common Room, where he knew good company was to be found alongside the tea and biscuits. For Professor Walter L. Arnstein of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the IHR Common Room was not only where he met many eminent British academics during the 1950s but where a student alerted him to the presence of documents vital to his research and ultimately the publication that followed.

IHR Common Room as it looked in the 1970s / 1980s.

It was the vision of the IHR’s founder, A F Pollard, that the IHR would function as a clearing house for the exchange of ideas. Isolation, he believed, was ‘fatal to the comparative method which is the essence of historical inquiry and induction’. Pollard’s vision was soon realised. Research students from all over Britain, and students and staff from overseas universities, came to the IHR as a matter of course when they visited London. According to New York historian William D Rubinstein, the IHR became ‘the best club in London.’

In 1937, overseas visitors accounted for fifteen per cent of the IHR’s population. Lord Macmillan described these folk as ‘potential missionaries of British culture and thought and business’. Certainly, by the 1950s, the then IHR tea lady was doing her best to uphold contemporary British tearoom etiquette, providing spotless tables, china crockery and the ‘correct’ cutlery. Moreover, as many would have been familiar with in their school days, regulars knew they were expected to return their tea things promptly for washing up, and that anyone daring to put their feet up on the furniture would be severely reprimanded.

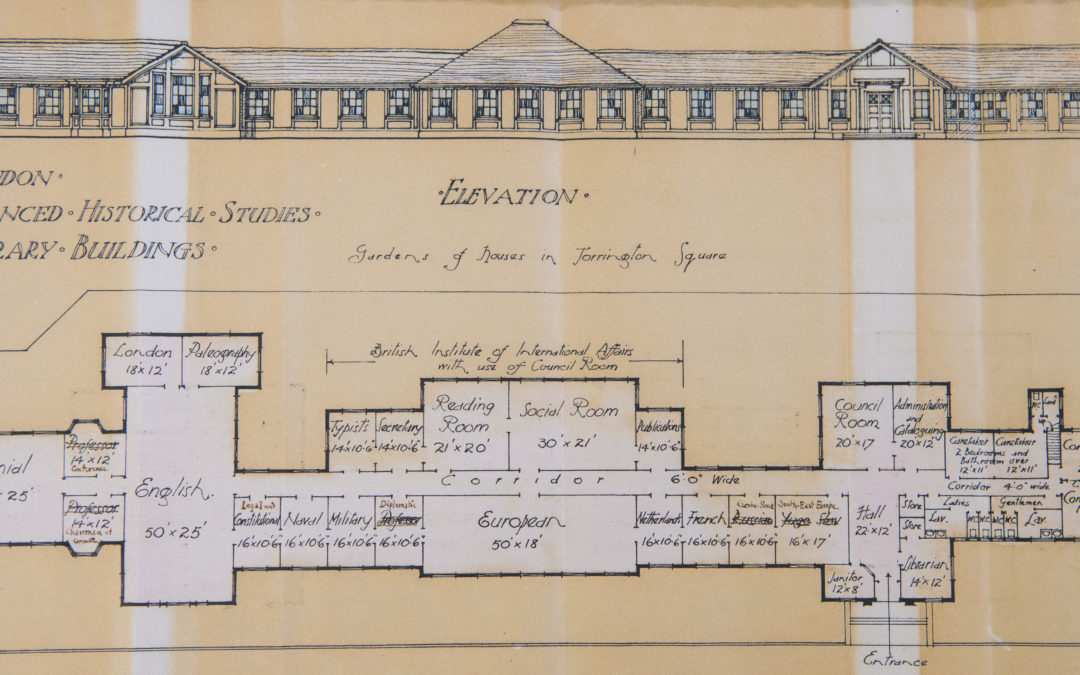

From the very beginning, through all the years of temporary accommodation in the Malet Street huts and before the current building was opened in 1948, a Common Room was considered an essential element of the IHR. Plans drawn up in 1920 for the IHR’s temporary accommodation in Malet Street showed not one but two Common Rooms—one smoking and the other non-smoking—to be used by both students and staff (see banner image at the top of this post). With the exception of the Council Room, where the Committees were held, the serving of tea was only permitted in the Common Room. The daily ritual of sharing tea at 4pm quickly became as much of a draw for students living in spartan accommodation as it did for historical researchers breaking off from their interrogation of the archives at the Public Record Office in Chancery Lane or at the British Museum Library. Former IHR Secretary and Librarian, Guy Parsloe (1927-1943) recalled how in the early 1920s the Institute came alive between 4pm and 5pm, when it was possible to purchase a pot of tea, two slices of bread and butter and a slice of cake for 6d.

Back in 1922, the Common Room boasted French windows leading into its own small garden, cared for by a Ladies Garden Committee, headed by Pollard’s wife, Katie. By 1933, with daily attendance reaching 40 people, the capacity of the Common Room was considered ‘woefully inadequate’. During the move to Senate House in 1938, it was recommended that the library would close but the Common Room, a useful place for meetings, would stay open. In December, the General Committee noted with approval that student friendships forged within the intimate confines of the Common Room had spawned a host of social events, including regular Sunday walks, theatre parties and Scottish dancing, while the annual Christmas party had become a recognised event in the IHR calendar. Such activities, they agreed, ‘contribute most effectively to the success of the Institute’s work by bringing together students from many countries and universities’.

Social activity came to a temporary halt during the war years, with the IHR initially closed to students from autumn term 1939 until the middle of January 1940, opening briefly until May. During this time, the Common Room was occupied by the government’s Ministry of Information with, intriguingly, a few places at tables reserved for members of the University. In September 1940, with no readers in the library, it was acknowledged for the first time that the Common Room had also become ‘superfluous’.

By 1946, the Common Room had reopened, but in June the traditional afternoon tea sessions came under threat by the introduction of post-war bread rationing. This calamity was skilfully avoided by members of the university maintenance staff, who unaccountably managed to acquire the necessary provisions, ensuring that ‘the IHR was able to preserve this valuable means of introducing students from many colleges and countries to one another’. In December 1946, the Common Room played host to the IHR’s annual Christmas party and, by 1947, all social activities had been reintroduced. With peacetime confidence coinciding with the opening of the IHR’s much-awaited permanent premises in Senate House, the Christmas party of 1947 saw the new Common Room ‘filled to overflowing’.

A leaflet published in February 1948 confirmed that Pollard’s vision was still in force:

The IHR has great influence in drawing together historians scattered among London’s many colleges. Many hold their post graduate seminars here and meet their colleagues in conference, library or common room.

In the late 1990s, the IHR’s Academic Secretary, Dr Steven Smith, wrote that if history students were asked to name an aspect of the Institute that they felt most warmly about it would likely be the Common Room. It may be purely coincidence that in 1994, the IHR obtained a private club license allowing it to serve alcohol! Following the IHR refurbishment in 2014, it was a natural choice for the Common Room to take centre stage for the rededication service, presided over by the University of London Chancellor, Her Royal Highness, the Princess Royal, and attended by 80 fellows, students, staff and Friends of the IHR.

IHR Weston Common room in the 2010s, prior to the Covid-19 closure.

The continuing uncertainty of the Covid 19 pandemic currently leaves the Common Room tea urn empty and switched off. Tables are spaced at two-metre intervals and open windows (providing a healthy draught ensure that in the depth of winter), mean that few linger over a brought-from-home sandwich for too long. One must hope this is a temporary state of affairs. While the advantages of online seminars, conferences, and meetings are not disputed, all historians know that often the most useful conversations take place once the formal business has been done. It’s difficult to do that in a virtual chat room, particularly for students and new researchers. Undoubtedly, the family-kitchen atmosphere of the IHR Common Room where, according to Joel Rosenthal, the ‘free-wheeling conversations and deal-making’ took place, remains just as important for historians in 2022 as it was in 1921.

Sources

IHR 1/1/1: IHR General Committee Meeting Minutes 1921-22; 1936-1950

IHR 1/2/5 – 1/2/7: Buildings Sub-Committee Minutes 1937; 1939

IHR 6/12/8: A Permanent Building for the Institute of Historical Research, leaflet c. 1934

IHR 6/12/11-13: ‘Institute of Historical Research. 31 May 1938′; ‘Institute of Historical of Historical Research. Report of IHR Committee (Nov.1946)’; ‘Institute of Historical Research. 15 February 1948′

IHR 9/1/11: University of London. Centre for Advanced Historical Studies. Proposed Temporary Building’ 1920

IHR 9/1/24: Memorandum and related papers concerning the future accommodation of the IHR, 1927-33

IHR 5/2/4: IHR Dining Club papers 1938-94; IHR Dining Club Committee Meeting 16 Jan 1939

Debra J. Birch and Joyce M. Horn, The History Laboratory: The Institute of Historical Research 1921-96, London 1996

Joel T. Rosenthal, ‘The First Decade of the Institute of Historical Research, University of London: The Archives of the 1920s’, Historical Reflections, 1.38.2012

Our Centenary Conference, IHR, 2021

Images courtesy of the IHR Archive

This blog is part of the IHR centenary project, From Jazz to Digital: exploring the student contribution at the IHR, 1921-2021.