In this fascinating blog, Dr. James Southern, a writer and researcher for the UK government, provides some startling insight into discriminatory policies which served as the basis of an official bar on gay men working as British diplomats that lasted until 1991.

The “Spotting a Homosexual Checklist”: Precarious Professional Identity in the Diplomatic Service

Diplomats, at least in the arcane realm of international politics, are putatively a personification of the nation states they represent. In the case of British diplomats, when an ambassador performs their duties overseas they officially do so on behalf not of the Prime Minister nor any elected official, but of the sovereign – the supposed spiritual and cultural embodiment of national identity.

At the same time, diplomats are professional civil servants. They are products of the socioeconomic and educational milieux of the nations they represent, and have to negotiate the entry criteria and institutional culture of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO).[1] The FCO determines the parameters and coordinates with which individuals must conform in order to do the representative work required of them.

Between 1967 and 1991, the projection of British diplomatic identity overseas and the environment from which individual diplomats were drawn at home were in conflict with one another. The 1967 Sexual Offences Act partially decriminalised same-sex acts between men: no longer did being “British” (in a legal sense) preclude being a gay man. Yet the FCO, which had hitherto adhered to a “don’t ask, don’t tell” maxim, was adamantly opposed to the employment of openly gay diplomats, wary of the link it assumed to exist between homosexuality, untrustworthiness and treachery.

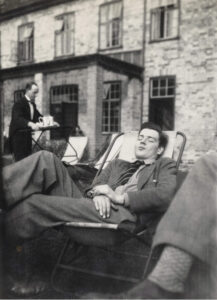

Picture of Guy Burgess

The FCO’s anxiety flowed from two sources. Firstly, a series of spy scandals in the 1950s involving gay men, most famously John Vassall and Guy Burgess (whose accomplice Donald MacLean also identified as bisexual), had been warped by frenzied tabloid journalism into a kind of moral panic to the extent that an official government report in 1963 declared that it ‘would normally regard homosexual behaviour … as creating a security risk.’[2] Secondly, the new ally on which Britain’s stability and status in the international arena now depended, the United States, was engaged at the time in its own homophobic purge – the so-called ‘Lavender Scare’ – in which, during the Eisenhower presidency alone, more than 400 American diplomats were forced out of the State Department for ‘real or imagined’ homosexuality.[3]

The FCO assumed that maintaining Britain’s integrity as a partner in the new Cold War depended on eradicating any association between homosexuality and diplomatic work – a task made much more difficult following the 1967 legislation. It embarked on a 24-year project to construct its entry criteria and internal culture around an imagined version of heteronormative masculine identity. It appointed a full-time ‘Homosexual Hunter’ to expel gay men from its ranks, and worked with the Civil Service Chief Medical Officer to devise what was termed a ‘Spotting a Homosexual Checklist’ to help with this task. The “Checklist” viewed today seems comical and shocking in equal measure:

Sleep (good, bad. Vivid dreamer).

Appetite (good, bad, indifferent. Interested in food; gourmet).

Eating habits

Smoking habits

Interest in Arts (Theatre, Music, Painting, Literature, Crafts, others)

Practice of arts (as above)

Interest and practice of sport (attainments)

History of:

Temper (judged by candidate himself, and by others)

Depression

Anxiety due to excessive worry

Loss of memory or Amnesia

Bed wetting

Nervous disorder of any sort

Long term use of medicines, tablets, tranquillisers

and sleeping drugs.

Drinking habits

Detailed amount of drink, type of drink consumed.

Emotional attachment to:

Mother

Father

Sister(s)

Brother(s)

Schoolfriends

Schoolmasters.

Tutors

Men friend(s)

Girl friend(s)

Fiance(e)(s)

Wife (wives)

Describe briefly (maximum 200 words each):

My three greatest emotional experiences.

Summary: A happy-go-lucky; meditating; slightly

depressed temperament; Independent – dependent.[4]

These policies served as the basis of an official bar on gay men working as British diplomats that lasted until 1991, when the then Prime Minister John Major cited ‘changing social attitudes’ as his justification for its abolition. Throughout that time, countless gay men (lesbianism was never the focus of the bar and was scarcely discussed) represented HM The Queen overseas while concealing fundamental aspects of their selves.

In my contribution to Heidi Egginton and Zoë Thomas’s Precarious Professionals: Gender Identities and Social Change in Modern Britain, I explore the construction of the FCO’s bar on homosexuality in the late 1960s. Using hitherto unseen files from the FCO archives at Hanslope Park, I show how the FCO constructed professional diplomatic identity around culturally and historically specific notions of heterosexuality and masculinity.

Diplomacy is a peculiar profession, requiring individuals to adhere to a peculiar model of technocratic competence and to perform their roles according to strictly-prescribed cultural “scripts”. Like the other chapters of Egginton and Thomas’ fascinating collection, my study aims to demonstrate the ways in which professional identity illuminates broader questions about social and cultural change in modern Britain.

Dr. James Southern is a writer and researcher for the UK government. He has published a book Diplomatic Identity in Postwar Britain (Routledge, 2021) and his chapter in Precarious Professionals: Gender, Identities and Social Change in Britain (University of London Press, 2021) titled, ‘The ‘spotting a homosexual checklist’: masculinity, homosexuality and the British Foreign Office, 1965–70’ is available free to read.

[1] This blog post uses nomenclature appropriate to the period which is its subject, when what is now called the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) had yet to merge with the Department for International Development and was still the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO).

[2] Lord Denning, Lord Denning’s Report, Cmnd 2152 (London, 1963), p. 190.

[3] See D. Johnson, The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government (London, 2004).

[4] Anon. to Anon., ‘The Spotting a Homosexual Checklist’, 28 March 1966