Ahead of the publication of his new book Simon Newman explores the African and South Asian people who sought to escape enslavement in seventeenth-century London.

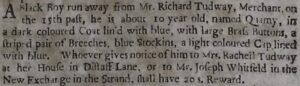

Advertisement, London Gazette, 2 March 1693.

His name was Quamy. His Akan day-name suggests that he came from the region of West Africa that we know today as Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, although it is possible he had been born and named in the English Caribbean. In 1693 he was in London, and we know about Quamy through the seventy-nine words of a notice published in the London Gazette on March 2nd 1693. Richard Tudway advertised that two weeks earlier Quamy had escaped from Tudway’s home on Distaff Lane. When he left Quamy was wearing the smart livery of a servant to a wealthy man: a lined coat with large brass buttons, striped breeches, blue stockings, and a blue-lined cap. The advertisement offered a reward of twenty shilling to anybody who brought Quamy or information about his whereabouts either to Tudway’s home or to his brother-in-law Joseph Whitfield in the New Exchange on the Strand. Finally, and perhaps most striking of all, this advertisement reveals that Quamy was just ten years old.

How had Quamy come to be in London? Tudway was a merchant and he was the co-owner of at least five ships which carried a total of more than twelve hundred enslaved Africans to England’s Caribbean and North American colonies. Three of these five voyages took enslaved Africans to Antigua, and the Tudway family owned plantations on that island which would remain in the family until the abolition of slavery. Perhaps Quamy had been aboard a slave ship and rather than disembarking in the colonies he had been brought back to London to serve the Tudways. Or perhaps Clement Tudway had sent Quamy from the family plantations in Antigua back to his parents Richard and Rachel in London. Whatever his route to London, this young boy was enslaved and the property of a man made wealthy by the trade in enslaved Africans and the sugar they raised and processed.

Between the 1650s and the turn of the eighteenth-century more than two hundred advertisements like this one appeared in London’s newspapers. They reveal something of London’s population of enslaved people during the years when England was developing and capitalizing on the Trans-Atlantic slave trade and colonial plantation slavery. Most were African but more than one-fifth were South Asian, and a small number may have been indigenous Americans. London’s freedom seekers were overwhelmingly male (84%) and ranging in age from 8 to 40 they were generally far younger than runaways in the colonies: over half were teenagers or younger.

Why were there so many enslaved people, many of them little more than children, in later seventeenth-century London? These were the years when racial slavery began to take root in England’s colonies. Between 1600 and 1650 we have records of fewer than seven thousand enslaved Africans arriving in England’s New World colonies, but between 1651 and 1700 that number rose to more than two hundred thousand. The Royal Adventurers and then the Royal African Company established trading posts on the West African coast from which they purchased enslaved Africans for shipment across the Atlantic, a trade Britain led by the early 18th century.

The profits of the slave trade and of sugar, tobacco and other crops transformed London, including the large amounts of West African gold turned into guinea coins. Enslaved African labour helped drive London’s emergence as a global city, and liveried enslaved boys became symbols of not just wealth but of connection to the drivers of that wealth.

Numerous portraits of the era show enslaved children as servants and attendants, including this portrait, the first of the Duchess of Portsmouth, Lady in Waiting to Queen Catherine and a mistress of Charles II.

Pierre Mignard, ‘Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth’, oil on canvas, 1682. The National Portrait Gallery.

Officials, merchants, slave ship captains, and planters all sent or brought back to Britain enslaved servants and attendants. The newspaper advertisements reveal that many were dressed as well as Quamy and as the children in these portraits. Others served as the cabin boys and servants of ship captains, while yet more worked for merchants and officials such as Samuel Pepys. African and South Asian servants trailing masters and mistresses around the capital, running errands or undertaking other work in such businesses as taverns, merchant stores and shipyards were far from an uncommon sight in London during the second half of the seventeenth century. Many were no doubt traumatized victims of the Middle Passage, and although the conditions of their enslavement in London were a world apart from slave trade ships or colonial plantations they were separated from family and community in an alien environment. As the surviving newspaper advertisements show, many chose to attempt escape.

We know little of what became of these freedom seekers. Those who were recaptured disappear with little archival trace, while any who successfully escaped did all they could to avoid attention. Only occasionally can we find hints of what happened to them. Fourteen-year old Champion, described in an advertisement as a ‘Negroe or Blackamore’ boy, escaped from his mistress on 17 September 1685, but six days later he was baptized at St Giles in the Fields, on the other side of the city from the address near the Tower of London where he could be returned. If still at liberty Champion may have been seeking to establish himself as a free Londoner and a member of the growing community of free Black and mixed-race Londoners who sought to control their own lives and destinies.

The advertisements reveal a network of merchants, ship-builders, ship captains and the financial elite who were intimately involved in racial slavery both abroad and at home. Often recaptured runaways could be returned to network members in businesses and financial institutions intimately linked to the rise of slavery, most prominently Lloyd’s coffee house. However benign slavery in London might appear, with some of the enslaved better dressed and perhaps fed than many of the city’s White servants, it was slavery nonetheless. Enslaved people were emblems of wealth, but they were also property. Some were branded and others were shackled with metal collars like the unnamed boy in the portrait above. And all were just one sale or voyage away from the savage charnel houses of England’s plantations. Attractive enslaved boys could grow into men who were less appealing as domestic servants. Sambo was an enslaved boy in Samuel Pepys’ household, but when he grew into a powerful young man he became too ‘dangerous to be longer continued in a sober family’, and Pepys contrived to have him kidnapped and taken aboard ship for transportation to and sale in the colonies. Slavery in London could all too easily be transformed into the hell of the colonial plantations.

Slavery was as real and present in London as it was in the colonies. So, too, was resistance by the enslaved, and London’s enslavers led the way in the creation of newspaper advertisements and a system and network for the recapture of freedom seekers. Runaway slave advertisements were invented in London, and these short notices reveal the significance of slavery in the metropole, as well as precious hints about the enslaved themselves.

Simon P. Newman (University of Glasgow, Emeritus, and Institute for Research in the Humanities, University of Wisconsin). Author of Freedom Seekers: escaping from slavery in Restoration London, to be published by the University of London Press, February 2022.