Dr Joe Chick arms himself with ‘A History of English Places’, the App for mobile devices developed by the Victoria County History (VCH) with Aimer Media. This time, he invites us to join him in Reading to explore the monastic influences still visible in the Berkshire town.

This week, my walk of historic sites using the A History of English Places app takes me to Reading in Berkshire. The app’s free version provides a history from Lewis’s Topgraphical Dictionary of England (1848) – the Victoria County History (VCH) produced its history of the borough as part of it’s third Berkshire volume, in 1923. It is available via British History Online or, linked to the app’s Ordnance Survey mapping, through the subscription version of the app.

This walk aims to recreate the town at a specific moment in time: the eve of the dissolution of the abbey. This was a dramatic moment in Reading’s history. Its abbot was one of only three who refused to surrender his house peacefully to Henry VIII. Consequently, like the last abbots of Glastonbury, and St John’s Abbey, Colchester, Abbot Hugh Faringdon was publicly hanged, drawn and quartered on 14 November 1539.

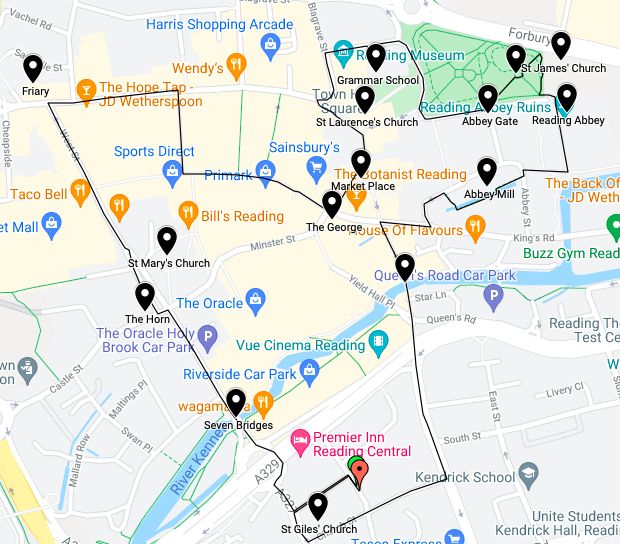

Joe’s walk around Reading. You can view it in more detail here.

Reading Abbey was refounded in the years 1121–5 by King Henry I, the son of William the Conqueror. It was a special place for the king. Despite dying in Normandy, he was ultimately buried in Reading. There are some gruesome descriptions of the state of his body when it arrived a month later. Upon its foundation, Henry I generously granted the abbey many assets, one of which was lordship over the entire the town of Reading. The abbey remained the dominant power in the town until its Dissolution 1539.

South of the River Kennet

Setting off from Saxon Court car park, I passed St Giles’ church. First mentioned in 1191, it was the poorest of Reading’s three medieval parishes. The current building has some 13th-century elements but was heavily rebuilt in 1872.

To reach the heart of the town, my route passed over the High Bridge. With the town wharf on the River Kennet’s south bank, goods arriving into medieval Reading crossed here to reach the market. With their ruinous state damaging trade, the bridges were heavily rebuilt in the 16th century and the present one was built in 1788.

Reading Abbey

In the Middle Ages, there were many more branches of the river running through Reading than today. Although almost hidden, the Holy Brook is one that still survives. Here lies the c.1200 remains of the Abbey Mill. The abbey once owned many mills, a powerful economic tool in an era when grinding one’s own grain was an essential activity for many inhabitants.

Archway in the ruins of Reading Abbey.

My walk passes through the recently restored remains of Reading Abbey itself. After the Dissolution the fabric of the abbey was repurposed and evidence of this can be found in St James’ church. When I first visited Reading, I assumed this to be a medieval church but it is, in fact, a Catholic church built in 1837–40 using abbey stone. It borders the Forbury, now a park but once a centre of trading and social activity within the abbey precinct. With the arrival of the abbey, annual fairs were held in the Forbury, along with the social activities of the neighbouring parish of St Laurence. I exited the Forbury through the Abbey Gate. One of several gates that once existed, this was an inner gateway separating the Forbury from the areas reserved for monks.

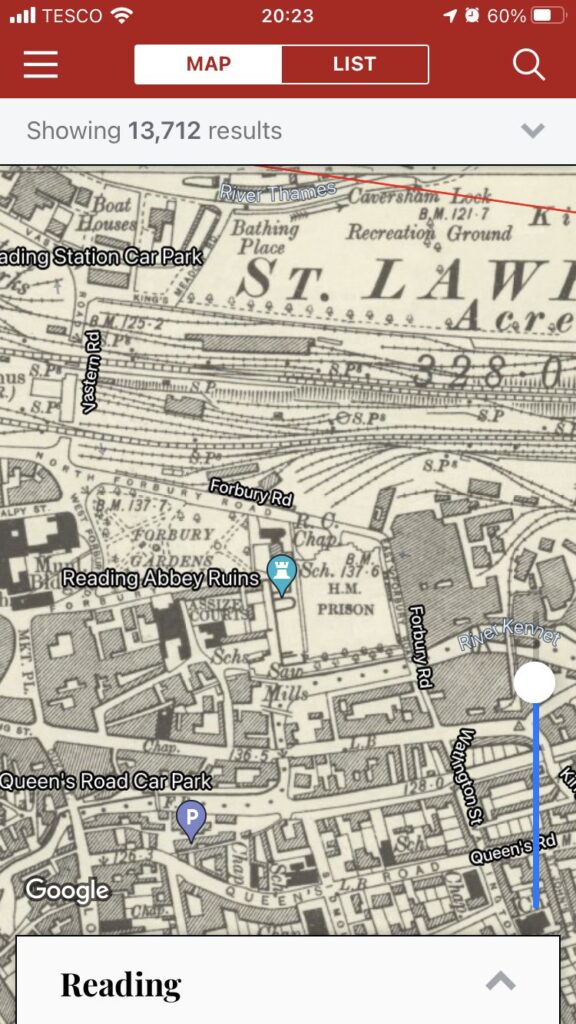

This screenshot from the ‘History of England’s Places’ app, shows the site of Reading Abbey, then occupied by Reading Gaol with St James Catholic church to the north.

The Town Centre

Many of Reading’s historic buildings are hidden from view and none more so than the grammar school. This building began as the abbey hospitium in 1196, before being converted into a school at the turn of the 16th century. From 1578, the upper floor served as a new town hall.

The Grammar School and former Hospitium

From the late 15th century, Reading had a prosperous cloth industry. St Laurence’s parish, home to many affluent clothiers, was the richest in the town. It also had the unusual feature of the boundary between the abbey precinct and the town running through the church.

Echoing this wealth, the marketplace, in the triangular shape characteristic of monastic towns, lies near to the church. The prosperity benefited The George, Reading’s oldest inn, first mentioned in 1423, and a high-status establishment.

The Old Town

To the west is one of England’s best-preserved friaries. When the Franciscans first arrived, the friars were relegated by the abbey to a flood-prone meadow and built this new site in 1285–1311. After the Dissolution, it became the town hall and is now Greyfriars church.

Greyfriar’s Church, Reading from the south west, as illustrated in VCH Berkshire vol. 3 and available via the app.

The area outside the former minster church of St Mary had been the town centre until the arrival of the abbey. Reading’s new lord forced the market to relocate closer to its precinct.

Completing the walk took me back over the River Kennet. Where a modern bridge now lies was once a series of medieval crossings known as the Seven Bridges, crossing the many branches of the river in this part of the town.

Reading Today

Reading’s visual appearance has changed dramatically since the dissolution of the abbey. It is rarely thought of as a historic town, with many remains of this era hidden by more modern buildings. In large part, this is due to Reading’s success and expansion in later eras. In the 19th century, beer, biscuits, bulbs and seeds, developed as key industries.

Throughout its history, London has been a major influence on Reading through the town’s place on the major routes west from the capital. Its railway link began with the opening of the Great Western Railway’s station in 1840, fuelling substantial growth. Links with London are still growing closer, with the upcoming Crossrail routes, connecting Berkshire directly to the centre of London, Essex, and Kent. Another recently designed route that visitors to Reading may enjoy is the Reading for Modern Pilgrims walk.

The town has also expanded to the north of the Thames to incorporate the Oxfordshire parish of Caversham. The latter parish, dependent on Reading for centuries, will soon be described in VCH Oxfordshire’s 20th volume. So it’s apt that my next and final walk takes me north west along the Thames valley to a town bursting with history: Oxford.

Dr Joe Chick studies English monastic towns and teaches medieval and early modern history at the University of Warwick. Joe currently holds a research internship with the IHR Centre for the History of People, Place and Community.

Get A History of English Places

The app allows you to see this history and the layered archaeology of the landscape in front of you with fresh eyes and the convenience of the modern world. Why not try it today? Download it here.