By Joe Chick

In my four previous walks, I’ve explored towns and cities in the east and Midlands. In this blog I’m exploring a city on the boundaries of the English Midlands and the south west, a port that dominated trade with France, Ireland and Wales throughout the Middle Ages and Early Modern periods, but whose more recent histories are often defined in relation to the legacies of the Atlantic slave trade.

Landscapes of settlement are constantly changing. The entries in the Victoria County History‘s app, A History of English Places not only guide us to the historic sites of a locality but highlight those now missing. Writing about Bristol in 1848, Samuel Lewis describes his memorial in All Saints church on Corn Street as ‘[a] magnificent monument… to the memory of Edward Colston, an eminent philanthropist, and a great benefactor to the city’.

Few would now use these words for the deputy governor of the Royal African Company who traded in enslaved people and memorials to him are being reassessed and removed. In June 2020, following the murder of George Floyd, a statue of 1895 was torn down and spent four days at the bottom of Bristol Harbour. It is now displayed in the M Shed museum, alongside placards from the protest and undoubtedly will play a role in how Bristol reflects on its past in the years to come. Windows commemorating Colston in Bristol Cathedral and the church of St Mary Redcliffe have also been removed.

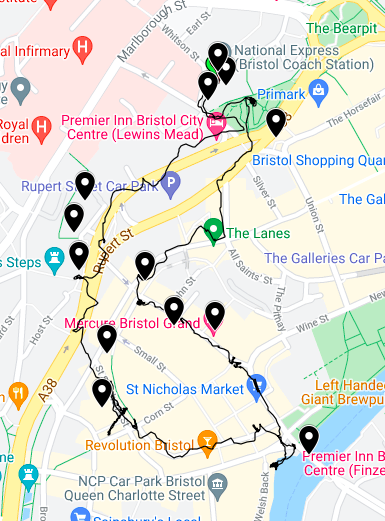

Joe’s walk around Bristol. You can view it in more detail here.

Exploring Bristol is a reminder of how the historic sites of a local area tell an incomplete story. Wealth is a crucial factor in erecting the buildings and statues that stand the test of time. As such, the most visible story is that of affluent white men. This week, I have been aided not only by the app but also the local expertise of Evan T. Jones of the University of Bristol, who took participants of the recent Fifteenth Century Conference on this walk.

Medieval Bristol

With access to the Severn Estuary, Bristol grew as a port many centuries before the slave trade. Prior to the modern era, wine was the key commodity. Those interested in the medieval town might also look at the 1480 map of Bristol, based on the account of the topographer, and Bristolian, William Worcestre, hot off the press from the Historic Towns Trust.

Our walk began at St James’ Priory, founded by the earl of Gloucester in the mid-12th century as a cell of the Benedictine Tewkesbury Abbey. The building that survives is the priory church and the park behind was its graveyard. Although not the home of plague pits, as once thought, it was used as an overspill graveyard by Bristol’s parishes at times of high mortality.

The walk took us to the 14th- and 15th-century church of St John the Baptist. Here we passed through one of the gates to the medieval town, which sits underneath the church tower. Bristol has the unusual feature of four churches that form part of the walls, the result of the limited space they offer for a town that grew considerably.

The Church of St John the Baptist, Bristol

The River and Quay

The 19th-century buildings on Broad Street are a testament to efforts to emulate London. The app’s entry, written in the mid-19th century, describes how the medieval guildhall had recently been replaced with a new one modelled on Westminster Palace. On the way to the river, we passed other buildings of the same era, like the 1860s Grand Hotel. At the river is Bristol Bridge, completed in 1768. Based on Westminster Bridge, it replaced a medieval structure lined with houses on the same site. Bristol originated north of the River Avon in Gloucestershire, but, spreading to the south, into Somerset, bridges were vital for its development ever since the medieval era.

St Stephen’s church, originating in the 14th century and rebuilt in 1470, was once beside the quays of the River Frome. Further along the quay area is Quay Head House, built in 1884 as new headquarters for the city’s poor relief efforts. Hidden down a side street is St Bartholomew’s Hospital. In 1240, this 12th-century town house was converted into a hospital before, in 1532, becoming the site of Bristol Grammar School until 1767. In its later life, it became a venue for theatrical performances.

St Bartholomew’s Hospital, Bristol

The app’s entry highlights sugar refineries as being a key part of Bristol’s economy. The most intact of these is the 18th-century Sugar House. Close by is another vestige of the 18th century: the Unitarian meeting house. Built in 1788–91, it could host 400 people and had a lecture room and schoolrooms added across the following century.

Abolition and Civil Rights

Edward Colston’s statue may have gone, but others remain. The walk passed the statue of Samuel Morley, a 19th-century Liberal MP who campaigned for the abolition of slavery. While a more appealing figure to most modern readers, it is still a reminder of how the built environment emphasises the deeds of white men.

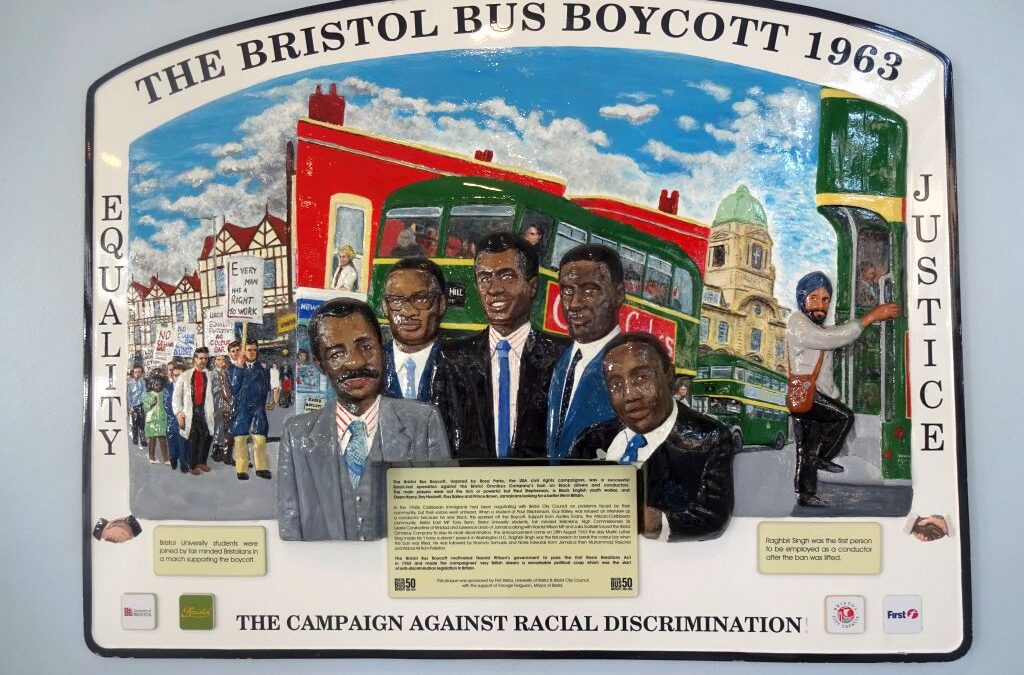

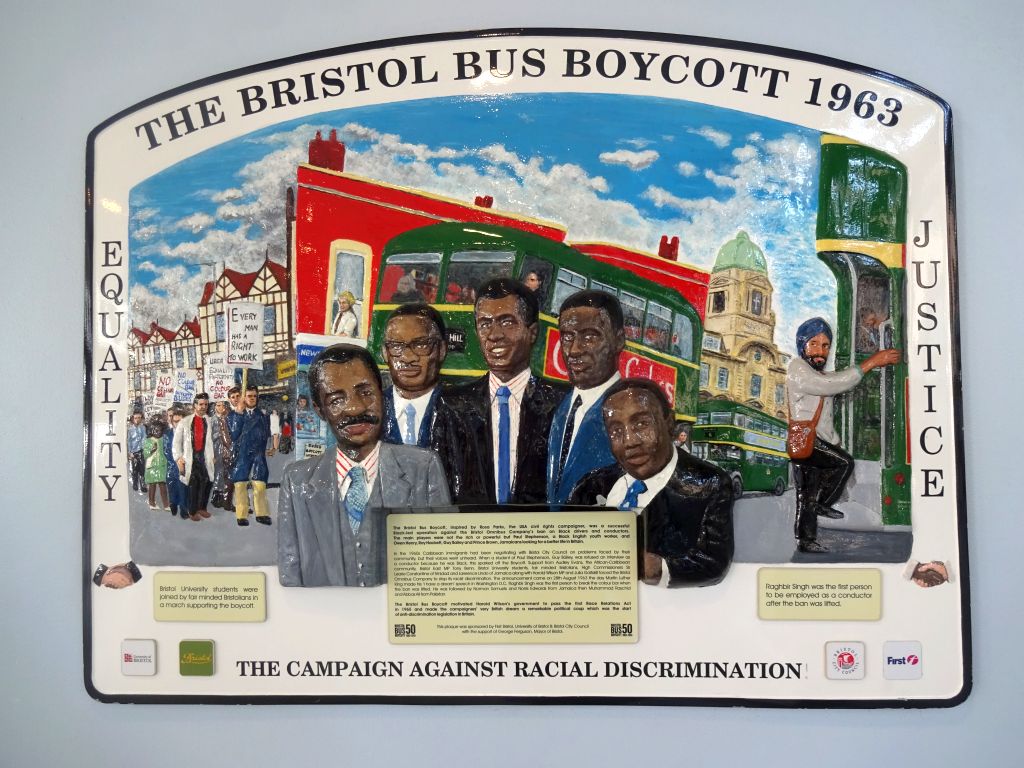

Exceptions to this are only just beginning to appear. After passing the 17th-century White Hart Inn, I finished with a visit to Bristol bus station. Not the most obvious historic site, but in 2014 a plaque was unveiled of Paul Stephenson, Owen Henry, Roy Hackett, Guy Bailey, and Prince Brown. Inspired by Rosa Parks, these four Jamaican men were leading figures in the Bristol bus boycott of 1963. The boycott was inspired by the refusal of the Bristol Omnibus Company to employ black or Asian bus crews and played its part in the Race Relations Act of 1965. Although not on this walking route, visitors to Bristol might also visit the statute of the playwright Alfred Fagon on the corner of Ashley Road and Grosvenor Road or the mural of Carmen Beckford, Bristol City Council’s first community development officer, at 38 St Nicholas Road.

Plaque at Bristol Bus Station commemorating the Bristol Bus Boycott of 1963

Next time, I’m heading to Reading.

Dr Joe Chick studies English monastic towns and teaches medieval and early modern history at the University of Warwick. Joe currently holds a research internship with the IHR Centre for the History of People, Place and Community.

Get ‘A History of English Places’

The app allows you to see this history and the layered archaeology of the landscape in front of you with fresh eyes and the convenience of the modern world. Why not try it today? Download it here.