Get involved in #VCHFutureHistoryproject. Your area 50 years from now

#VCHFutureHistory: Writing the Places We Want

The Victoria County History of England – a national project led from the IHR – is currently a partner in the AHRC-funded project Towns and the Cultural Economies of Recovery, with Professor Catherine Clarke as a Co-Investigator. In this piece, discover how local history can contribute to future place-making policy, and how you can get involved by imagining your place in 2050…

What do we want our towns – and our other places, from cities to villages – to be in the future? What kinds of tools and resources do we need to imagine those possible futures? Help us start a conversation with a crowdsourced #VCHFutureHistory of places across the UK. See below for ways you can get involved.

From Local History to Future History

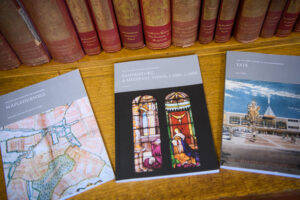

The Victoria County History (VCH) project has been writing the history of places in England for over 120 years. The VCH aims to complete authoritative, encyclopaedic histories of each county, from the earliest archaeological records to the present day. VCH studies cover topics from landscape and the built environment, to economic, religious and social history. Some VCH volumes were published over a century ago, while others are now in progress or planned for the future. The project was founded in 1899 and dedicated to Queen Victoria, which is how it gets its name. Today, the VCH produces two series of publications: the iconic Red Books of county history, as well as the VCH Shorts, which focus on single parishes and towns. The VCH is also a vast, diverse and lively community of historians, researchers and local groups, working on county histories across England.

The VCH plays a key role in the ‘Towns and the Cultural Economies of Recovery’ project, enabling us to connect with communities and mobilise VCH knowledge and networks in new ways. VCH research is also helping to frame current development challenges and opportunities in our four case-study towns. For example, Ken Crowe’s work on Southend gives a detailed account of the decline of tourism in the town in the later twentieth-century, and local government strategies to address this from 1964 onwards – from an early push towards light industry, to marina schemes in the 1970s and 1980s, to the ‘Towards 2001’ Local Plan and the Gateway to Southend seafront project.[1] For Darlington, the VCH account of the town up to the year 2000 provides a background to its social and economic character today, including the note that ‘The 20th century’s most radical efforts at transformation [of the town’s built environment] ultimately failed, thwarted variously by world war, lack of funds and public opposition, leaving the distinctive market town of Darlington to a generation more inclined to appreciate its historic assets’.[2]

The rich material produced by the VCH and other local history projects represents a hugely valuable resource for understanding the recent (and longer) pasts of our places, contextualising current challenges, and envisioning possible futures. The important inter-relationships between local histories and local futures are increasingly being recognised and embedded into planning and development strategies. A striking example is the Know Your Place project, developed in Bristol by Pete Insole, Principal Historic Environment Officer at Bristol City Council, initially as a resource to help inform planning decision-making with detail about the heritage – both tangible and intangible – of sites throughout the city. Now adopted by museums and local authorities across the south-west of England, and used by communities to share their stories, Know Your Place is a model for how history can be mobilised to enrich and shape our places for the future.

The VCH or Victoria County History itself is – unsurprisingly – focused more visibly on the past than the future. It is, after all, a history project! Where the future is present in VCH volumes, it’s more often by allusion – or even pointed omission or silence – rather than direct discussion. The 1912 Letchworth volume glances ahead towards the new Garden City, and there are mentions of urban and suburban development for places such as Rickmansworth. The account of the new town of Telford, written in 1985, looks forwards to later in that decade and even into the 1990s. Similarly, the VCH account of Crawley New Town (1987) ends by looking ahead to the projected outcomes of the West Sussex County Structure Plan, with its provision for new housing. The future of Bournemouth, one of our case-study towns in this research project, is suggested obliquely in the 1912 VCH account of Christchurch (then Hampshire), where the references to the creation of the new parishes of Christchurch East, Hurn, Southbourne, Pokesdown and Bournemouth (and then Highcliff(e)) and the ‘growing watering place’ of neighbouring Southbourne hint at the rapid expansion of the coastal resort town.[3]

Local and regional studies have traditionally focused on the past, but could offer enormous value as a resource – and practice – for thinking about the future, too. Could we pivot the huge research assets and expertise associated with local history into a resource for thinking about local futures? How could this deep expertise and knowledge about local places be mobilised to fill research gaps and inform policy-making? We’re experimenting with what might happen if we project local history – literally – into the future. What could happen if we write histories of our places, as we hope they will be in 2050, today? How could the #VCHFutureHistory initiative help to reveal our aspirations for our places and their futures?

Contexts

A number of overlapping government initiatives and funds provide the immediate context for the ‘Towns and the Cultural Economies of Recovery’ project, and our focus on the role of culture in successful and sustainable futures for our places. The Towns Fund, initially launched with a Prospectus in 2019, seeks to invest in towns to develop goals under the broad headings of ‘Urban regeneration, planning and land use’ (including ‘local cultural assets’), ‘Skills and enterprise structure’, and ‘Connectivity’. The March 2021 budget, with its Levelling Up Prospectus, offers further objectives and funding streams for the future of places, identifying three (inter-related) themes for the first round of ‘Levelling Up’ funding in 2021-22: ‘Transport investments’, ‘Regeneration and town centre investment’ and ‘Cultural investment’.

These funds focus on transformation and development for the future. But what do we imagine our future places will look like? What do we want them to be? And what resources, tools and capabilities do we need to envision those futures?

Futures

Thinking about the future is focused and formalised in many different practices and approaches, including in the field of Futures Studies, which has emerged over the past century. Thinking imaginatively about possible futures can be a valuable and productive tool for exploring our aspirations for our places and communities, and beginning a conversation about how we might get there. The influential Futures Studies theorist Ziauddin Sardar argues that

‘By thinking creatively about the future – what might happen, what we would like to happen, what we would have to do to ensure that certain things happen – we, as individuals and communities, can prepare for tomorrow and make more rational decisions on the kind of future we desire and make an effort to achieve it’ (Sardar, Future: All That Matters, 2013).

Thinking creatively about possible futures is not the same as making a forecast or prediction. The deliberate plurality of ‘Futures Studies’ moves away from emphasis on a single vision of the future – often dominated (or, in Sardar’s critique, ‘colonised’) by a focus on globalisation and technology – and opens up space for more diverse and inclusive perspectives, as well as potential for productive difference and discussion. Imagining possible futures, in this multi-vocal space, can be creative, collaborative, inventive, and even playful.

While thinking in terms of ‘future histories’ apparently moves historians into new temporal realms, history has long made use of imagination as a way into critical examination of hypotheses and possibilities. Counter-factual histories have offered tools for thought experiments, while speculative histories look both backwards and forwards to imagine alternative realities and open up new critical questions. While ‘future histories’ might initially seem more the realm of the novel or science-fiction than the historian, they represent, similarly, a space for testing out narratives or examining possible scenarios. If one role of the historian is in analysing, unpicking, but also making stories, then projecting that story-telling into the future is a valuable capability and asset. Thinking about futures is thinking with stories, and story-telling is a crucial tool both for imagining future scenarios and experimenting with narratives about how we get there.

Hope

In our #VCHFutureHistory experiment, we’re not just looking to possible futures, but we’re also deliberately aiming to centre hope and aspiration: inviting participants to write a future history which depicts their place as they hope it will be in 2050. We’re expecting diversity and difference: no individual’s hope for their place will be exactly the same as anyone else’s. But what’s the place of ‘hope’ in this micro-project, and in what ways can we think of hope as a tool and resource for thinking, policy and actions which point towards the future?

Jonathan Gross has written recently on the ‘practices of hope’ in cultural policy, arguing that hope is ‘central to political imagination’, while also acknowledging (in work pre-publication) that ‘hope is never politically neutral, and the content of collective hope is a key site of political struggle’. As an imaginative commitment to value-driven change, hope is a necessary and powerful engine for envisioning positive futures for our communities and places – but, as Gross highlights – always grounded in diverse experiences, subjectivities and desires, and potentially contested.

We could set hope alongside creativity, imagination and story-making (both looking backwards and forwards in history) as another of the capabilities necessary for positing and working towards good futures for ourselves and our places. #VCHFutureHistory is very small experiment in drawing these into focus together. Can our expressions of hopeful imagination for our places help to start a conversation about our towns, cities and villages in the future?

[1] Publication forthcoming as a VCH Short on Southend-on-Sea.

[2] Gillian Cookson, The Townscape of Darlington, with contributions by Christine M. Newman and Graham R. Potts (Victoria County History, Boydell & Brewer, 2003).

[3] With thanks to Adam Chapman, VCH Editor, for these references.

Invititation

Please join in our experiment on social media, using the hashtag #VCHFutureHistory (and don’t forget to include the name of your place, however big or small!).

You could write about the place where you live, or somewhere else in the UK where you have a particular connection. Perhaps you’ll take on the challenge of writing the micro-history of your place’s future in a single tweet – or maybe you’ll share a thread? If you’re stuck for a starting point, try asking yourself some ‘What if?’ questions about possible changes to your place, or search for #VCHFutureHistory to explore other examples. Remember, we’re keen to hear your hopeful future histories even if they sometimes disagree with each other.

Use the hashtag to view some of the #VCHFutureHistory which has been shared already – from a thread on Tonbridge by VCH Editor Dr Adam Chapman and a thread from @VCHGloucester, to a thread on an imagined future Bury St Edmunds, and a brilliantly provocative blog on Cambridge in 2050.

Thank you to the British Association for Local History, Historic England, local VCH County Trusts, and everyone who is supporting our #VCHFutureHistory experiment!