By Claudia Soares

Environment & History, essay no. 7

The next contributor to our ‘Environment & History’ series, Dr Claudia Soares, considers how histories of the environment, emotions, and welfare intersect, through the written experiences of poor and orphaned children sent to Britain’s settler colonies.

Soares shows how the language through which they described their new, often rural, environments, reflected their emotional experiences and ambitions, as well as the environmental racism and ecological imperialism of the British culture they were raised in. In so doing she pushes us to consider the importance of children in our collective relationship with nature, and the long history of that importance.

The next essay in the ‘Environment & History’ series will be published Wednesday 17 March 2021 with ‘The nectar of the forest: drinking water as an ecosystem service in early modern Augsburg and Europe today’.

At the set of the sun he puts away his tools and walks to the house. On his way he sees the full splendour of country life – the beautiful fragrance of the flowers, the birds’ evening song, the bleating of the sheep, the ring of the cowbell and the bleat of the calves. On looking around him, he sees, with mild wonder at the beautiful scenery, the maple groves casting their long shadows on the green fields and making you feel sorry for any lad who yearned for England after being in such a grand country as this. (Ups and Downs, Vol 7, Issue 1 (October, 1901) p. 28.)

So wrote Robert Whitlaw about his experience of migrating to Canada at the turn of the century. The account formed part of a letter written back to Barnardo’s, as an entry into their competition ‘A Day in My Life in Canada’, which was advertised in the institution’s periodical Ups and Downs, published for child migrants like Robert. His narrative centres on the sights and sounds of rural Manitoba: it describes in minute detail his fascination, joy, and wonder in the nature that surrounded him. Like other letters sent across the eighteenth, nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries by colonial settlers, it deliberately recalled the sublime English pastoral: Robert connected his past and present with the similarities and differences observed in the environment around him to the ‘old country’.

This device was particularly useful for the magazine too, given the publication’s objectives to settle young migrants in their new country, and highlight the advantages of emigration to other children in Barnardo’s residential homes. Robert’s testimony suggests an acute awareness of the homesickness and yearning that many of his peers undoubtedly felt, but concludes that ongoing grief about the old country was pitiful compared to what Canada offered. His letter depicted him delighting in farming, achieving success, and content, in a healthy, restorative, and beautiful local environment which may have been difficult for Robert to find in British industrial towns. Robert’s correspondence was not exceptional. Countless other migrant letters – some reprinted in periodicals such as Ups and Downs, others surviving in several welfare organisations’ archives – indicate that many children found their experiences of migration and settlement more positive than traditionally assumed.

Despite Robert’s motivation and purpose for writing, the letter offers insight into his experiences and feelings about his new country that are not often focused on in studies of child migration. Such work has tended to emphasise the loneliness, exploitation, and trauma experienced by thousands of poor young children shipped to Canada and left to fend for themselves with no ongoing support. Despite marketing emigration programmes as a path to better life chances and a thriving labour market, few migrants experienced substantial prosperity. Too often, they were simply sources of cheap labour. What migrants made of their experiences is often unheard: inspection reports – if completed at all – rarely placed significance or value on what children said or felt. Meanwhile, letters sent by children – often back to institutional staff – are problematic because of the purpose of their writing, and the unequal power dynamics in their relationship.

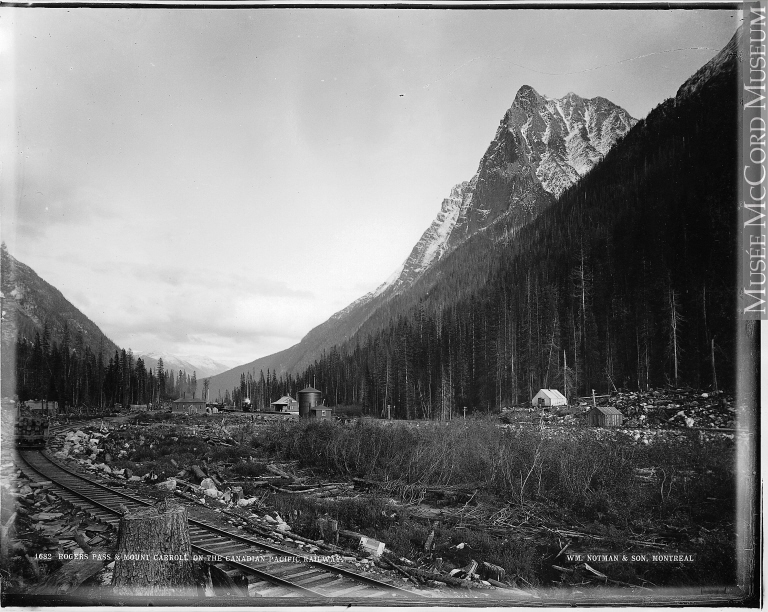

William McFarlane Notman, Rogers Pass and Mount Carroll on the C.P.R., B.C. Canada (1887). McCord Museum, VIEW-1682.

While historians have made extensive use of immigrant letters written by adults, scholars have only recently turned their attention to those penned by children. Additionally, there are only faint traces of the voices of poor migrants. As such, the poor child is doubly marginalised in the wider corpus of migration and settlement narratives. My previous work used the letters written by child migrants to reveal some of the more positive experiences of migration, and how children forged affective bonds with institutional staff. This adds greater balance and complexity to stories of welfare provision, which have tended to focus on both the sensational and negative; the story of what welfare institutions did to people, rather than how people individually and collectively experienced different forms of intervention and support.

The environmental is integral to understanding both the social and emotional histories of individuals: scholars have reminded us that human history has been shaped by environmental factors and forces, as well as non-human life forms. [1] My current research, part of a larger British Academy-funded project about welfare and emotions in Britain, Australia, and Canada, 1820-1930, brings this focus on the environmental to bear in unpicking the social and emotional history of migration among poor children. These child migrants were continually shaped by their environments and sought to shape the world around them, often in deliberate and specific ways. Their knowledge and feelings about their environments affected their experiences and engagement with their surroundings. Ideas about environment were also crucial to the ideologies of welfare institutions. Clare Hickman has shown how natural environments were used to manage and treat inmate populations, while other scholars have investigated the perpetual concern of institutional officials around the effects of certain environments on welfare, health, and character development. [2]

My work combines approaches from the history of the senses and the emotions, with environmental history at its most fundamental – the role and place of nature in human life. Where possible, I also highlight the active role of nature in the lives I study, and collect evidence of the natural world and non-human species affecting individual experiences, feelings, and actions. In bringing these subdisciplines in dialogue with each other my work does not seek to overturn the narratives of child migration as controversial or inhumane, or that migrants experienced extreme hardship and trauma. Its focus is not on evaluating these programmes, but instead, on centring the child’s voice to listen to and understand more carefully what they sensed and experienced, to recognise that it was varied, uneven, and often changing.

Like other colonial settlers, children corresponded in depth about their new environments: the climate, landscape, soil, vegetation, and wildlife frequently took centre stage in their letters. This is unsurprising: many children were transported from industrial urbanscapes to wholly foreign, rural settings. Their surroundings were entirely new and different, and letters talked at length about these novel and exciting differences in relation to the ‘old country’. Their knowledge about the imperial environment prior to arriving was shaped by representations of colonial life in the periodical press, which perpetuated environmental racism and ecological imperialism. [3] Children’s colonial literature emphasised the dangers of the natural world: unfamiliar, hostile wildernesses, with dangerous climates and predatory wildlife. Such representations promoted a sense of the exotic and of adventure. These environments offered little of the civilised and cultivated beauty of England, and instead, literature promoted the idea that settlers had battled, tamed, and overcome nature, and indigenous peoples. Some letters drew on ideas of exoticism and nature’s unruliness, but in many cases, migrants expressed their surprise and delight in finding a beautiful country that resembled England. Offering comparative references to their old country and writing about their new environments made them familiar and understandable, not only for letters’ recipients left behind at ‘home’, but also for their authors, who continually sought to make sense of their experiences.

William McFarlane Notman, Shuswap Lake on the C.P.R., near Sicamous, British Columbia, Canada 1889 (c.1902), McCord Museum N-0000.25.1056.

Historians have noted in passing the frequency with which migrants’ spoke of the natural environment or climate. [4] Descriptions of these environments highlighted children’s new-found sense of adventure and freedom. Given the increasingly rural lives these children had been trained for, many took a greater interest in the natural environment than before. The weather, climate, and wildlife were now everyday concerns for those tasked with growing crops, hunting, and tending livestock to earn a living. Their relationships with and understanding of nature shaped their ‘success’ in their work, but also their capacity to adapt to new routines and patterns of everyday life. Additionally, the ways in which migrants thought and spoke of their new environments were shaped by institutional ideologies, which emphasised the natural harmony of the rural over the degenerative urban environments from which many young migrants had been rescued. But for some, descriptions of weather and local environments were ceremonial and conventional forms of communication: filler in letters about monotonous, lonesome daily life.

Studying how migrants wrote about their environments, various themes emerge: ideas of home, belonging, identity, nostalgia and memory, kinship, comfort and intimacy, health and wellbeing, and dreams and ambitions. These can all be translated from their talk of the environment. The environment becomes shorthand for their emotions about their world and life.

Twelve-year-old Thomas Fragle’s letter offers a retrospective on how he imagined Canada prior to departing and his feelings on his arrival in 1897:

Before I left England, I was under the impression I was coming to a wild, desolate country, inhabited by a few white people and Indians. Upon my arrival at Quebec these thoughts left me, as I found a bracing climate and beautiful scenery, but, more than all, a nice, sociable people. (Barnardo’s Ups and Downs, Volume 4, 2, (January 1899), p. 61.)

Placing this narrative within the context of Thomas’s life events allows us to unpick his feelings and attitudes further. His vision of Canada was one shaped by a patchwork of information, which likely included colonial literature and knowledge gleaned from institutional staff and his peers. His idea of Canada as a bleak, unruly, and unwelcoming land with few ‘friends’ suggested his deeper feelings about recent experiences. The loss of his mother in the winter of 1896, followed by his father’s death in the summer, meant that Thomas was cast adrift in the world as an orphan. Admitted to Barnardo’s homes, he was quickly selected as a candidate for emigration: his impending relocation to a completely unfamiliar wilderness, thousands of miles from any remaining kin must have exacerbated feelings of being utterly alone in the world. But his letter suggests that contrary to his ideas about Canada, he was immediately arrested by its beauty, familiarity, and likeness to the ‘civilised’ old country. His description aptly aroused the senses, evoking a vision of a chilly, brisk climate contrasted with the warmth and friendliness he found in its inhabitants.

The comparative narratives of migrants, contrasting the new world with the old country, conveyed a repertoire of emotions: homesickness, grief, yearning, and nostalgia were sentiments felt strongly by many. Letters demonstrate just how bound up these feelings were with the landscape, detailing how children recalled and remembered the English landscape, as they grappled with understanding their new settings, and in turn, their place in the world. Henry Joseph Page evocatively wrote:

I like to work in the fields, for it is much more pleasanter than it is working in the dull city of London…it is more pleasant to see the rich fields of grain than it is to see the busy street and the crowds of working men rushing to their work…I like to work in the harvest fields, and to hear the sweet song of the birds as they fly to and fro, and to listen to the hum of the binder as it is cutting down the grain and making it into sheaves… (Barnardo’s Ups and Downs, Vol 4, 2 (January 1899), p. 62.)

Like Henry’s letters, other migrants talked about their environments in a particularly sensory manner – descriptions draw on sight, sound, smell, and the haptic – all of which helped to shape feelings about the old world and the new, and the individuals’ place within it. The extremes of temperatures encountered in Canada, for example, emphasised notions of adventure, of hardiness and adaptability, of isolation and remoteness, or of stifling oppression and monotony. Children often spoke of the smells of their new environments as being restorative for health and wellbeing: the environment was clean, fresh, and sanitary, inclined only to a little mild dampness, unlike the dirty smog, impurities and pollution of the industrial towns that had contributed to their ill health at home. Many remarked on how healthy and fit they were: ‘the climate quite agrees with me, I have not been sick a day…’ (Letter from Minnie M. Neville, Barnardo’s Ups and Downs, Vol 10, 1 (January 1904), p. 56.)

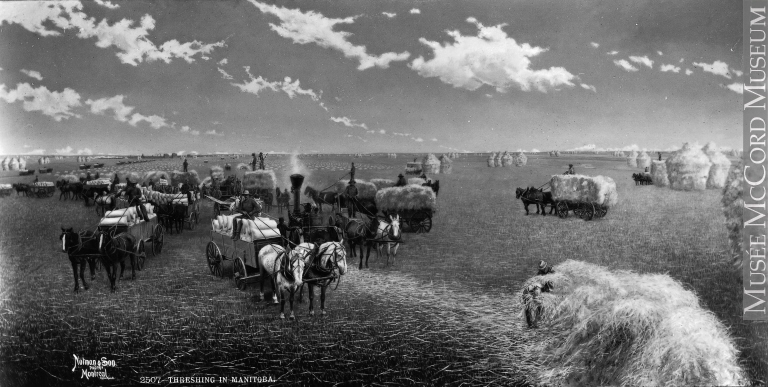

Wm Notman & Son, Threshing in Manitoba, c.1891. McCord Museum, VIEW-2507.

Other letters demonstrate the particular meanings migrants assigned to their environments, revealing how youths found comfort and solace in nature. Alice Weeks wrote about her affinity with the animals she cared for, who provided her with companionship, entertainment, and intimacy.

I like living on the farm very much; after living in the city all my life things seem very strange. When I first saw little chicks I nearly went crazy over them, and I always used to be peeping at them and calling them “such dear little things”. I have a little pet lamb too, which I feed with milk every day. He lives out in a field with three calves, and when he sees me comes running as fast as he can, and that is fast. (Barnardo’s Ups and Downs, Vol 8, 3 (July-August 1903), p. 58.)

The environment might also be bound up with newly realised ambitions of (re)making home: their dreams of taming and governing nature to yield crops, of making a homestead, and achieving freedom, independence, and prosperity.

When I leave here, if I ever do, I am going to be a farmer. As soon as I can get a place I’m going to put some fine buildings on it, so that my master and mistress can come and visit. I don’t think I could get into the hands of better people in the North West. Don’t think that I am telling any lies, because I am not…I guess I will make my home in Canada. I won’t go back to England again. You can get lots to eat out here. I did not think it was so good out here, but I have found it out now… I would rather be out in the field ploughing than in the streets selling newspapers. You get lots of fresh air in the fields; you ain’t breathing smoke all the time. You bet the farm is the place for me, not the streets…I think I will quit now, my fingers are getting tired. (Letter from William T. Eaton, Barnardo’s Ups and Downs, Vol 9, 2 (April 1903), p. 30.)

These published letters do pose methodological challenges: some may have been edited or censored prior to being printed in periodicals, while others might even be fictional. My efforts to trace original migrant letters in other archives have been frustrated by the institution’s full or partial anonymisation of correspondents. But the provision of authors’ full names in Ups and Downs has enabled me to undertake genealogical research to chart their life and movements in Canada and beyond, and to verify significant information contained within the magazines. Moreover, when children wrote to the institution they often wrote repeatedly: even from published letters, we can trace their movements and experiences over several years. The next stage of my research using institutional records will build a fuller picture of each child’s time in Barnardo’s homes and assess whether original correspondence survives within the archive. But even where original correspondence has not survived, these letters remain both significant and valuable in revealing how adults and children imagined colonial environments, their attitudes towards, and relationships with, the natural world in imperial settings. Indeed, these publications were part of a wider body of cultural products produced for child readers that framed colonial settlement in relation to the environment.

Studying child migrants’ correspondence about the environment, and representations of the natural world produced for children, has important implications for understanding present day issues. Recent, devastating events such as the Australian bushfires, Californian wildfires, and Covid-19 pandemic, force us to take stock of our individual and collective relationships with nature in the past, present, and future. They remind us of the important role children play in environmental issues: children have been pivotal in conservation movements and environmental activism. Throughout history, children have been intimately connected with the natural world: their appreciation of and relationships with nature, and their awareness of environmental issues has a much longer history that must be interrogated. [5]

Child migrant letters are thus a significant yet underused source in helping us unpick, among other things, this longer history of children’s engagement with the natural world. By combining approaches from sensory history, the history emotions, and environmental history, these sources offer the possibility of contributing to broader cultural and social histories of childhood, welfare, migration, and Empire in new ways. Histories of colonial settlings distinct from those told from the viewpoint of transnationally mobile, British middle-class families. There is a need to examine these sources with greater consideration to ideas of identity and national culture too: to better understand what Englishness and Empire building meant in child migrants’ minds, and how nostalgic sentiment for the rural was bound up with ideas of nationalism, modernity, and class.

These narratives might also provide new insight into issues about ecological imperialism, including the shaping of attitudes, feelings, and behaviours through representations of colonial environments in contemporary cultural products. But above all, they highlight the interdependent relationship between emotion and environment: individual and collective feelings about the natural world, and how these sentiments and environments shaped notions of selfhood, identity, and life trajectories more broadly.

References

- Emily O’Gorman and Andrea Gaynor, ‘More-Than-Human Histories’, Environmental History 25, no. 4 (October 2020): 711–735.

- Oliver Gibson, ‘Health, Environment and the Institutional Care of Children in Late Victorian London’ (Unpublished PhD thesis, Queen Mary University of London, 2017); Hester Barron, ‘Changing Conceptions of the “Poor Child”: The Children’s Country Holiday Fund, 1918–1939’, The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, 9, no. 1 (March 2016): 29–47; Keith Williams, ‘“A Way out of Our Troubles”: The Politics of Empire Settlement, 1900-1922’, in Emigrants and Empire: British Settlement in the Dominions Between the Wars, ed. Stephen Constantine (Manchester, 1990), 22–45; Elspeth Grant and Paul Sendziuk, ‘“Urban Degeneration and Rural Revitalisation” : The South Australian Government’s Youth Migration Scheme, 1913-14’, Australian Historical Studies, 41, no. 1 (2010): 75–89.

- Michelle J. Smith, ‘Transforming Narratives of Colonial Danger : Imagining the Environments of New Zealand and Australia in Children’s Literature, 1862-1899’, in Children, Childhood and Youth in the British World, ed. Simon Sleight and Shirleene Robinson (New York, 2015), 183–200.

- Moss et al., ‘Rethinking Child Welfare and Emigration Institutions, 1870–1914’; Fitzpatrick, Oceans of Consolation; Laura Ishiguro, Nothing to Write Home about: British Family Correspondence and the Settler Colonial Everyday in British Columbia (Vancouver, 2019).

- Frederick Stephen Milton, ‘Tiny Humanitarians? Children as Proactive Nature Conservationists in Late-Nineteenth Century Britain’, in Science in the Nursery: The Popularisation of Science in Britain and France, 1761-1901 (Newcastle, 2011), 91–107; Diana Donald, Women Against Cruelty: Protection of Animals in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Manchester, 2020).

Featured/title image Library and Archives Canada / PA-117285, Boy ploughing at Doctor Barnardo’s Industrial Farm ca.1900, Acc. No: 1972-020 NPC.

***

Dr Claudia Soares is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at Queen Mary University of London. Her current project ‘In Care and After Care: Emotions, Institutions, and Welfare in Britain, Australia, and Canada, c. 1830-1930’ takes a global look at children’s care at a time of rigorous policy development, and children’s experiences of those changes. A co-convenor of the IHR’s Life Cycles Seminar, her first monograph A Home from Home? Children and Social Care in Victorian and Edwardian Britain is under contract with Oxford University Press, and her most recent article, ‘Leaving the Victorian Children’s Institution: Aftercare, Friendship and Support‘ was published with the History Workshop Journal in 2019.