By Adam Chapman

What histories can we read in a landscape? How have people and communities been shaped by the places they occupy? Dr Adam Chapman, of the Centre for the History of People, Place and Community, and Editor of the Victoria County History (VCH) looks at what we can learn about how the post-war farming landscape shows its pasts and provided hints at its futures.

The Victoria County History takes place as the unit of historical enquiry and works on the premise that every place in England has a history worth recording, from the earliest times to the ever moving now. Much of England is still rural, even if most of the inhabitants of rural communities are not employed on the land today. So the sources for agricultural history are familiar to the VCH researcher. These are many and varied. The include Domesday Book (1086), manorial accounts and surveys, estate records and crop returns complied for the Ministry of Agriculture and its successors. Above all, there is the landscape itself and how farm land and farm buildings demonstrate the history of the exploitation of the land.

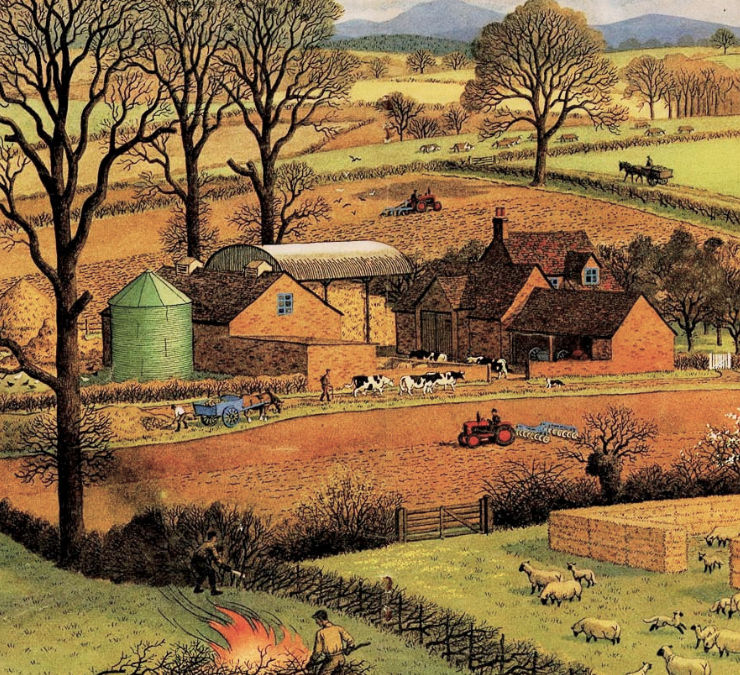

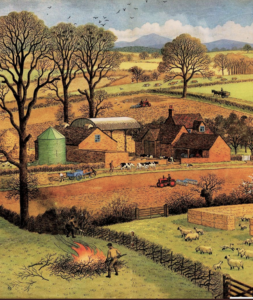

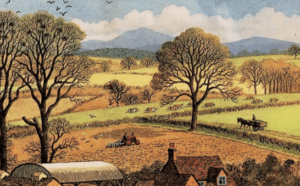

This blog draws on that research and examines the English farming landscape in the years after the Second World War as drawn by Ronald Lampitt, an artist best known for his work in the Ladybird series of children’s books. This precise landscape may never have existed – it could be Kent, but the distant mountains might stand for the Malvern hills – but the story told is a national one.

A Farm in February is the title of this ‘Picture to Talk About’, published in Treasure Magazine, 1963. But what Ronald Lampitt’s illustration does is to take a snapshot of a very particular point in the modernisation – and mechanisation – of British farming.

This is a winter landscape with leafless trees, a grey sky and fields bare of crops. The farmstead sits in the centre and, from Lampitt’s depiction, we can trace the farm’s origins and several phases in its development. This is, almost certainly, a product of the process of parliamentary enclosure, perhaps somewhere in the Kentish Weald in the 18th century. (Enclosure was the process by which common land and strip farming in open fields was brought into private ownership and the landless – who relied on access to commons to graze animals – were forced from the land.)

How can we tell? The boundaries in this landscape are straight. A surveyor’s pen drew them and his chains and lines made them a physical reality. The hedges are mostly of single species – hawthorn waiting for its May blossom – interspersed with trees. These are elms.

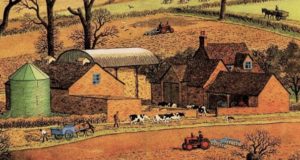

The farmstead is small, placed conveniently in the middle of a new farm of rectilinear fields. It is neat and we can see its square, brick-built, barn clearly fronting onto a yard. The house is separate and has a private garden looking onto an orchard. It’s all about 150 years old and this is a ‘mixed’ farm where crops (arable) are grown alongside a variety of livestock. This is now, writing in the early 21st century, a lost world. Yet we can see evidence of the medieval and later landscape of open fields, shared by the tenants of the manor: there’s a hump in the field to the left of the farm. This is surely the headland, where ploughs once turned between two fields, now ploughed out.

Lampitt has captured a time of change. The Labour government’s 1947 Agriculture Act secured prices and hastened investment and development and here we can see the tangible results in affordable technology. This farm is perhaps the result they imagined. That is most obvious in the juxtaposition of bright red tractors – the nearer pulling a disc harrow, breaking up the heavy Kentish clay, the further ploughing – and the horse pulling carts. The Second World War brought American tractors to the British countryside in huge numbers (the same ‘Lend Lease’ programme supplied tanks and planes in their thousands). The lasting effect of the names John Deere, Minneapolis Moline and Allis Chalmers and their machines was more dramatic.

But there are other machines. Some are visible in the cartshed by the barn, perhaps built for horsepower and modified for the tractor, before being replaced and dumped in the hedgerows.

Even where the machines themselves are invisible their presence is felt: the sheep are hemmed in by square bales of straw, providing some shelter from the winter winds.

Other changes have taken place. The corrugated metal tower with the pointy roof is a grain silo, storing the crop in bulk rather than in sacks. The curved roof ‘Dutch’ barn supplements the thatched hayrick. It’s unlikely that any of these buildings would have been there before the war.

Yet there are more changes still to come. This landscape has not yet seen the combine harvester: the hedges are maintained and not yet ripped out. We can see some newly pleached with trimmings being burned. The gates have not yet been widened. The elms will be lost to Dutch Elm Disease in less than a decade introduced, like many of the first tractors, from North America.

Even the animals signify the time. The black and white cows that most urban dwellers think of as normal (on milk bottles and childrens’ books) are Holstein Freisians, another post-war introduction. These were the tools by which farmers boosted milk production, but they displaced native breeds like the Dairy Shorthorn and native, dual purpose (milk and meat) breeds.

This contrast and their coexistence can be seen in this wonderful film of the Melplash Show (Dorset) in 1957:

Towards the end of the film there’s a parade of cattle for judging and the Holstein Freisians are outnumbered. The drive for greater milk yields meant that soon they would be ubiquitous and this would change how farms such as this would work and look. Mixed farms became specialised and, ultimately, larger and less diverse.

But for now this mixed farm has modernised but not changed completely. While horses no longer speed the plough they are still present, an integral part of farming life. This means that the farmer would have grown oats for their feed and maintained stables.

The two horses in Lampitt’s picture are at work hauling what look to be ‘tip carts’. While the horses’ days are numbered, the carts themselves might linger on. The picture below shows one such cart, its shafts sawn through and replaced with a tow bar. The power of the tractor means that the sides have been extended by ‘greedy boards’ to increase the load it could take and pneumatic tyres on wheels from a scrapped car added.

Not all on the modern farm was new.

Ronald Lampitt saw all this and recorded it for Treasure Magazine. It can be dated, just by what it shows, to a February day in the late 50s [the picture was published in 1963 but may have been produced a few years earlier] but the details it includes show the past and present of this small farm and hints at its future.

This blog was originally produced for Helen Day’s Ladybird Fly Away Home. Follow her on Twitter: @LBflyawayhome. Thank you to Helen for allowing us to reproduce it here. Adam Chapman is a Lecturer in Medieval History at the Institute of Historical Research and the Principal Editor of the Victoria County History. Follow him on Twitter @DrAdamChapman.