By Henry Irving

This guest post comes from Henry Irving, a member of the advisory board for the IHR’s Centre for the History of People, Place and Community. Here Henry outlines his current research on the home front in Leeds and his forthcoming 3D tour of one of the city’s wartime shelters: ‘Inside the Hidden Shelters’ takes place at 2pm on Saturday 19 September and you can book here.

It seems it is impossible to escape the Second World War during a time of crisis. The conflict has been woven throughout British commentary on COVID-19 – from ‘Blitz spirit’ before lockdown to ‘D-Day’ as offices and schools began to re-open. So blurred have the lines become that a Spitfire bearing the message ‘Thank U NHS’ has just undertaken a national tour, flying over hospitals in aid of the NHS Charities Together.

Coinciding with the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Britain and the 75th anniversary of VE and VJ Days, such examples have sat alongside more specific commemorations. In effect, the public history of the war is operating on two levels: one emphasising national togetherness and resolve, and another focused on the sacrifices made by particular communities. This duality of local and national reflects the way that the war effort was presented on the home front from 1939.

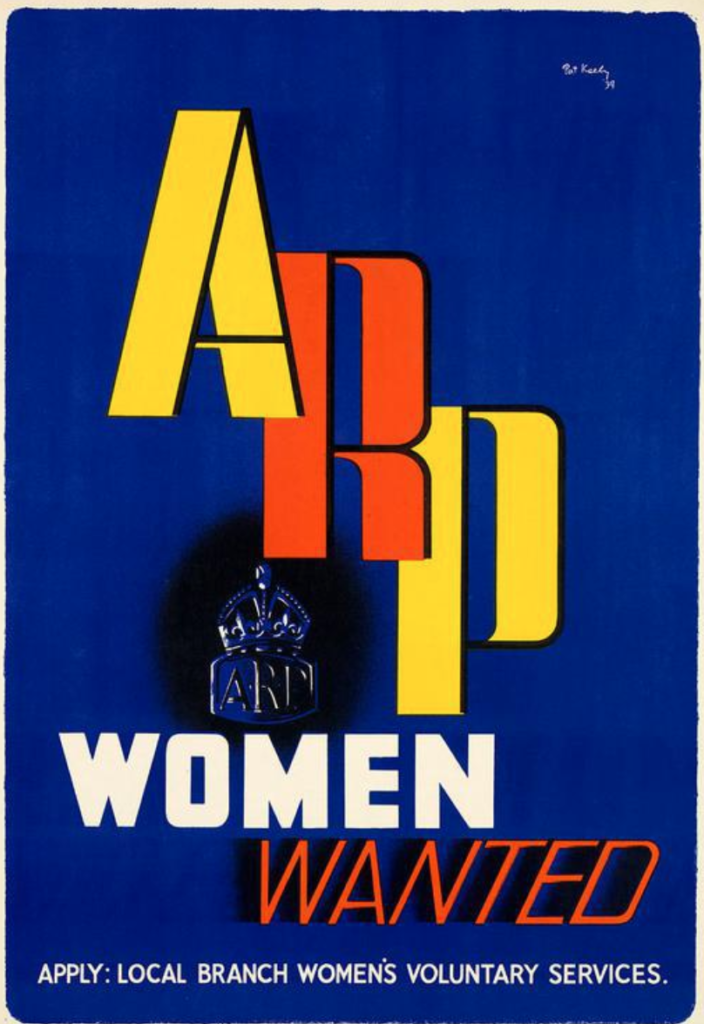

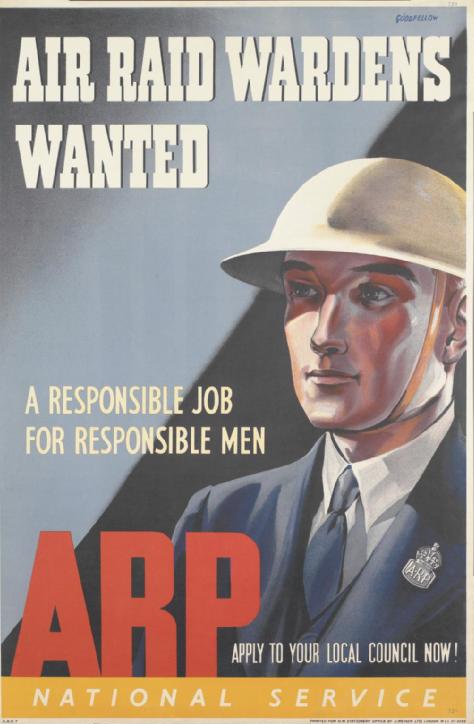

Take the example of Air Raid Precautions, which was later re-badged Civil Defence. I recently completed a chapter on Civil Defence recruitment with Jessica Hammett – whose work on wartime community provides a new perspective on the idea of a ‘people’s war’. We were particularly interested in the relationship between national and local recruitment campaigns, as it was ultimately up to local authorities to provide Civil Defence for those they represented.

We found that volunteers were motivated by a mixture of factors that cannot easily be disentangled. Government campaigns encouraging ‘National Service’ and localised advertising helped to raise awareness, but many volunteers appear to have required an extra push. This could take the form of an external event, the increased visibility of Civil Defence measures in a particular place, or personal persuasion within the community. The importance of informal recruitment was well understood by those responsible, who used training activities, demonstrations and social events to encourage participation. If you’re interested, the chapter will be published in November.

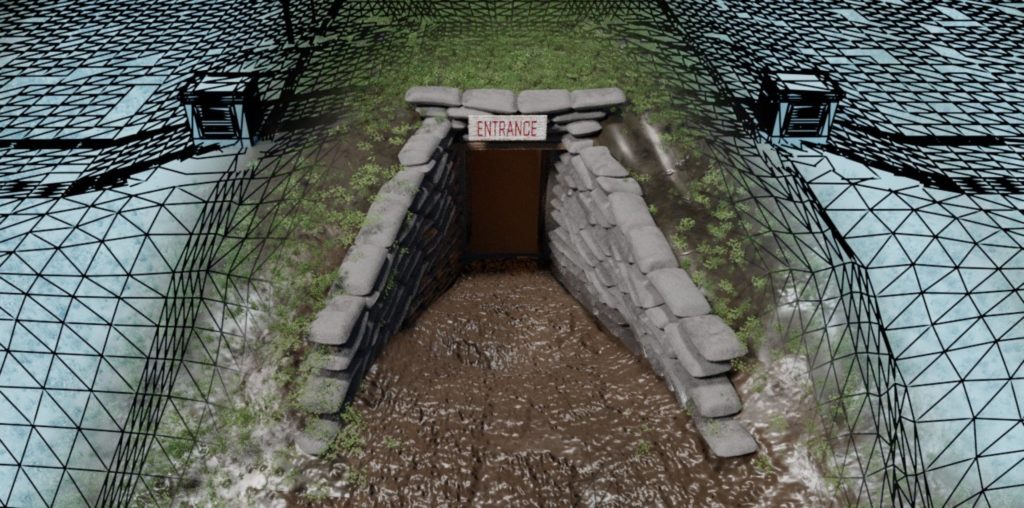

My dabbling in the history of Civil Defence has led me to some unexpected places. Personally, the most exciting is a collaboration with a freelance heritage artist, Jorge de Pedro, who asked me for advice about a 3D computer visualisation of a Leeds air raid shelter. I knew the example well: sited in Woodhouse Moor, at the heart of the city’s university district, I would walk past the shelter on my pre-COVID commute and used it as an example when lecturing on the Second World War.

The structure is one of 31 trench shelters built by the City of Leeds as part of a national building programme in 1939-40. Bricked up and grassed over at the end of the war, they are mostly forgotten relics of their time. Their continued existence is particularly anomalous in Leeds, as the city escaped the worst of the Blitz, being subjected to only nine raids during the war.

But what was true of Civil Defence recruitment, was also true of air raid shelters. Structures like the one on Woodhouse Moor expose the relationship between national and local war efforts.

The research we completed to prepare the model suggested that Leeds was one of the most active local authorities when it came to Civil Defence preparations. The city published a wide-ranging ARP plan in 1938, was home to Britain’s first municipal training centre for anti-gas measures and organised the second largest peacetime training exercise in Britain (which was attended by 60,000 people and also took place on Woodhouse Moor).

Yet the city entered the war without enough shelter space, as government policy promoting domestic shelters was poorly suited to local housing stock. The famous Anderson shelter was completely unsuited to a city whose urban centre was dominated by approximately 70,000 back-to-back terraced houses.

Trench shelters like the one on Woodhouse Moor were the result of a panicked effort to provide shelter space once war was declared. Built too late to placate criticism in a city that avoided the worst of the bombing, the shelter was quickly superseded by new forms of domestic and communal protection. Viewed in this way, it is a relic of the importance of people, community and place within the Second World War.

While a 3D model cannot recreate this history in its entirety, we hope that it will provoke discussion of the local and national histories of the Second World War. The results will soon become clear, as we’re (virtually) inviting people inside the shelter as part of the Heritage Open Day programme. Our event, ‘Inside the Hidden Shelters’, combine, an overview of Leeds Second World War history with a tour of a new 3D model showing how the shelter would have looked in 1940-41.It takes place at 2pm on Saturday 19 September and you can book your place here.

Henry Irving is Senior Lecturer in Public History at Leeds Beckett University and a member of the Advisory Board for the IHR’s Centre for the History of People, Place and Community.