By Sam Manning

Cinemas are just one of the popular public arenas required to close during the current COVID-19 emergency. But for many UK venues this crisis has historical resonance.

Here, cinema historian Dr Sam Manning considers how the film industry and British regional cinemas responded to earlier public health crises, including influenza outbreaks, during the twentieth century.

Sam’s research forms part of his new book, Cinemas and Cinema-Going in the United Kingdom. Decades of Decline, 1945-65, published in March 2020 by the University of London Press. His monograph appears in the ‘New Historical Perspectives’ series from the IHR and Royal Historical Society and is available free as an Open Access title.

During Oscars season back in February, I argued that cinema’s doom-mongers should look to the past to consider how theatres have dealt with threats, such as the emergence of television. Little did I know then that cinemas would be forced to temporarily shut their doors in response to a global pandemic.

This led me to consider what my research can tell us about how cinemas have historically responded in times of crisis. A case study of twentieth-century Belfast highlights the resilience of cinemas, whose proprietors have successfully negotiated pandemics and civil conflict to provide entertainment for their patrons — at a time when they perhaps needed it most.

I first became interested in Belfast’s cinema history when I started researching interwar cinema-going seven years ago. I focused on the operation of the Midland Picture House, a cinema with a working-class customer base located near the docks of north Belfast. This venue overcame a range of crises, including economic recession, sectarian conflict and the logistics of switching from silent to sound cinema. The Midland also survived several public health scares at a time when cinemas were highlighted as unsanitary venues in the press and by local government.

In February 1929, the Belfast News-Letter reported that a ‘severe epidemic of influenza, with its attendant widespread distress… has affected Belfast for several weeks past’. In response, the Northern Ireland Public Health Department wrote to all cinemas outlining the dangers of the spread of influenza.

Though cinemas were allowed to remain open, the Belfast Corporation requested that venues should be ‘thoroughly ventilated and sprayed with disinfectant at regular intervals. The entertainment should not be carried on for more than 2½ hours and there should be an interval of not less than 15 minutes between two entertainments’.

The Midland was one of four Belfast cinemas destroyed during the Blitz in 1941. Most other cinemas fared much better and admissions rose sharply as audiences sought escapism and entertainment during the Second World War. My new book, Cinemas and Cinema-Going in the United Kingdom: Decades of Decline, 1945–65, uses case studies of Belfast and Sheffield to explore how cinema audiences changed after the war and assesses the response of exhibitors to the post-war slump in attendance.

Though my book was completed before the present crisis, it provides several examples of how cinemas responded to public health concerns. For instance, in October 1957 the Belfast Telegraph reported that a recent influenza epidemic had cut audiences in Belfast by between one third and a half. Though cinemas again remained open, the article claimed that the recent growth of television meant that people preferred to stay at home where there was no chance of infection. Further reports suggested that audiences only returned to their normal attendance levels at the beginning of the following year.

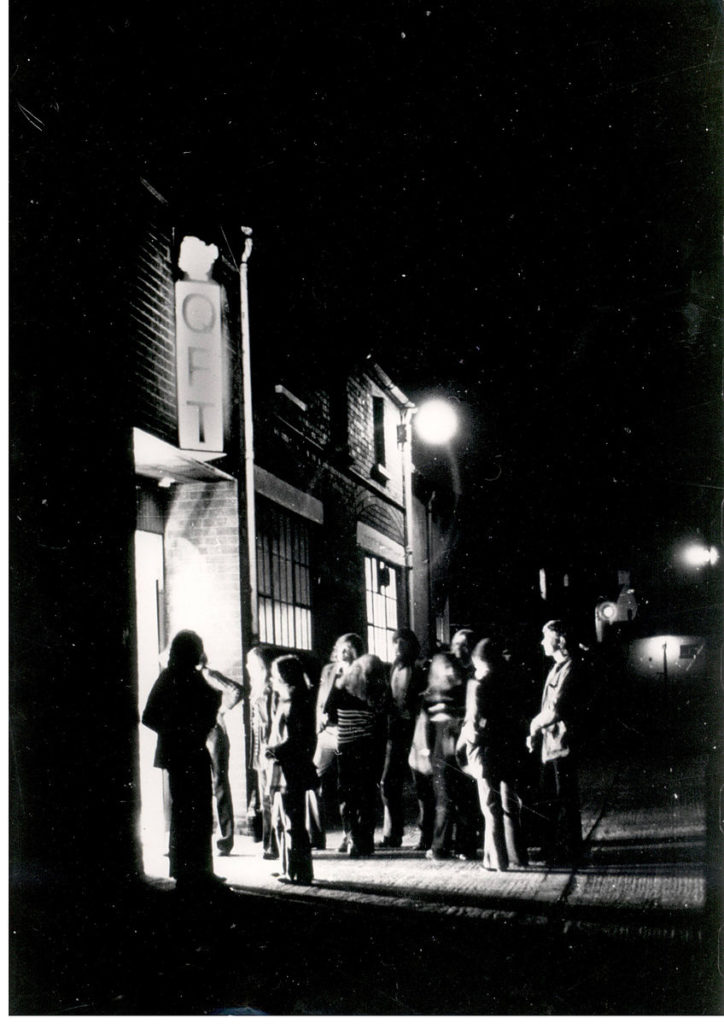

In 2018, I researched the fifty-year history of Queen’s Film Theatre. It was clear that the difficulties of establishing and developing a cultural cinema were heightened by the onset of the Troubles from 1969 onwards. This period of unrest often impacted cinema programming and operations. In 1970, for instance, Queen’s committee reported that a recent run of poor attendance was ‘largely due to the civic conflict in Belfast’.

However, Queen’s Film Theatre fared better than many other venues. In September 1977, a series of IRA firebomb attacks damaged three Belfast cinemas: the ABC, the New Vic and the Curzon. All these venues displayed resilience and reopened shortly afterwards. The Curzon resumed business in December with a showing of Star Wars. John Gaston, the cinema owner, told the local press that the popularity of the film reminded him ‘of the good old days of the cinema before television’. The Curzon then remained open until 1999 and was the subject of a recent documentary.

In my previous blog, I argued that thinking historically warns against overstatement in light of recent declines in cinema attendance. While the current closure of cinemas is largely unprecedented, I believe that looking back to previous crises offers hope for the future. Audiences and exhibitors have consistently found ways keep to cinemas going in times of crisis, and I have no doubt that they can weather the current storm.

Dr Sam Manning teaches at Queen’s University Belfast and is a postdoctoral researcher on the AHRC European Cinema Audiences project at Oxford Brookes University. He has recently published articles on the history of cinemas in Northern Ireland in Cultural and Social History and Media History.

Cinemas and Cinema-Going in the United Kingdom. Decades of Decline, 1945-65, is now available as a free Open Access text from the University of London Press.

‘New Historical Perspectives’ is a new series from the Institute of Historical Research and the Royal Historical Society. It publishes monographs and collections by Early Career Historians, with all titles available Open Access and as print and eBook editions.

Watch Sam discuss his research and new book on a recent episode of History Now from Northern Visions TV.