By Sara Charles

The medieval scriptorium conjures up images of light and shadow, with rows of hunched figures stooped over ruled parchment, quill in hand, under the watchful eye of the master. This is largely the scene that’s portrayed in the recent TV series The Name of the Rose, commissioned by the Italian channel Rai 1 and now shown on the BBC, based on Umberto Eco’s novel from the 1980s.

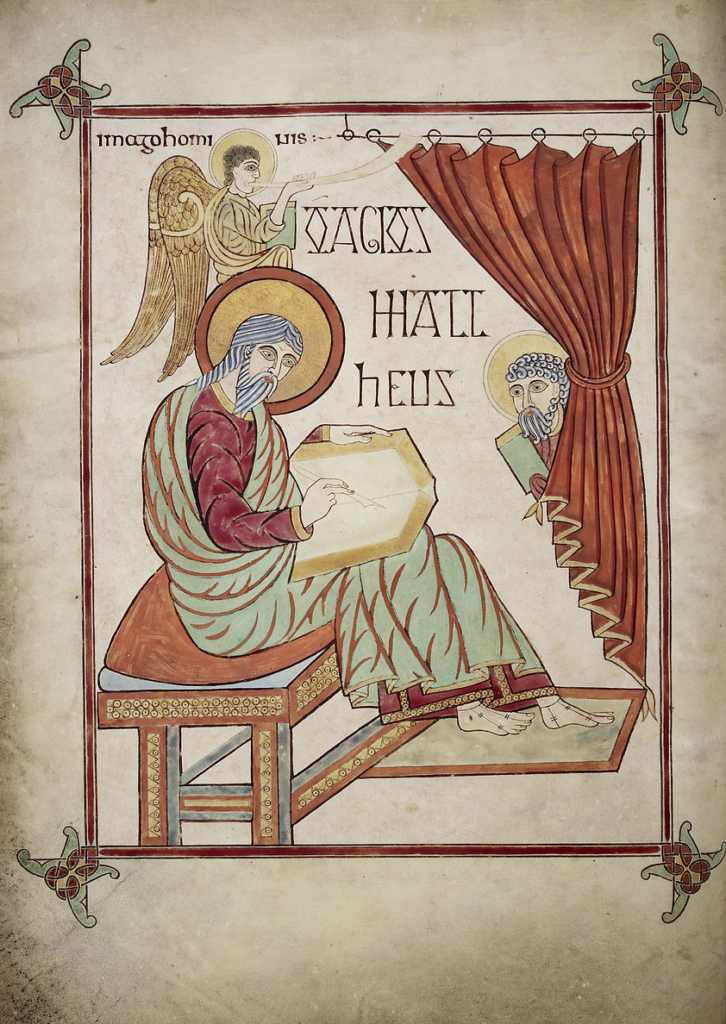

But how accurate is this depiction? Although we can all picture a scriptorium in our heads, there is actually very little surviving evidence for them, architecturally or from manuscripts. There are some commonly used manuscript images showing monastic scriptoria, but as Eric Kwakkel has pointed out, they do not seem to be accurate representations. Most images of scribes are pictured individually, not part of a communal enterprise, as you can see from the image above.

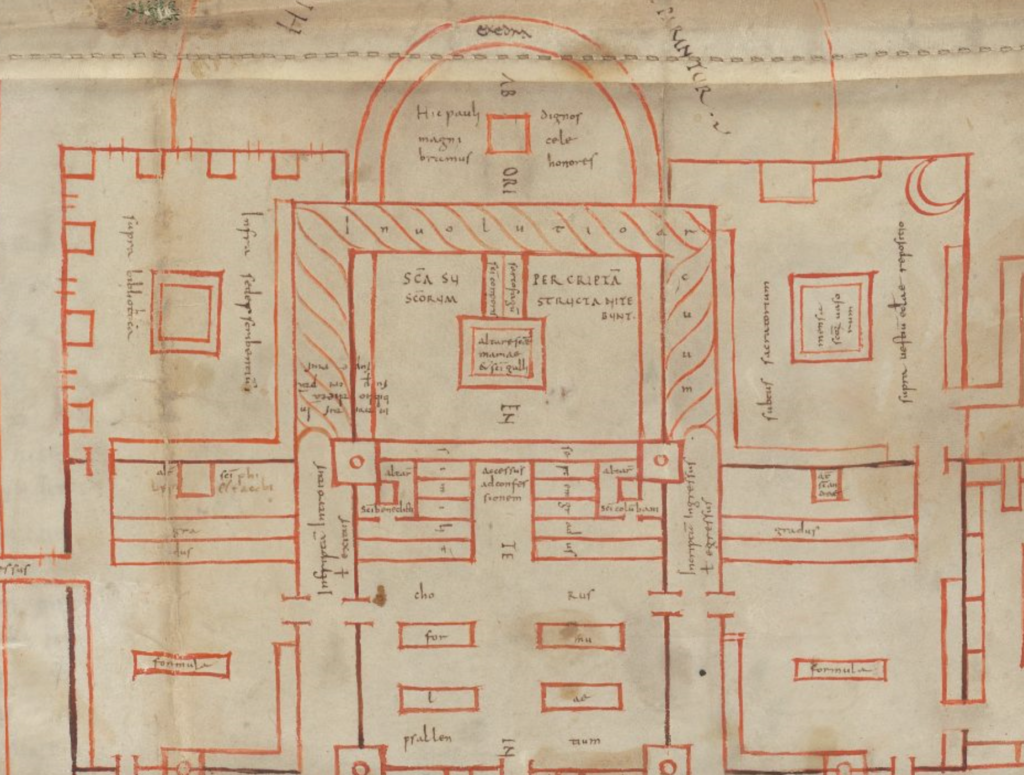

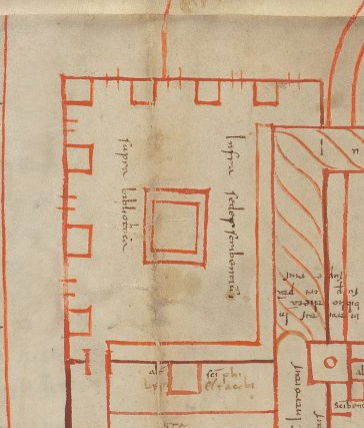

Some rare architectural plans from the monastery of St Gall (c. 820-830) show a scriptorium situated below the library at the east end of the abbey (top left on the plans). Labelled Infra sedes scribentium, supra bibliotheca (below, the writing seats, above, the library), we can see a large desk in the centre, with seven desks on either side of the windows. With the corner location, and the desks pushed to the walls, this would have maximised the natural light coming in, and probably gave Umberto Eco the inspiration for his scriptorium and library.

Yet most medieval monasteries would not have had a such a room. It is thought that the Lindisfarne Gospels, a sumptuously decorated and beautifully scripted manuscript, was produced by one monk, Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne (698-721). Much of the manuscript was probably produced when Eadfrith was on retreat on a small island called Cuddy’s Isle or St. Cuthbert’s Isle. This would hardly have been a luxurious scriptorium with materials already prepared – no table or angled desk, and probably using shells to hold paint.

Image credit: Hornbeam Arts, Flickr

Although monasteries immediately spring to mind when picturing manuscript production, there was actually a lot of lay input too. As Richard Sharpe explains in the 2019 Lyell lectures, there was much more interaction and trade between the monasteries and the outside world than we tend to think. Also, once the universities were founded in the late twelfth century, much manuscript production moved from the monasteries to new sites of learning. These would have had areas, such as Catte Street in Oxford, devoted to the various stages of book making, with residents including Roger Parmentier, Thomas Scriptor and Peter the Illuminator.

So, in light of this, how do TV adaptations cope with a lacuna of knowledge, and how much is recreated with a visual impact in mind, regardless of truth? On the whole, most of the reconstruction of a scriptorium for The Name of the Rose was accurate. The original description in Umberto Eco’s novel goes into some detail in its account of the inkhorns, quills and rulers being used, and the sloped desks with a lectern to copy manuscripts; but seeing it on screen really brings the day-to-day working environment to life.

Although the tables are shown in more of a haphazard arrangement than the plan from St. Gall, and distinctly lacking in natural light, the overall sense is of a busy and orderly environment. There are parchment skins being stretched on frames, folios hung up on lines to dry the ink and rolls of parchment housed in different compartments (presumably by size, quality or type).

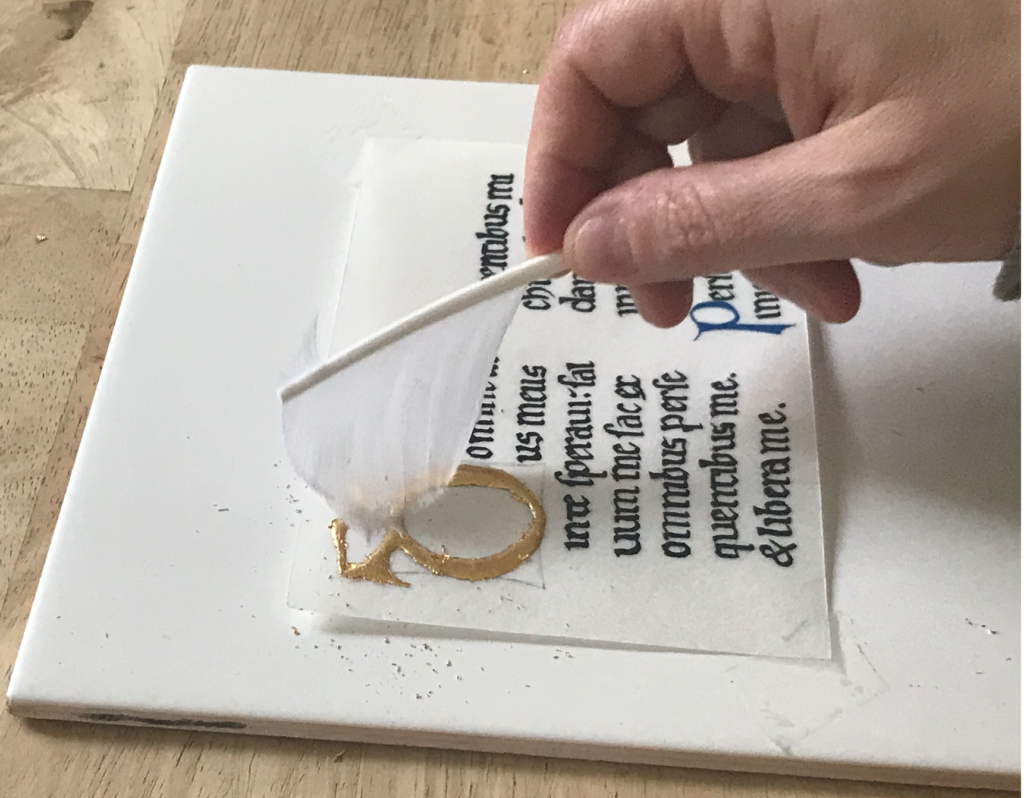

A maddening feature of most media depictions of quills is to display them with a great plumage, which would have been completely impractical to write with. In reality, quills would have been mostly defeathered, with a small tuft left at the end. This is brilliantly displayed in a scene in the first episode where we see an illuminator softly brushing away the excess gold leaf he has just applied.

However, this modern-day representation raises other issues of historical accuracy. Loose gold leaf is wafer-thin, and requires absolute stillness to work with — as the twelfth-century author Theophilus explains in his treatise on the arts, De diversis artibus. In book one, chapter 29, he advises when applying gold leaf: ‘et hora oportet te a vento cavere, et ab halitu continere, quia si flaveris, petulam perdes et difficile reperies’ (and then you must beware of the wind, and hold in your breath, because if you breathe you will lose the leaf and have difficulty recovering it). So, I find it surprising that an illuminator would be working in the middle of a busy scriptorium, at the mercy of drafts and breezes from all around him.

A second issue is that the recent TV depiction shows the illuminator working at an angled desk. Now, it is true that scribes worked at slanted tables, to ensure the correct flow of ink. If you try writing with a quill on a flat surface, the ink does not flow from the quill very easily. But when illuminating, before applying gold leaf you need an adhesive, such as plain egg-glair or gesso (a plaster-of-Paris liquid mixture) that is painted onto the surface. This would definitely need to be horizontal, to ensure even application.

Gesso also takes about twelve hours to fully dry, so it would need to be flat for the whole of this period. The gold is then applied by activating the gesso by breathing on it, and applying pressure firmly to the gold over the gesso. None of this would be easy to do on an angled surface. In the TV recreation, it also appears that the illuminator is applying gold to an initial that has already been painted, which is not the correct sequence of events. Rather, the text was first written by a scribe, then gold leaf was applied, with the painting coming last.

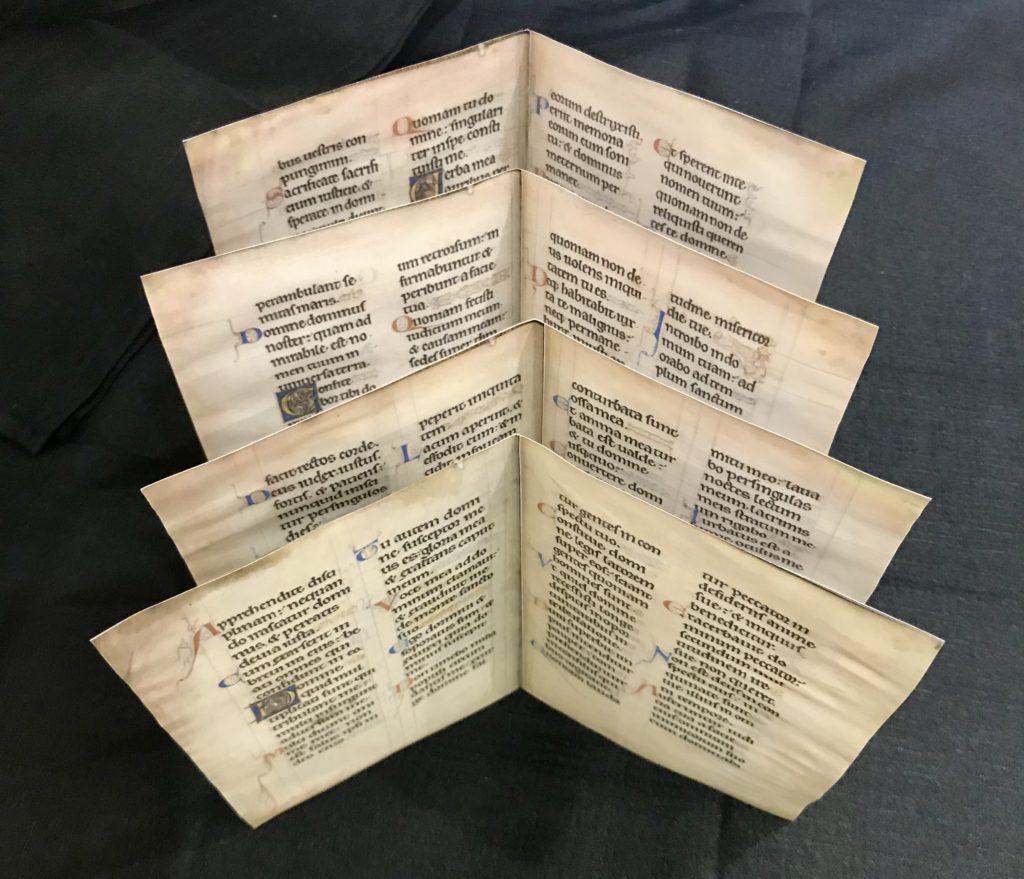

The other thing that seems odd about the on-screen scriptorium is the frequent depiction of single folios, used on only one side. No matter how wealthy the monastery, parchment was an expensive material. In order to form a standard quire, four large sheets of parchment were taken and folded in half, to form a quire of eight folios (or sixteen pages). Occasionally, if something vital had been forgotten, or you needed one extra folio to finish a passage, a single folio would be tipped in, but bifolios were very much the norm. In the light of this, to be repeatedly shown just single-sided folios seems odd.

Image: Sara Charles

On-screen it’s lovely to see the manuscripts being used by the monks in their everyday business, away from the library. For example, Severinus, the abbey’s herbalist and scientist has a herbology in his room on a stand, clearly placed there for ease of consultation. It’s also interesting to see the use of paper in the scriptorium, as paper mills were appearing in Europe by the late fourteenth century. To see Salvatore’s paper mill in action was a delight, although I confess that I do not know enough about paper manufacture to know if this was accurate!

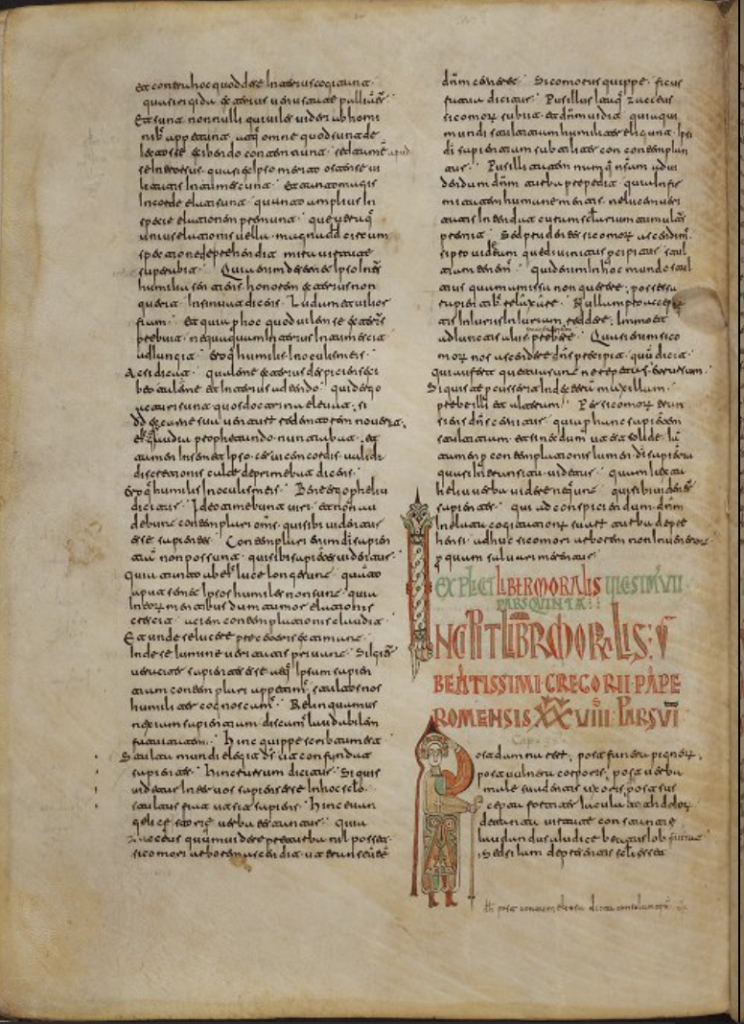

But the most fun thing about watching the TV adaption of The Name of the Rose has been spotting folios from well-known manuscripts. In the first episode, an image of Matthew from the Lindisfarne Gospels is clearly seen on one of the desks in the scriptorium, and appears in several other background shots. In the library scene when Aldo is overcome by the fumes and begins to hallucinate, the folio he is looking at is from a visigothic manuscript on St Gregory’s commentary on Job (John Rylands Library, Latin MS 83, fol. 336v/no.555). On closer inspection, however, this manuscript does not correspond to the original, as on-screen the opposing folio is a depiction of the seven-headed beast from Revelations.

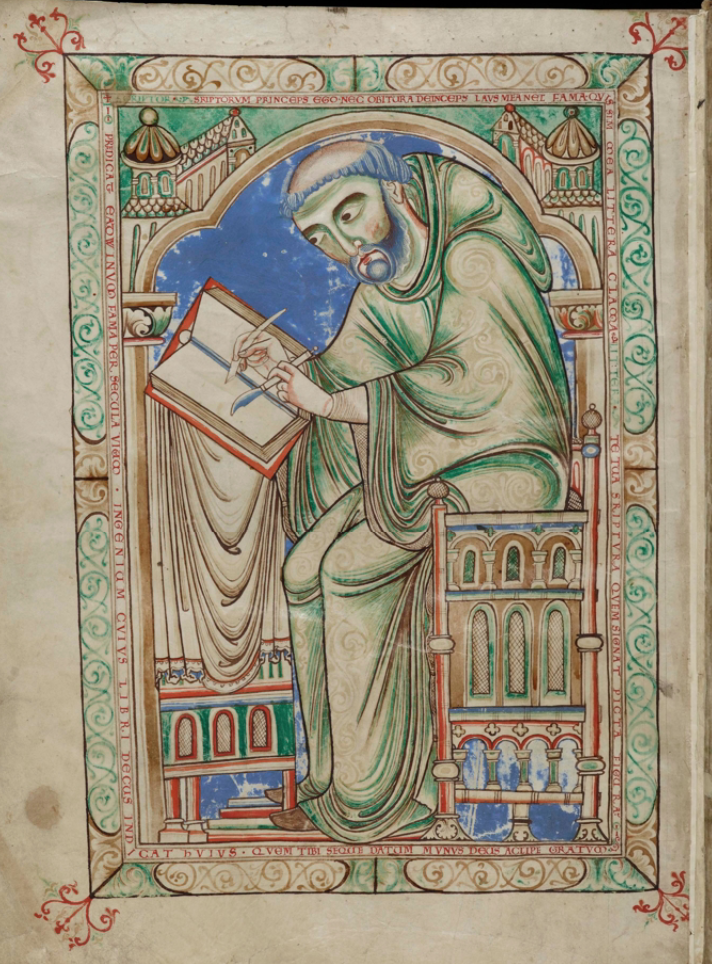

In the scene where Nicholas presents William of Baskerville with a new eyeglass in his outside workshop, William leafs through a nearby manuscript, where we can spot a well-known medieval figure — Eadwine the scribe from the Eadwine psalter. This portrait is from a manuscript produced at Christ Church, Canterbury c. 1160, and in his portrait Eadwine is described as s[c]riptorum princeps (chief of scribes). This folio comes at the back of the Eadwine psalter, yet in the BBC depiction it features mid-way through a manuscript, with the text from the book of Exodus on the following page (although to be fair, the script and the coloured initials on this folio are very much in the twelfth-century style). William of Baskerville reads the text as Theophilus’ Treatise on the arts — which it is clearly not — yet it does at least make sense to have that text in a craftsman’s workshop, and is a nice touch. This exchange with the manuscript does not feature at all in Eco’s original text.

It is interesting that the series producers chose to represent these manuscripts in this way. They have copied folios from different manuscripts and bound them together, yet kept the same style: therefore, the visigothic folio from John Rylands Library is shown with the Revelations image, which also is very Spanish in style, and the Eadwine portrait is paired with folios that similarly compliment the style.

In doing so, the TV producers have gone for visual impact. This may mean that the correct manuscript is not being discussed; but it does show the variety of different scripts and texts that would have been on hand in a well-stocked monastery, and the book networks that linked the Christian and Muslim world. In episode four, when William and Adso are once again exploring the library, William finds a copy of Ibn al-Haytham’s Treatise on Optics, shown in its original Arabic, which reminds us that knowledge was shared in many different languages in the medieval period. The folios are often exact copies of well-known manuscripts, and a lot of care has been taken to depict them as genuine medieval books (although fellow book historians may wince at the open flames and the haphazard way books have been stored in the library!).

I doubt many other viewers of The Name of the Rose will have watched the series for minor discrepancies in manuscript production. But as a book historian, I find it fascinating to see the things I study come to life in this way. And as there are quite a few gaps in our knowledge, it often comes down to personal interpretation. Many of the quibbles I have with the on-screen scriptorium come from my own experience of working with these materials, and of using them in the way that I find easiest — but that’s not to say this is right, or the only way. What’s interesting is the way books are represented on-screen in a myriad of different ways, yet always perform a vital function. For more on this, see the excellent work done by Dot Porter and Brandon Hawk on manuscripts in Star Wars and the Dark Crystal.

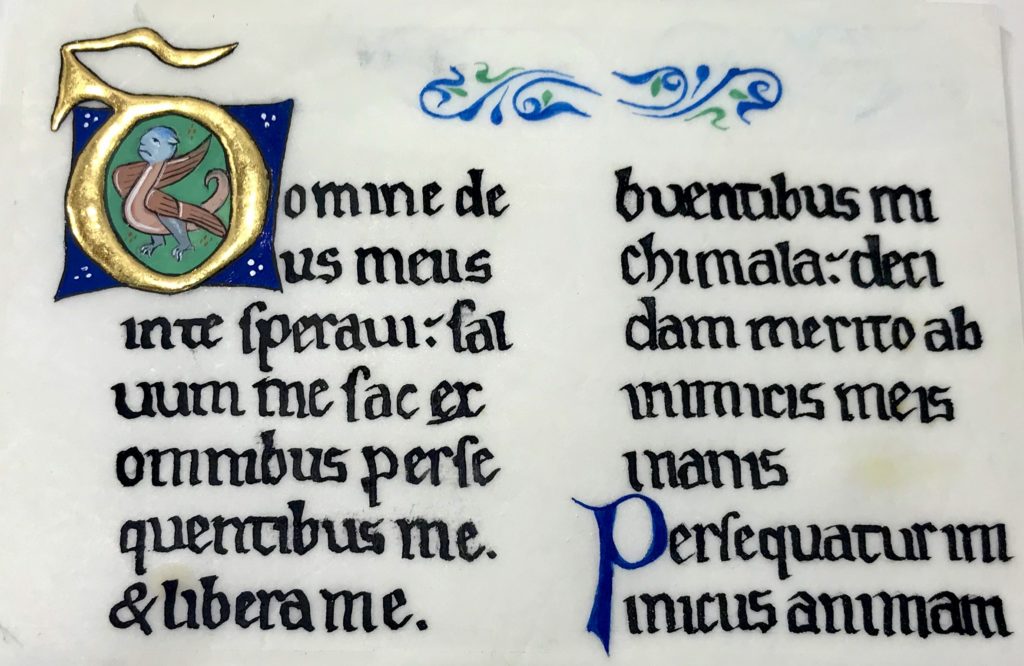

A modern-day scriptorium

Copy of 13th century psalter

Sara Charles is a medieval historian, specialising in book history, hagiography and women’s lives. She is currently studying for a PhD on medieval martyrologies at the Institute of English Studies, University of London. Sara is also assistant editor for the IHR’s academic journal, Historical Research, and for the Bibliography of British and Irish History published by the Institute of Historical Research and the Royal Historical Society.