by William White

In recent years, concerns about the use of disinformation in politics have become increasingly widespread on both sides of the Atlantic. ‘Post-truth’ was the Oxford Dictionaries’ ‘Word of the Year’ for 2016, in the immediate aftermath of the vituperative Brexit referendum and a US Presidential Election that featured allegations of cyber-based conspiracy and subterfuge. The threat posed by ‘fake news’ is now a recurring refrain in newspaper columns and on social media, with the term becoming something of a personal catchphrase for the current occupant of the White House.

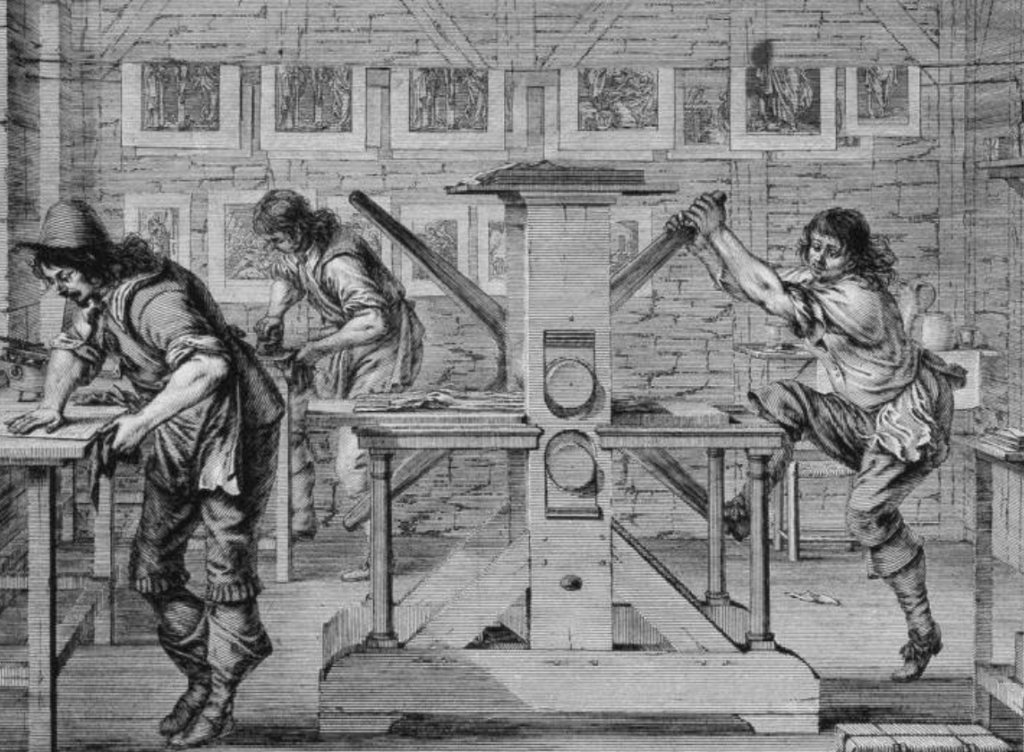

It seems a good time, then, for historians to refocus attention on the England of the early 1640s, where parallels with recent events abound. As tensions between Charles I and his parliament steadily escalated, the nation was gripped by constitutional crisis, ideological polarization, and a conspiratorial paranoia. The king, MPs, and the public all struggled to come to terms with a political culture in which relatively recent technology – in the form of the printing press – had begun to play an unprecedented role.

Moreover, partisan pamphleteers and newsbook writers, whether royalist or parliamentarian, were quick to accuse each other of fraud and wilful deceit – of, in essence, peddling ‘fake news’. The English public, previously unused to these levels of open political disagreement, were now forced to choose between a bewildering array of mutually incompatible claims about what was happening and who could be trusted. As a result, historians have sometimes spoken about a ‘crisis of truth-telling’ in this period.

Much less attention has been paid to disinformation as a deliberate tactic employed for political or polemical advantage during the revolutionary decades. But, as I show in my article, neither parliamentarians nor royalists were above employing covert, underhand, and entirely dishonest methods in their attempts to manipulate public opinion and gain popular support. I focus particularly on the months surrounding the outbreak of the first English civil war (1642–6) and on the publishing activities of the parliamentarian war party.

Examples of newsbooks

From the moment the fighting started, there were loud calls from the public and from politicians on both sides for an accommodation that would avert further bloodshed. This resulted in a series of abortive peace negotiations during early 1643, known as the Treaty of Oxford. Not all parliamentarians, however, were convinced of the wisdom of seeking an early resolution to the conflict. A pro-war faction emerged at Westminster, centred on John Pym and backed by radical groups outside parliament, which aimed to undermine peace talks and secure funding for further militarization. This war party was desperate to show the untrustworthiness of Charles I and those closest to him – why they might renege on any peace treaty as soon as it was signed and why absolute victory was therefore essential.

It is in this context that we see the emergence of a great many fake and forged publications during the winter of 1642–3. Declarations, speeches, letters, and sermons began to be printed with completely spurious claims made on their title-pages regarding their provenance: who had composed them, where they had been published, and why. These were often attributed to the king or his councillors, apparently by war-party activists in the hope of demonstrating to fellow parliamentarians, tacitly and subtly, the folly of a swift peace settlement.

To take just one example, January 1643, the month before the start of the Treaty of Oxford, saw the publication of The Earl of Dorset his speech for propositions of peace: delivered to His Majesty at Oxford. The title-page tells us only that this text was printed in London – by or for whom remains unclear. In the speech itself, the earl offers the king a Machiavellian strategy for regaining his throne and powers. He should ‘seem to yeeld to the demands’ of parliament at first, but could then ‘remove the objects by degrees, turne the humours some other way for a more seasonable opportunity’. In essence, Charles was being advised to negotiate in bad faith and to go back on any promises he made to parliament that might limit his power.

This would seem, on the face of it, to provide perfect evidence that royal policy was characterized by duplicity and insincerity, and that MPs could not trust the king’s word in the coming peace talks. The arguments put forward by Dorset ‘exposed’ an alarming discrepancy between the king’s public presentation and the conspiratorial reality that underpinned his political decision making.

However, this speech was never actually delivered at Oxford, either by Dorset or by any other privy councillor. It had instead been lifted almost verbatim from a manuscript that pre-dates the civil wars altogether. In this manuscript, which circulated widely in the late 1630s, the speech was attributed to James Stuart, duke of Lennox, and presented as commentary on the recent Covenanter uprising in Scotland. In the version published the following decade, the words supposedly delivered by Lennox were relocated to Oxford in January 1643 and put into the mouth of a more probable speaker.

Why, exactly, did the parliamentarian war party resort to this subtle strategy of disinformation? For one thing, these kinds of forged publications allowed them to generate fears about the untrustworthiness of Charles I without being seen to attack the peace process directly. But, perhaps more importantly, these texts also conveyed the impression of royal conspiracy more forcefully and persuasively than conventional polemic could: they provided evidence rather than simply allegation.

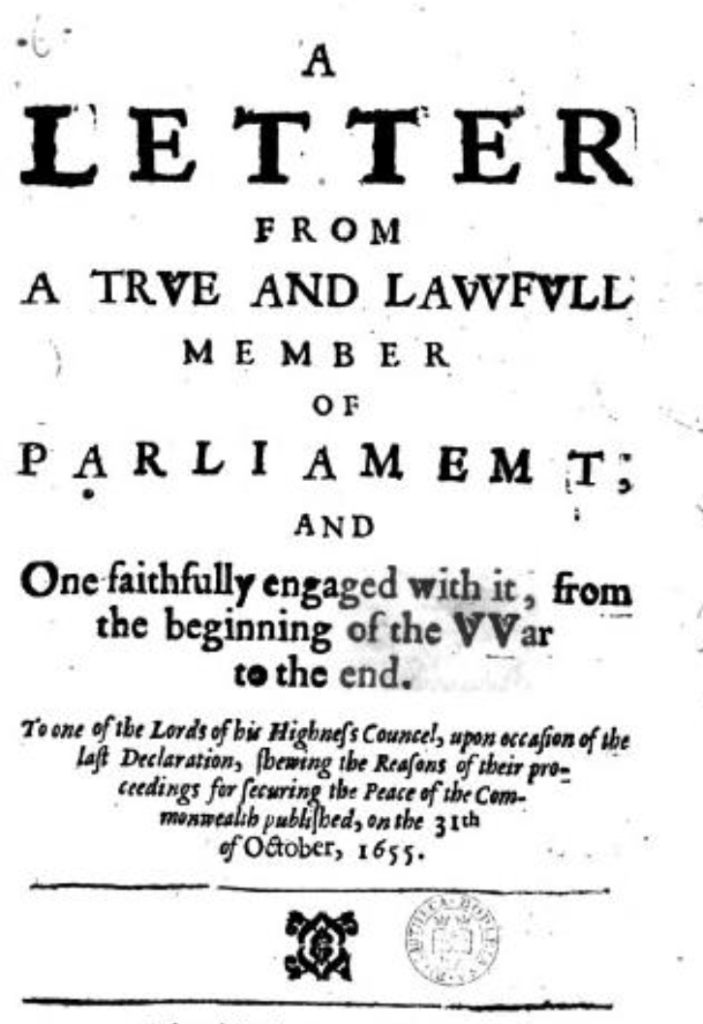

Indeed, the utility of disinformation was soon recognised by other groups. In 1643, for example, the royalist William Chillingworth penned a fraudulent petition purporting to represent ‘the most substantial inhabitants of the City of London’, which put into the mouths of London citizens a fierce denunciation of parliament’s conduct. Perhaps the most impressive example of forgery during the entire period of civil war and the Interregnum, however, was provided by Edward Hyde, later earl of Clarendon, in 1656. His Letter from a True and Lawful Member of Parliament was an attack on the Cromwellian regime supposedly written by an erstwhile parliamentarian MP, widely believed by contemporaries to be the work of Sir Henry Vane the younger. Only in the nineteenth century, when a manuscript in Hyde’s hand was discovered, was his authorship of the letter established.

I think this all matters for two reasons. First, it is a timely reminder that the use of disinformation and deceit as means of controlling public opinion is by no means a recent development in the history of political communication. Secondly, it offers a warning to historians of the civil war specifically. When studying the great mass of pamphlets that poured from the nation’s presses in these years, we cannot always be overly trusting of the claims made on title-pages regarding authorship, publication, or context. We might, after all, be dealing with more ‘fake news’.

William White is a D.Phil. student at the University of Oxford. His research examines royalist and episcopalian preaching during the English Civil Wars and Interregnum.

The November issue of Historical Research, featuring William’s article, is now available.