By Catherine Delano-Smith

Dr Catherine Delano-Smith, Senior Research Fellow at the IHR, is leading a new project with Nick Millea, map curator at Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, entitled ‘Understanding the medieval Gough Map through physics, chemistry and history’.

The project, recently funded by the Leverhulme Trust, is an ambitious multi-disciplinary programme which brings together a team of 30 researchers comprising medieval historians and specialists in the physical sciences and digital imaging. Together they will study the map’s regional content, provide the first dedicated study of its place-names, and examine the map’s codicological aspects.

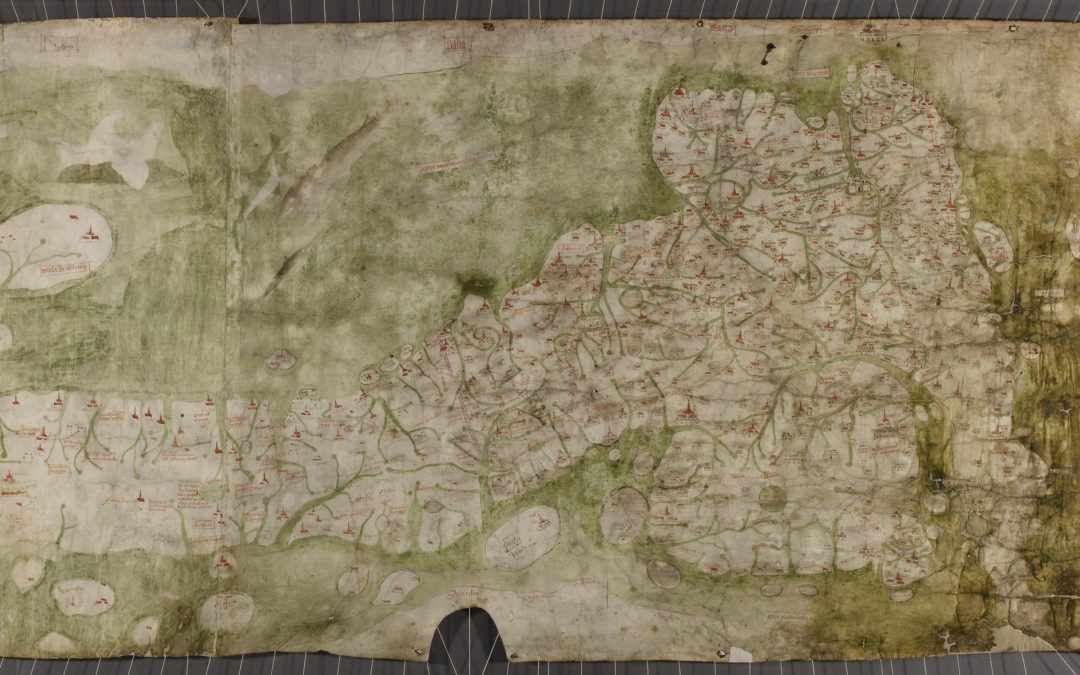

The Gough Map of Britain (presently dated c.1400) occupies a pre-eminent place in the history of cartography, yet remarkably little is known about it. It is much more significant than just being the earliest extant detailed map of the island of England, Scotland and Wales; it is also one of the earliest-surviving examples in Europe of a new type of cartographical genre: the large separate-sheet regional map.

The Gough Map’s many outstanding questions

The map remained in obscurity until 1774, when the antiquary Richard Gough purchased the badly worn and damaged parchment from a private library. In 1780 he published a reduced copperplate facsimile (Plate VII in Gough’s British Topography), further damaging the map in his attempts to decipher it. Subsequent efforts to identify places named and depicted on the map—and to discover when, why, how, by whom it was made—have proved inconclusive.

Modern publications on the map have continued to rely heavily on E.J.S. Parsons’ essay—The Map of Great Britain … an introduction to the facsimile (1958)—despite its often dubious transcriptions and identifications. Certainly the gist of recent publications suggests that a completely new approach to the document is overdue.

Our project—‘Understanding the medieval Gough Map through physics, chemistry and history’—will offer this reconsideration. As a comprehensive, interdisciplinary and collaborative survey, this investigation is distinctive for starting with a close study of the artefact itself rather than with the secondary sources that describe the map.

Understanding the Gough Map: three phases of scientific and historical research

Our new project has three distinct research steps which bring together the specialisms of physicists, chemists, digital humanities researchers and historians.

Phase One …

will analyse the materiality and physical composition of the Gough Map. This will include the application of hyperspectral imagery, Raman pigment analysis and 3D scanning to identify classes of pigments and the sequence of their application.

“It’s hoped the Gough Map project will promote the creation of a single database of pigment analyses, facilitating cross-reference in future research on English manuscripts.”

The scientific component of the project will be led by David Messinger (Director, Digital Imaging Laboratory, Rochester Institute of Technology, USA) together with David Howell (Head of Heritage Science, Bodleian Libraries), who will undertake hyperspectral analyses; Andrew Beeby of the Department of Chemistry, Durham University, who will oversee the (Ramon pigment analysis; and Adam Lowe (Factum Arte, Madrid) who will direct the 3D scanning and image creation.

All welcome this opportunity for cross-disciplinary collaboration, recognising the need for close dialogue between scientists and historians if the latter’s questions about the map are to be resolved. It’s hoped that the Gough Map project will in turn promote the creation of a single database of pigment analyses, facilitating cross-reference in future research on English manuscripts.

Phase Two …

will focus on the processes of the map’s compilation—its marking, drawing, colouring, inking and inscribing—especially as recovered through the initial scientific analyses.

Our trial investigation (published in the journal Imago Mundi, 69:1, 2017) revealed that the Gough Map that has come down to us was not a single compilation by a particular ‘map-maker’, still less made for presentation. Rather, it was the outcome of three main map-making episodes:

- the first (Layer 1, incomplete) shows the whole of Britain from Scotland to the English Channel;

- a second (Layer 2) is a reworking of that map south of the Pict’s [Hadrian’s] Wall;

- the third (Layer 3) is a re-inking of place-names in the south-eastern/central quadrant of England

“It is now clear, in short, that the document was created from the start as a working map, to be laid on a table, consulted, and constantly amended.“

It was also discovered that the first map was copied from an older map, about which nothing is known, and that the copying process employed a seemingly unprecedented technique involving the use of pins to prick onto (but not through) the parchment to indicate both the position and the category of the place sign (village, place with tower, place with spire) that was to inscribed.

As current work proceeds, however, the neatness of that initial model is rapidly fragmenting as the coherence of, especially, Layer 2 dissolves into a confusing matrix of piece-meal modifications and additions. It is now clear, in short, that the document was created from the start as a working map, to be laid on a table, consulted, and constantly amended. By and for whom, and for what purpose, remains to be discovered.

Phase Three …

will provide an in-depth analysis of the Gough Map’s topographical content. The map contains some 650 settlements of various types or ranks, all represented pictorially, as well as more than 800 toponyms, 200 natural features (mainly rivers), and a number of mytho-historical inscriptions and drawings.

Given the size of Britain and the amount of information on the map, it is unreasonable to expect a single person to account for the selection and presentation of the content in the required depth of historical scholarship.

Accordingly, the island has been divided into 12 regional units for the purposes of topographical research, and a similar number of themes for the study of specific aspects: coasts, rivers, place signs, myths and legends, distance lines, North Sea decorations, and the antiquary Richard Gough, etc. The toponyms will receive special attention to make them available for the first time to the place-name studies of England, Scotland and Wales.

Outcomes of the Gough Map project

We anticipate two principal outcomes from our research. The first will comprise a permanently-maintained interactive database and a re-vamped website (now hosted by Oxford University) which will contain the best-available high resolution image of the map. The online resource will include a place-name gazetteer which is being compiled from a number of sources.

“A working area on the website will encourage discussion, teaching projects, and further investigation.”

These include not only well-known early (pre-1600) derivatives but also the first printed facsimiles (Richard Gough’s reduced engraving of 1780 and the Ordnance Survey’s experimental photo-zincograph of c.1871; both hitherto unstudied) in the hope of confirming or correcting already-published transcriptions. A ‘working area’ on the website will encourage discussion, teaching projects, and further investigation (for which separate funding will be sought to encourage new research relating to any aspect of the map to ensure continuous use and maintenance of the site).

Our second output will take the form of a multi-authored monograph (edited by Catherine Delano-Smith and Nick Millea) which treats the Gough Map in all its cartographical dimensions—as artefact, image, and repository of information. It will be aimed at the general reader as much as historians of maps.

For the latter the project’s holistic and collaborative approach will provide a methodological exemplar, with the map set into its immediate political context as well as (in a pioneering example of the emerging separate-sheet map genre) into the wider intellectual context of maps and mapping in medieval western Europe.

The challenges posed by the Gough Map entail intensive collaboration. Face-to-face discussions are essential if the technical and the historical components of an interdisciplinary project of this nature and scope are to be fully integrated. But the potential rewards from such a collaborative approach are extensive. Together we seek to shed new light on this remarkable and so far unusual example of an early working map created expressly for consultation.

Dr Catherine Delano-Smith is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Historical Research and an expert in medieval cartography. She has published extensively on the history of cartography over many years and is Editor of Imago Mundi. The International Journal for the History of Cartography. Her collaborative Gough Map project received funding from the Leverhulme Trust in March 2019.