By Catherine Clarke and Matt Shaw

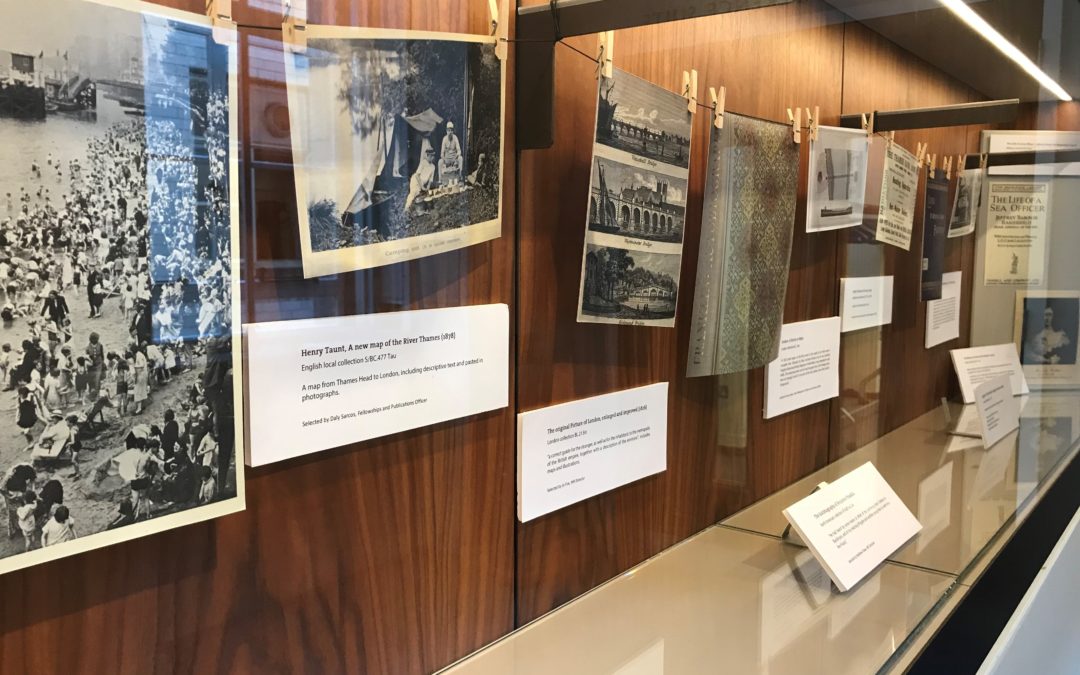

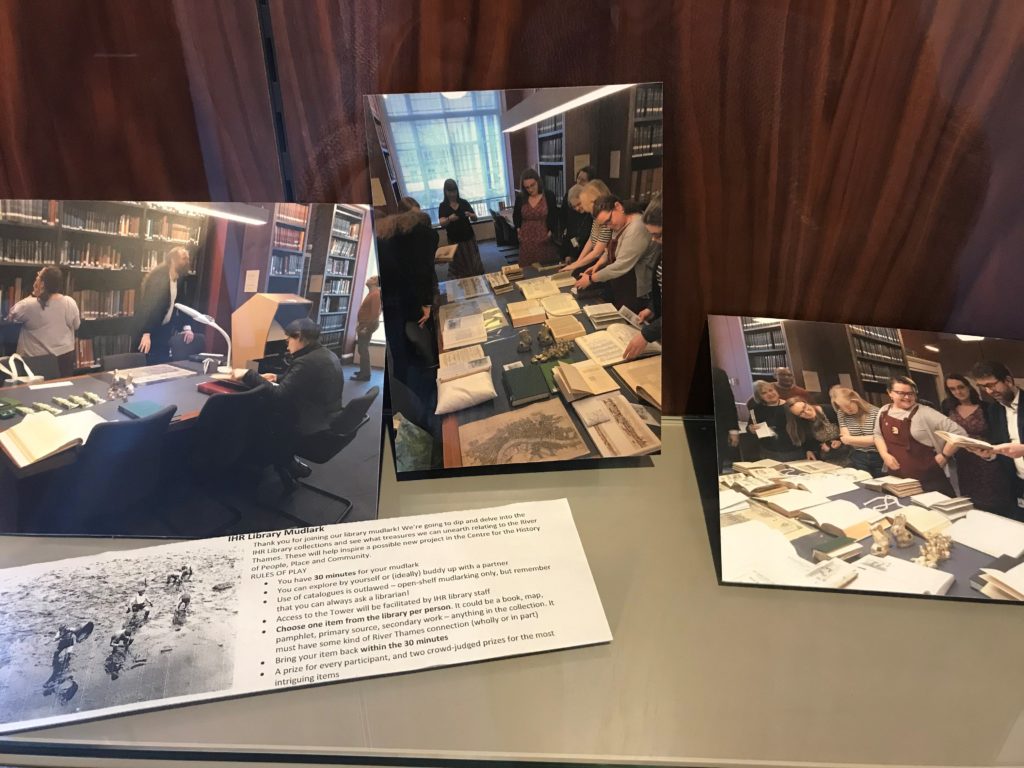

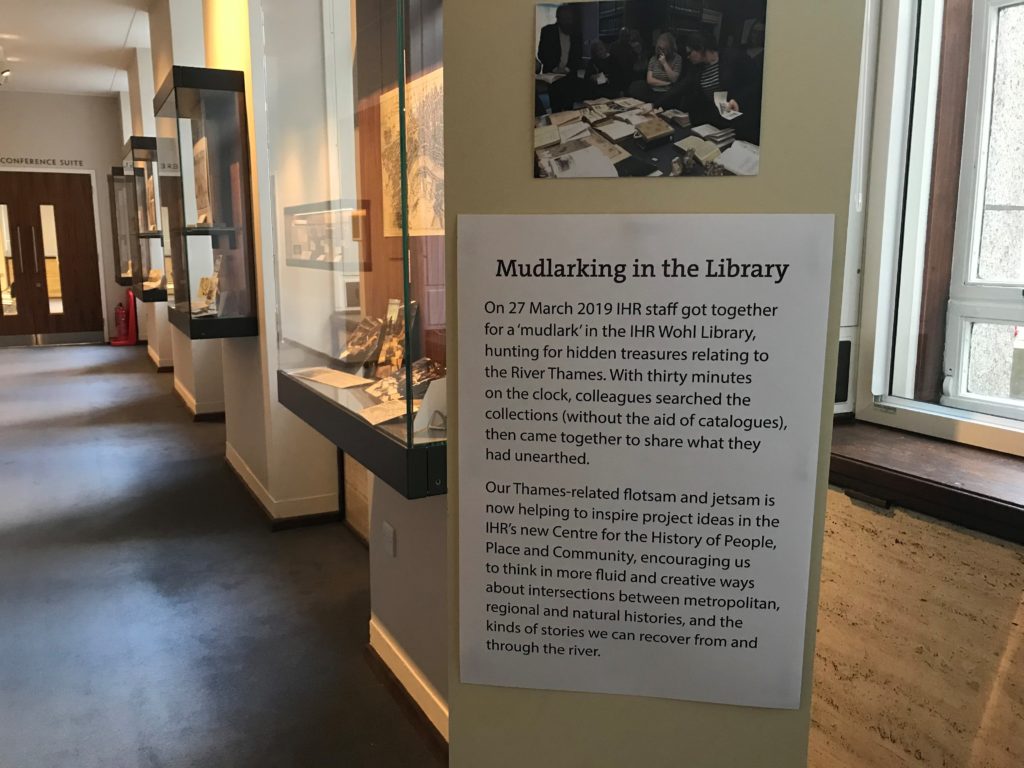

IHR staff recently embarked on a ‘mudlark’ in the IHR Wohl Library, hunting for hidden treasures relating to the River Thames. With thirty minutes on the clock, colleagues searched the collections (without the aid of catalogues), then came together to share what they had unearthed. This Thames-related flotsam and jetsam is now on display in an exhibition at the IHR (May-October 2019) and is helping to inspire project ideas in the IHR’s new Centre for the History of People, Place and Community. How has the IHR mudlark helped us to think in new ways about the Thames and historiographical approaches to the river? What kinds of unexpected sources did this experiment uncover? And what happens when researchers get ‘muddy’?

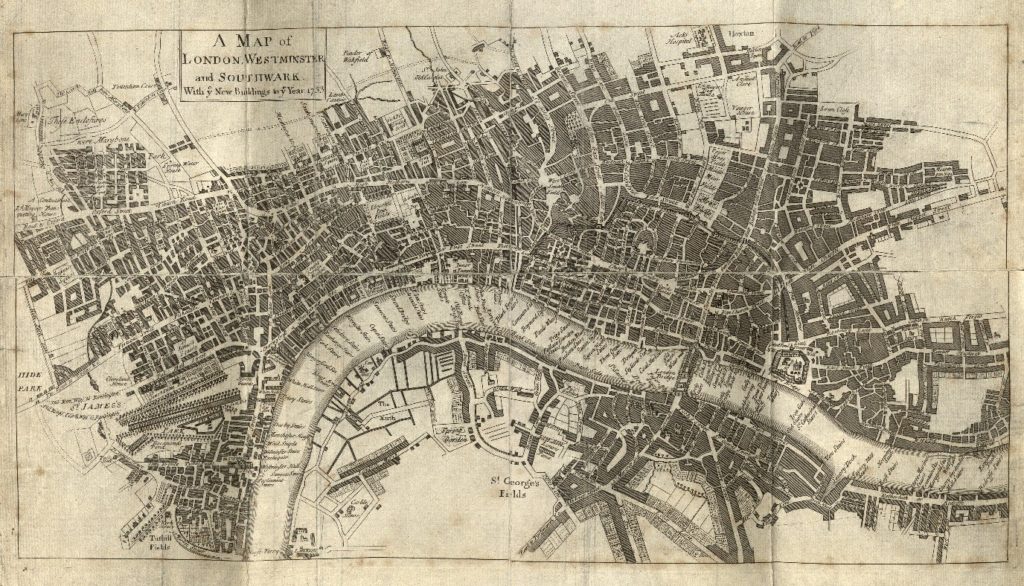

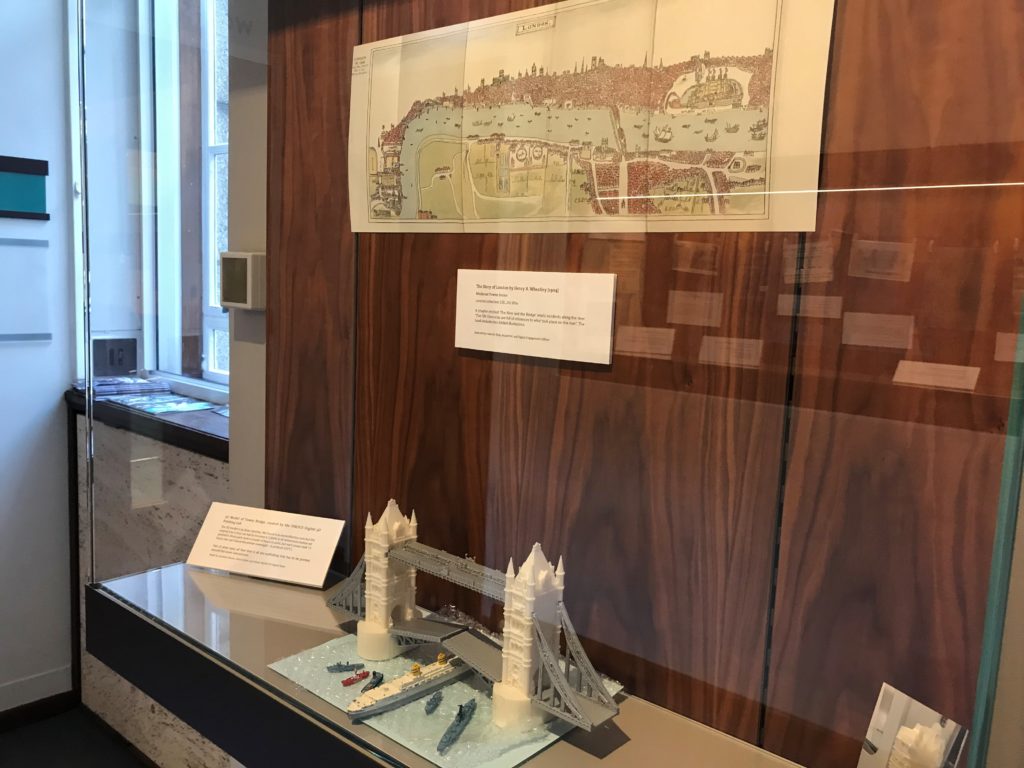

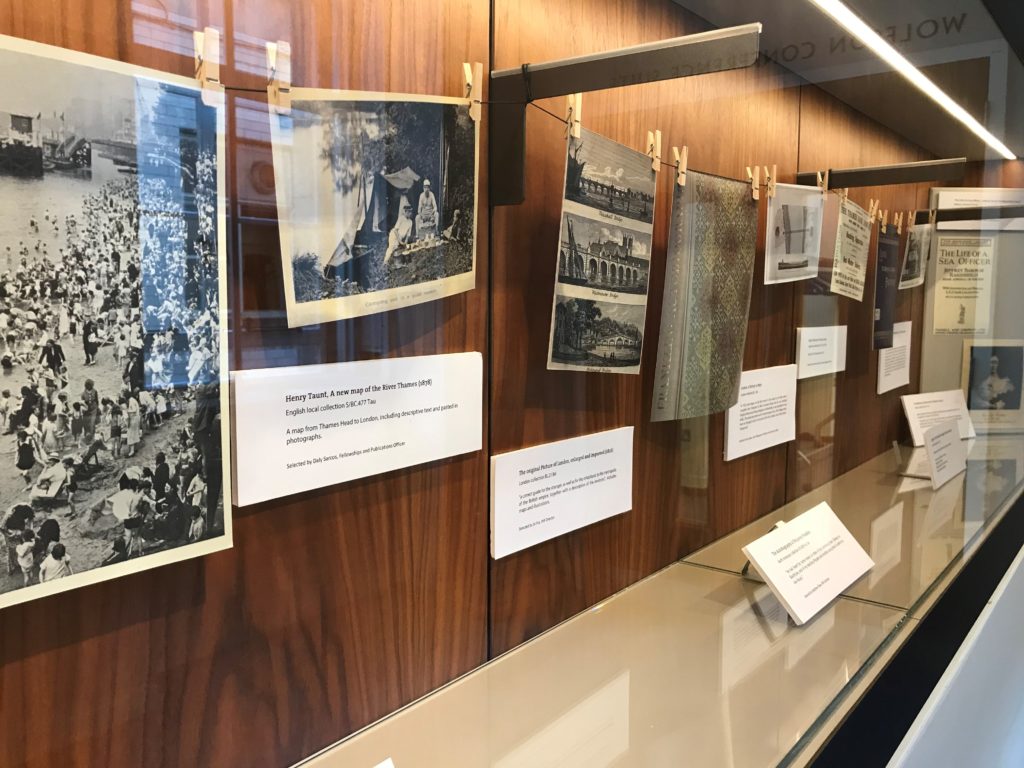

When we gathered our findings, we were struck by the range of items that we had dislodged from the library stacks. Maps featured strongly, from a giant Victorian analysis of the geography underpinning the Thames’s snaking through London (R.W. Mylne, Map of the Geology and Contours of London and its Environs (1856) M/Eng/Lon/1856) to a more bucolic rendering of its course in Thombleson’s Thames (1834) (S/BC.477 Fea). Other maps detailed the close links between the river and the city, with a Map of London, Westminster and Southwark (1733) carefully noting the ‘stairs, wharfs, docks, ferries, keys [sic]’ and the solitary ‘bridge; Bank Side’ is boldly marked as its own domain (S/BL.1/1733). Other findings were more textual, from Benjamin Franklin’s boastful accounts of his swimming exploits in during his first London sojourn (‘He had heard by some means or other of my Swimming from Chelsey to Blackfryars, and of my teaching Wygate and another young Man to swim in a few Hours’, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, UF.428 Fra/Lab) to the history of swans and swan-keeping, recalled in N. F. Ticehurst, The Mute Swan in England (1957) (B.159 Tic). Some colleagues were drawn to the excitement of capsized early-modern Londoners in the facsimile view of London Bridge, replete with rows of heads on spikes and first engraved in 1597. (M/Eng/Lon/Bri/1597).

More congenial, perhaps, was the personal account of three Edwardian proto-hipsters in a boat, lovingly preserved with photographic prints in H. Taunt, A New Map of the River Thames (1878) (S/BC.477 Tau). Elsewhere, the serious business of the river was captured: trade, waste, regulations, crime, industrialisation. Meanwhile, librarians were happy to see the discarding of shop-worn clichés of things lost among ‘dusty’ shelves, and wondered instead about the suitability of grasping treasures uncovered by the churn of regular use, the stacks as jetties, moorings, and working wharfs, with readers following whatever caught their eye among a landscape whose naturalness hid a carefully formed series of underlying structures. Just as the mud slopes of Bank Side offered a space for labour and production, so the careful classification of subjects, juxtaposition of texts allows for a place for creation and discovery.

For the display itself, the library team continued the spirit of play through a collaboration with IHR Digital’s 3D research group. In a very modern take on model making, the team upscaled a digital 3D model of Tower Bridge (created by Brian Sanchez) by 2,000 percent before making use of the group’s 3D printer to produce a miniature replica in plastic of the Victorian gothic simulacra for one of the cases. Toy boats from the 1950s sail under its arches on a convincing sea of bubble wrap. This was one activity that could not be constrained by the formal rules of mudlarking: rather than 30 minutes, each bridge tower took 12 hours to ‘print’.

So what does it mean for researchers to get ‘muddy’, and what might the model of a mudlark afford which a straightforward search of the library collections could not? In the first instance, the parameters of the IHR library mudlark – the timed ‘treasure hunt’ for hidden gems, the ban on use of catalogues and thus on conventional academic research methods – presented the endeavour firmly within the realm of play and playfulness, as a gamified version of scholarly practice. The metaphor of the mudlark derived most obviously from our theme: investigating the history of the Thames. But it also shaped associations and expectations, suggesting a mood of adventure, the potential for accidental encounters and unforeseen discoveries and, once again, a sense of playfulness. The concept of mudlarking also gave us permission to explore the collections in terms of fragments and pieces; not necessarily considering sources in their full context (as would usually be best scholarly practice), but beginning with the partial and the provisional as a starting-point for imaginative engagement, reflection and, potentially, further research in future.

In recent scholarship, mud has proved a suggestive element for thinking through processes of creativity and invention – including in the specific context of academic research. David Trotter’s influential book Cooking with Mud: The Idea of Mess in Nineteenth-Century Art and Fiction (Cambridge, 2000) explores the fertile imbrications between mud and imagination, arguing that mess and dirt are distinctive conditions for creativity in modernity. The book opens with the story of the future novelist, Mary Butts, falling into a muddy puddle, using mud as a starting-point for thinking about mess and dirt more generally, in creative endeavours and in fiction. Trotter explores the role played by mess (and, more specifically, mud) in what he calls ‘the dialectic of illusion or disillusionment’ (p. 5) or ‘the balance between illusion and disillusionment’ (p. 6). For Trotter, mess – mud – is ‘an enabling condition of fantasy’ (p. 7), as well as strongly associated with those generative contexts of chance, accident, possibility and potential. In our imaginary today, we could argue, mud facilitates discovery, adventure and play. Real, messy, oozy river mud translates found objects into a space of fertile uncertainty and ambiguity; it allows transformative imaginative, creative engagements with sources. Metaphorically, the muddy, partial fragments of our IHR mudlark formed suggestive, intriguing starting-points for future work.

But what about a bunch of academic historians, mudlarking in the IHR library? What has mud got to do with scholarly practice and the processes of research? In her essay ‘Muddy Thinking’, in the volume Elemental Ecocriticism: Thinking with Earth, Air, Water, and Fire (ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen and Lowell Duckert, Minneapolis, 2015), Sharon O’Dair explores the darker uses of ‘mud’ in discourses around research and intellectual endeavour. She mobilises a vast range of literary references to mud into a eco-critical analysis of modern academic practices and the idioms associated with them, from accusations of ‘muddy thinking’, to scholarly ‘mud-slinging’. ‘Being bogged (down) in the academy’, she warns us, ‘is today constitutive, structurally, of professional identity’ (p. 148). Yet O’Dair concludes by imagining a different kind of university, ‘where we celebrate mud’s and muddy thinking’s miraculous fecundity, its spontaneous generativity, which allows intellectuality to ooze, to spread outward in community, in otium, resisting the demand, at least on occasion, to sling upward and to sling upward again, for personal glory or fame’ (p. 154). This kind of messy, shared intellectual endeavour was our aspiration for the mudlark, which was an activity as much about celebrating and fostering our collegial identity and research community here at the IHR as any required research findings.

The IHR mudlark invited us to work (or play) together as colleagues, and to approach a research topic – the history of the River Thames – in an experimental and creative way. It encouraged us to think in more fluid and imaginative ways about intersections between metropolitan, regional and natural histories, the kinds of stories we can recover from and through the river, and the messy, playful and accidental routes we can find into our research.

Catherine Clarke, Professor in the History of People, Place and Community, IHR

Matt Shaw, Librarian, Wohl Library, IHR

The IHR Mudlark exhibition is on display at the Institute of Historical Research on the Lower Ground Floor, Summer 2019.