By Victoria Blud, Diane Heath and Einat Klafter, Editors of the collection ‘Gender in Medieval Spaces, Places and Thresholds’ available open access.

As we were leaving the Cathedral after Evensong on a cold night in January 2017, a blizzard suddenly descended upon Canterbury. Traffic ground to a halt for the roads were icy and little could be seen outside pale pools of lamplight. Wifi and electricity failed just as darkness and snow hid familiar landmarks. Quite suddenly, the city grew eerily, icily devoid of twenty-first century standards of safety and stability and curiously medieval as the familiar townscape was replaced by night and snowstorm. That peculiarly medieval sensory experience of place and space was an uncanny but rather apt beginning to Canterbury Christ Church University’s medieval studies conference, Gender, Places, Spaces and Thresholds, and that feeling of being in and out of place lent an unexpected dimension to the proceedings and the work that came out of it. Working together on the gendered experience of space and place, we encountered gendered journeys and pilgrimages, shifting definitions of public and private space for women and for men, lifecycles that were not only temporal but locational – from the lying-in room to final resting place – and, perhaps most of all, the efforts that go into laying claim to place.

The manuscript image below is taken from another former Canterbury resident: a text that was once property of St Augustine’s Abbey, whose former grounds are now occupied in part by Canterbury Christ Church University. It depicts the Bearded Lady of Limerick, using her drop spindle to spin thread and spin yarns in a copy of Gerald of Wales’s History and Topography of Ireland (Topographia Hiberniae, London BL MS Royal 13 B VIII). Gerald claims that she would travel around with King Duvenald’s court, an object of amazement as well as ridicule, and insists on her difference from another fascinating courtier in Connaught, who is by contrast described as a hermaphrodite. From her seat at the foot of the page, in the margin of a text about the weird and wonderful inhabitants of the outer reaches of the Angevin empire, composed by a brilliant writer who nonetheless saw himself as a marginalised figure through his own Welsh ancestry, the Lady shows what it is to be of a place, at the edge, in the centre, the subject of gendered debate, and the focus of medieval artistic invention.

Studies of space and place enable us to examine how we are defined and confined by location and physical or imaginary presence, and interrogate the thresholds between sacred and secular, public and private, enclosure and exposure, domestic and political, movement and stasis, and masculine and feminine. In the middle ages, as today, where individuals and communities make and are made by the places and spaces they inhabit, gender and space become mutually constructive. Medieval gender studies are well placed to address issues of place, space and threshold since they situate the understanding of such concepts in the context of long histories of exclusion, seclusion, escape, expulsion, and stereotyping. Yet medieval gender issues related to place, space and liminalities are still being addressed and reassessed, despite this field of study having a great deal to offer in terms of the history of cultural practices including literary and artistic creation.

Contemporary theory has long suggested productive directions for research into such sharply gendered medieval institutions such as religious houses or guilds, particularly how the intersection of space and ritual in these institutions formed a significant part of the fabric of local society, how women in particular managed to exploit strategic locational strengths to exert authority, and the roles they were able to play even in institutions such as guilds that did not permit them to hold office.

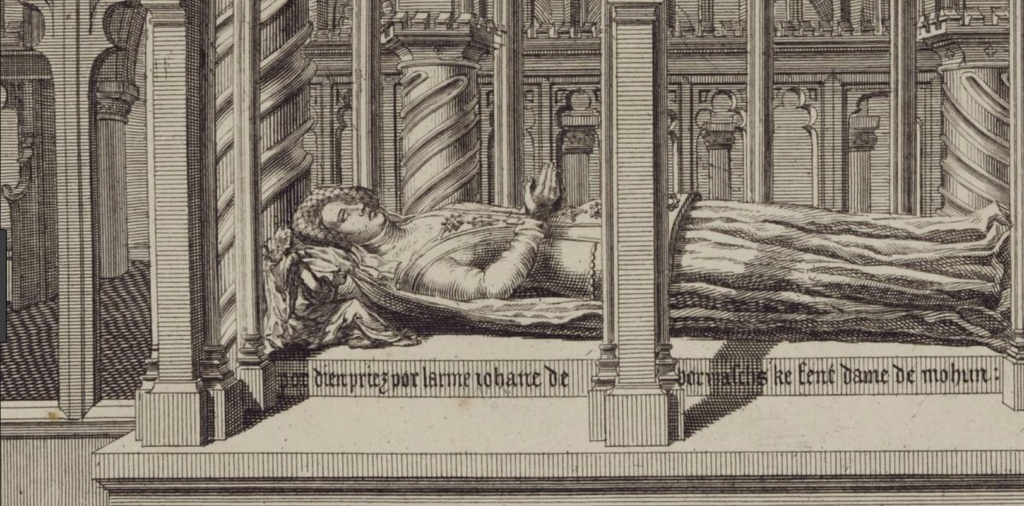

Image crafting was as familiar to a medieval audience as it is to the social media age, and a key factor was the careful and subtle blurring of the public and the private sphere by those with means. Joan Mohun carved out just such a public space for herself through her meticulously planned “tombscape” in Canterbury Cathedral, occupying a highly prestigious space close to St Thomas Becket’s shrine and in the eyeline of the Virgin Mary. Laying claim to space is also a question of visibility: as recent work on medieval murals of women in Kentish cathedrals – rare, but there – reminds us as clearly as the recent run of gender-flipped movies and the spotlight on own-voice narratives, to be represented is to be seen; it is to be present after and without literal presence.

The importance of representation is still a core concern for the Gender and Medieval Studies conferences – representing those on the margins in medieval culture, representing new voices in contemporary research. We so often experience the medieval in specific spaces – the archive, the exhibit, the conference – but scholarship now happens increasingly in new ‘places’: not just in a wider range of social and economic groups, but online and on social media, where virtual delegates engage in conference debates and readerships evolve to be broad and often unexpected. The ways in which spaces and boundaries are defined, and the issue of who is expected or allowed to be in those spaces, and to be kept in or out of them, are too often presented as a matter of fact rather than as a matter of power. The experience and control of spaces and places have far-reaching resonances, as witnessed by the current academic debates ranging from safe spaces to #metoo. As our own project began, medieval gender studies was still dealing with the fallout of the education news cycle that centred on the “femfog” controversy. The global outcry in the academy over extreme misogynist remarks by a leading Anglo-Saxonist ironically highlighted the abuses of privilege, harassment, micro- and macro-aggressions that are still too common and entrenched in university and conference settings. Such issues are only exacerbated by an ever-increasing “threshold” before stable employment that new scholars face in the changing environment of higher education.

Yet the continuing evolution of the spaces and thresholds of disciplines is also a force for intellectual innovation and progress and cause for celebration, especially when the work of emerging scholars can be brought to a wider audience. Two years after that disorienting, snowy day, this collection returned to Canterbury for a launch to coincide with International Women’s Day: embracing new directions as well as new collections, gender and medieval studies are still going places.

Victoria Blud is a research associate at the Centre for Medieval Studies, University of York

Diane Heath is a research fellow in the Centre for Kent History and Heritage at Canterbury Christ Church University.

Einat Klafter is a teaching and research associate at the Zvi Yavetz School of Historical Studies at Tel Aviv University.