By Cristina Sasse

Nowadays, when we are new to a town or need to find information about a doctor or a certain type of shop, we use internet search engines, web mapping services, and mobile navigation apps to find what we want. We use social media, online encyclopaedias, and official webpages to retrieve information on people, places, and institutions. In eighteenth century England, there were various media available to townspeople and travellers which provided this kind of information, ranging from handbills, advertisements, newspapers, and official publications to guidebooks and topographical descriptions. But there was one genre which was specifically designed to encompass all the vital information that might be of interest to anyone visiting or at home in a given town: the so-called ‘directories’.

Town directories – the early modern ancestors, so to speak, of the telephone directory and the Yellow Pages – first made their appearance in London c.1670. From the 1760s onwards, as England experienced increased urbanisation and a growth in inland trade and travel, they became a popular type of publication in many of the larger English towns. Originally, they consisted simply of a list of traders, merchants, and artisans arranged alphabetically alongside their name, profession and address. Soon, however, such lists were supplemented by various kinds of information on transport options, markets, inns, churches and public amenities. Increasingly, histories and descriptions were added as well, so that many directories became a type of guidebook (some examples can be found in Leicester University’s Historical Directories collection). They were intended to help visitors and residents to get in contact with potential business partners and customers, to help them to find the goods and services required and the places where such people could be met and wares be bought and sold. In the words of one editor, directories were ‘depositories of local knowledge’.

Pigot & Deans’ New Directory of Manchester, Salford, &c. for 1821-2

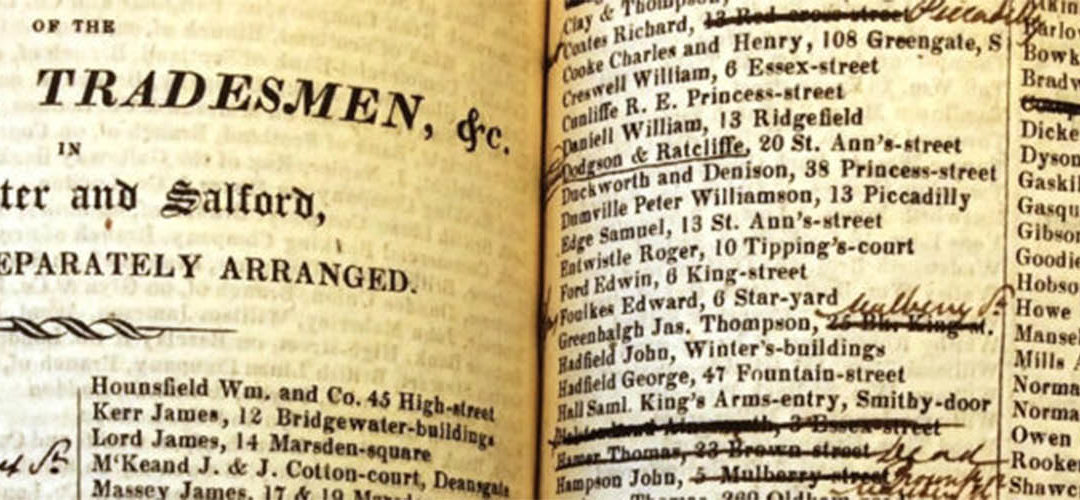

While the growing popularity and increasing number of published directories in the mid-eighteenth century suggests that they were indeed used as depositories of local knowledge, evidence as to how individual readers perceived and employed them is scarce. In some volumes, however, users have left traces in the shape of markings, annotations, notes and comments that help us form an idea of who they were, what was of interest to them and how they applied the information provided. One such volume is the Manchester and Salford Directory for 1821-2, published by Pigot & Dean and held in the IHR Wohl library. The heavy layers of markings and annotations made by its first owner, Charles Wood, are highly uncommon for a surviving directory from that era and they are all the more valuable to historical research since there was virtually no contemporary public discourse on the function and use of directories.

Pigot & Deans’ New Directory of Manchester, Salford, &c. for 1821-2. IHR library’s annotated copy.

Wood evidently bought the book soon after it was first published. He recorded the date together with his name on the title page. His own entry within the directory tells us that he was a solicitor in Manchester. Throughout the volume, which includes several lists of people in the professions and in trade as well as information on town officials, public institutions and transport on more than 300 pages, Wood has added missing information, updated or corrected individual entries and crossed out others by hand. He particularly took note of removals, deaths and business failures, marking the respective entries by the words ‘dead’ or ‘failed’ or by substituting the new address. As a solicitor, he seems to have paid special attention to those in the legal profession, his colleagues and competitors. This is most evident in that section of the directory which is organised by trade: the greatest proportion of Wood’s markings and notes can be found on those pages listing the lawyers of Manchester. Similarly, most of his corrections and additions relate to entries of persons with addresses in the vicinity of his home. Wood lived in Brazennose-street, about a quarter of a mile from the Exchange, and the majority of alterations he has undertaken concern someone with a residence, office or workshop close by or in the town centre.

From these annotations and additions, we can get an idea of which people and places were of interest to him, and across which spaces he moved in the town and along which routes. His many notes and markings give us an insight into how he stored, organised and retrieved the information necessary for and gained through his daily life in Manchester. Wood acquired a directory and evidently used it as a resource for cultivating relationships and networks to find his way around the expanding and ever changing town and keep track of the world around him. That he did so frequently is demonstrated by the fact that he updated the printed information with great care and diligence. The main problem of directory compilation was that it took several months to collect and arrange the material, so that by the time a book was published some of the information was already outdated. Wood seems to have understood that the directory would only serve the purposes for which he intended to use it if he updated its content himself. The way that he has made additions and corrections shows he took seriously the order in which the information was presented. Wherever possible, he has placed additions in their correct spot within the alphabetical order of a list and written corrections immediately before or behind the affected entry instead of drawing up a separate list of alterations. He obviously wanted the newer information to stand in the place of the old, because this was where he was most likely to look for it and where he needed to find it quickly. The traces he has left in the volume let him appear as someone who was aware that certain media and techniques were necessary to handle successfully the enormous amount of information involved in a professional life in one of England’s largest towns at the beginning of the 19th century. However, the directory provided for him only the basic content and frame to which he contributed his own knowledge, creating a highly individual and specific store of local information.

While the number of handwritten annotations may be exceptional in this volume, many other owners and readers may have used their directories in a similar fashion. What is truly unusual is that a book with such heavy traces of usage has survived at all since many directories were simply discarded once they had gone out of date and a new edition was available. The ones that were preserved have mainly been employed by historians as data pools for the statistical analysis of the social and economic structure of towns. However, this was not what they were originally compiled for, nor is it how most contemporaries used them. They were designed as complex and manifold information depositories, arranged so that pieces of information could be easily retrieved. As the example of the volume from Manchester shows, directories can be valuable sources for exploring how eighteenth and early nineteenth century townspeople collected, stored, organised, retrieved, and applied information about the spaces and communities within which they lived. This allows us new insights into the history of knowledge as well as urban life and culture in a time of rapid urbanisation.

Cristina Sasse is a Research and Teaching Assistant at the department of Early Modern History at Justus-Liebig-Universität Giessen, Germany. In her doctoral dissertation she is studying the role of English town directories between 1760 and 1830 in constructing urban spaces and improving orientation and communication within towns.

Cristina Sasse is a Research and Teaching Assistant at the department of Early Modern History at Justus-Liebig-Universität Giessen, Germany. In her doctoral dissertation she is studying the role of English town directories between 1760 and 1830 in constructing urban spaces and improving orientation and communication within towns.