By Francis Calvert Boorman

London has long been thought of as the archetypal conurbation; a vast and unbroken metropolis nevertheless made up of distinctive localities. As the writer and politician Joseph Addison (1672-1719) mused in The Spectator in 1712, ‘When I consider this great city in its several quarters and divisions, I look upon it as an aggregate of various nations distinguished from each other by their respective customs, manners and interests’. More than one historian has been drawn to the metaphor of a ‘patchwork’. Yet there is still a dearth of scholarship that focuses in on particular areas in London, describing those curious customs and crucially advancing our understanding of the complicated local government of the capital.

A new book from The Victoria County History on the Westminster parish of St Clement Danes from 1660 to 1900 has just been published. It shows how the local approach to London is developing our understanding of the capital’s past. The book situates the parish in a fast-expanding metropolis that, in Addison’s time, soon petered out into fields to the north. By 1900, however, it had developed sprawling suburbs, and St Clement Danes was at the heart of the Empire’s capital.

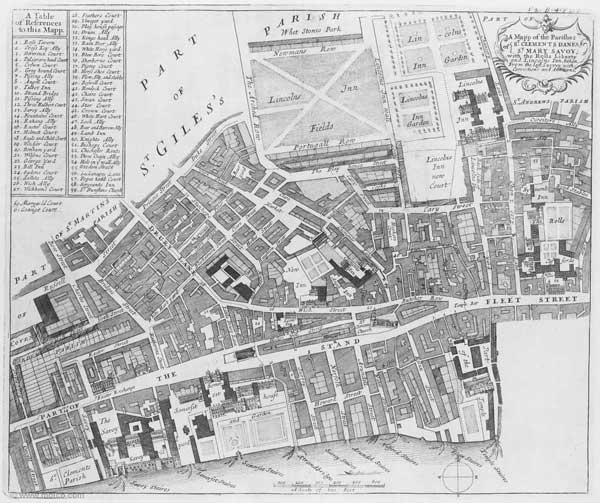

Map of St Clement Danes from J. Strype, A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster (1720)

St Clement Danes church sits on an island in the middle of the Strand and is now the central church of the Royal Air Force. The medieval church survived the Great First of London but was rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren in 1682, and today little else in the parish survives from the seventeenth century. The book charts the transformation in the physical environment of the parish, as well as its changing institutions and economy.

At the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, a string of grand aristocratic houses lay along the north bank of the River Thames. To the north of the Strand were several Inns of Chancery, where many lawyers had their chambers. Stretching up to Lincoln’s Inn Fields was an area of housing and the newly-built Clare Market, where meat, fish and other food was sold. Theatres returned to the parish after they were suppressed under Cromwell, with indoor tennis courts used to stage plays until purpose-built spaces were constructed.

As the aristocracy moved to new developments further west, the big riverside mansions were built over by developers who realised the greater profits to be made from streets of townhouses. By the mid eighteenth century the parish was dominated by respectable middling sorts, independent artisans, shopkeepers and lawyers. These men ran the vestry, the local government which policed and maintained the streets and provided for the poor, alongside the parochial charities.

The same group of male tax-paying homeowners had the right to vote for the two Westminster MPs. It was a restricted franchise by modern standards, but quite broad compared to many other constituencies at the time. The St Clement Danes electorate was fiercely independent, campaigning vigorously against government candidates and embracing radicals like Charles James Fox. Although excluded from voting, other parishioners participated in politics through demonstrations and social movements. For instance, in 1749 a bawdy house riot broke out at a brothel called the Star on the Strand and spread across London. The Clare Market butchers were a prominent feature in the street life of the parish, as was the noise of their famed marrow-bone-and-cleaver music.

As the nineteenth century wore on, slums developed around Clare Market and the quality of produce fell away. Following a police raid on a molly house (a gay meeting place) and the growth of pornographic book trade in Holywell Street, the parish gained a seedy reputation. The vestry lost many of its powers to London-wide bodies like the Metropolitan Police and the Metropolitan Board of Works. Spectacular additions to the built environment included the Victoria Embankment and the Royal Courts of Justice, but slum clearance only concentrated the poor in the remaining housing and exacerbated overcrowding. Charitable provision of local schools, a church mission and medical treatments were not enough to alleviate conditions which the reformer Charles Booth felt were ‘too disgusting for words’.

Royal Courts of Justice, in the parish of St Clement Danes 2017 © University of London

The remaining slums (and medieval buildings) were swept away in the development of Aldwych and Kingsway beginning in the 1890s, that laid out the street pattern we still see today. The local community was dismantled: most of the replacement housing was situated outside the parish and the vestry was superseded by the London County Council in 1900.

This story, told in greater detail in the book, shows the value of the microscopic approach to London history. There is so much more to discover in the localities of London. It was Samuel Johnson, that famous parishioner of St Clement Danes who declared, ‘If a man is tired of London, he is tired of life’.

This book is the second in the Victoria County History Shorts series for the City of Westminster and the historic county of Middlesex. The first, Knightsbridge and Hyde, was published in 2017 and a third, on the parish of St George, Hanover Square, from 1725 to 1900 funded by the Grosvenor Estate will follow. This work will ultimately contribute to the thirteenth of the Victoria County History’s ‘red books’ on the county of Middlesex. Those published to date are available for free via the Institute of Historical Research’s digital library, British History Online. The Victoria County History Shorts series also includes titles from Hampshire to Cumberland. They are available in print and as e-books from the School of Advanced Studies online shop.

Follow the Victoria County History on Twitter, or visit the website.

Dr Francis Calvert Boorman is an Associate Research Fellow at the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies. He has edited the newly-published book, from the Victoria County History, St Clement Danes, 1660-1900.