By Matthew Shaw

There have been numerous acts of commemoration for the centenary of the First World War. Many of these have undoubtedly chimed in meaningful ways with the public’s imagination or emotion, such as Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red at the Tower of London, or Rufus Norris and Jeremy Deller’s collaboration we’re here because we’re here. More broadly, the centennary has been well-served, at least in number and often in artistic or academic quality, by television documentaries, radio dramas, films, song cycles, plays, books, graphic novels and comic books, serial tweets, digitisation, cataloguing and crowd-sourcing projects, and, of course, academic conferences and writing. Within such commemorative, artistic and intellectual endeavours – much of it funded, supported, and to some extent directed by official bodies such as the Heritage Lottery Fund and UK government departments – emphasis has rightly been placed on engagement with communities here in the United Kingdom. A series of ‘hubs’, for example, has been established across the UK by the Arts & Humanities Research Council as World War One Engagement Centres, which seek to bring together the fruits of academic research and and community participation. Importantly, local people have often led in commemorative work, rather than having commemoration ‘done’ to them.

Given all this high profile activity, which has continued for four years or even longer, it might be assumed that all the bases have largely been covered. It is true that many aspects of the war have been studied, researched and collectively remembered, and newer aspects foregrounded, such as its global context and the consequences for, and contribution by, colonized peoples. But of course, there still remain great areas awaiting study – and groups whose experiences have not received appropriate public commemoration or wider reflection. The experience of mothers who lost loved ones during the conflict is one such aspect.

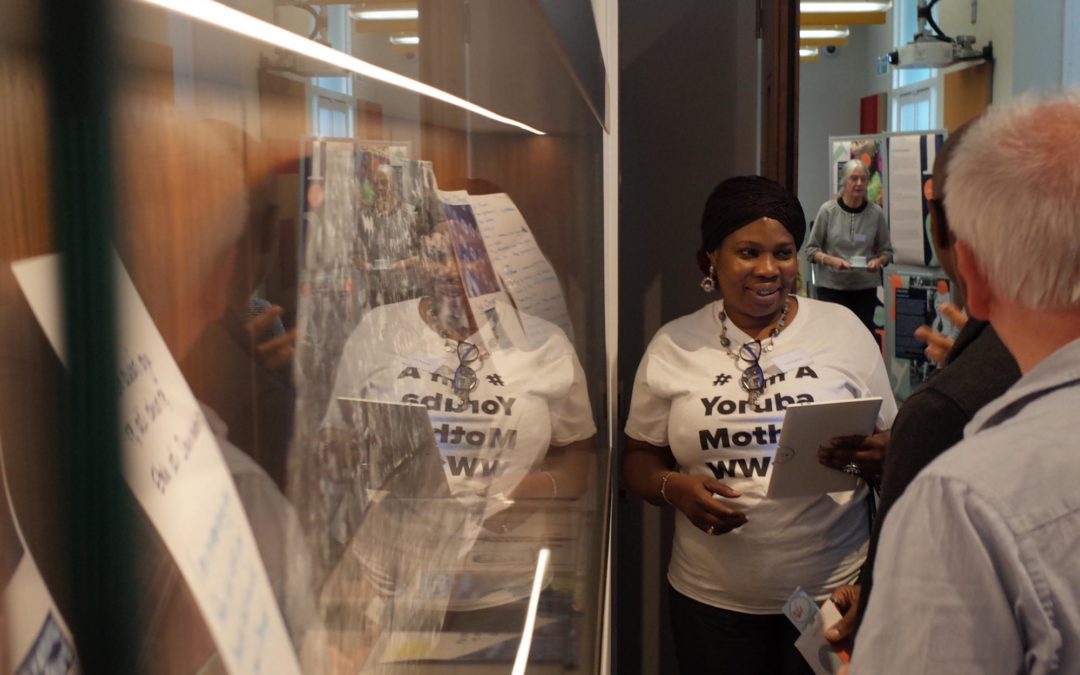

Delegates talk in front of a display case showcasing community group contributions to the Motherhood, Loss and the First World War project (Photo: Matt Shaw)

Following from this, the Institute of Historical Research has been very pleased to be able to work with Big Ideas on their project Motherhood, Loss and the First World War, in collaboration with the London Centre for Public History and Heritage. Launched in March on BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour (to coincide with Mothering Sunday), and funded by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, the Big Ideas brought its expertise in working with local groups to explore the past in innovative and artistic ways, with the aim of developing skills in marginalized communities. Using a resource pack developed by Big Ideas, several groups across the country reflected on known and unknown stories of motherhood and loss, and the communities’ relationship to the experience of the war. Developing skills, such as in presentation or teamwork, the groups produced a range of artistic commemorations, ranging from forget-me-not needlework pincushions (shown below) and letters composed by Yoruba mothers to their sons. Several collections of correspondence between mothers and sons were discovered, and which were used to spark creative writing responses, some of which were read at the project’s conference which took place at Senate House and the Institute of Historical Research on 5–6 Sep 2018. It was an important event for the participants, offering a chance to meet other groups and share experiences, while for the Institute it was an important opportunity to develop our role working with others to explore and support the intersections between history and wider culture and society.

Forget-me-not cushions created as part of the Motherhood, Loss and the First World War project

While the project continues, the conference and series of events offered the opportunity for academics and the community groups to meet and share their experiences, questions raised and knowledge gained (a form of public history that has in part been recorded in this blog post). The first evening concluded with a free public lecture by the US historian, Prof. Susan R. Grayzel on ‘National Service, Personal Sacrifice: The Cultural Politics of Mourning Mothers during and after the First World War’, and the second day finished with a specially-commissioned series of compositions by Clare Connors for violin, based on the letters from Wilfred Owen to his mother, Susan, a women often mentioned in discussions of the poet, but rarely given her own voice. Her letter reflecting on the death of her son, and the publication of his poetry, concluded a moving series of readings and performance in Senate House’s Chancellors Hall.

Motherhood, Loss and the First World War: Evening Musical Performance

Clare Connors is an award winning British composer living in London, who has collaborated with a range of artists, including David Byrne, Kraftwerk, and Spiritualized, and wrote, played and produced for the Balanescu Quartet from 1991 to 2001. She began the process of responded to the Owen letters by writing an imagined letter to her son, and then followed Owen’s letter with a series of at first playful responses to the treats that might come with letters (such a Pep-o-mints), before developing into a series of darker and more harrowing compositions, capturing the themes of hope, fear, absence and longing encapsulated in the connection soon to be broken between mother and son.

With thanks to Virginia Crompton and Sarah Giles (Big Ideas), Edward Madigan (London Centre for Public History), Prof. Susan Grayzel, Clare Connors, Justina Kehinde, and all the speakers and participants in the conference.

Matthew Shaw is the IHR Librarian. He tweets at @_MattShaw.

Matthew Shaw is the IHR Librarian. He tweets at @_MattShaw.