‘Ladies of Quality and Distinction’, a new exhibition at London’s Foundling Museum, traces the history of women’s involvement in the creation and running of the Foundling Hospital—from the twenty-one mid-eighteenth century ‘Ladies’, who signed Thomas Coram’s petition to George II calling for a Hospital, to the governesses and cooks who served the institution into the twentieth century.

Here Janette Bright, an exhibition researcher and PhD student at the IHR, introduces a selection of women who’ve shaped the history of the Foundling Hospital.

On 9 March 1729, Charlotte Finch (1711?-1773) signed a petition supporting the establishment of London’s first Foundling Hospital. As duchess of Somerset, Charlotte lived in the palatial mansion of Petworth in Sussex. Her life was very different to those of the charity she chose to support. However, signing the petition may have been one of the few things she did choose to do. Married to the duke, Charles Seymour, in 1725, hers was a match probably arranged because of her status and wealth.

With her first child less than a year old, Charlotte may have signed because of an empathy felt for mothers who lacked her material comforts. Perhaps she just wanted to make a decision of her own.

Importantly, her action encouraged others. Within four months, fifteen more ladies had confirmed their support to Thomas Coram (c.1668-1751), the founder of the foundling hospital. It took another five years to collect a further six women’s names. The slowness of the process was an indication of the controversial nature of the charity. Many believed it would encourage the poor to abandon their offspring, expecting others to clothe, house and feed them.

Charlotte, Duchess of Somerset, attrib. Charles Agar, courtesy of Lord Egremont

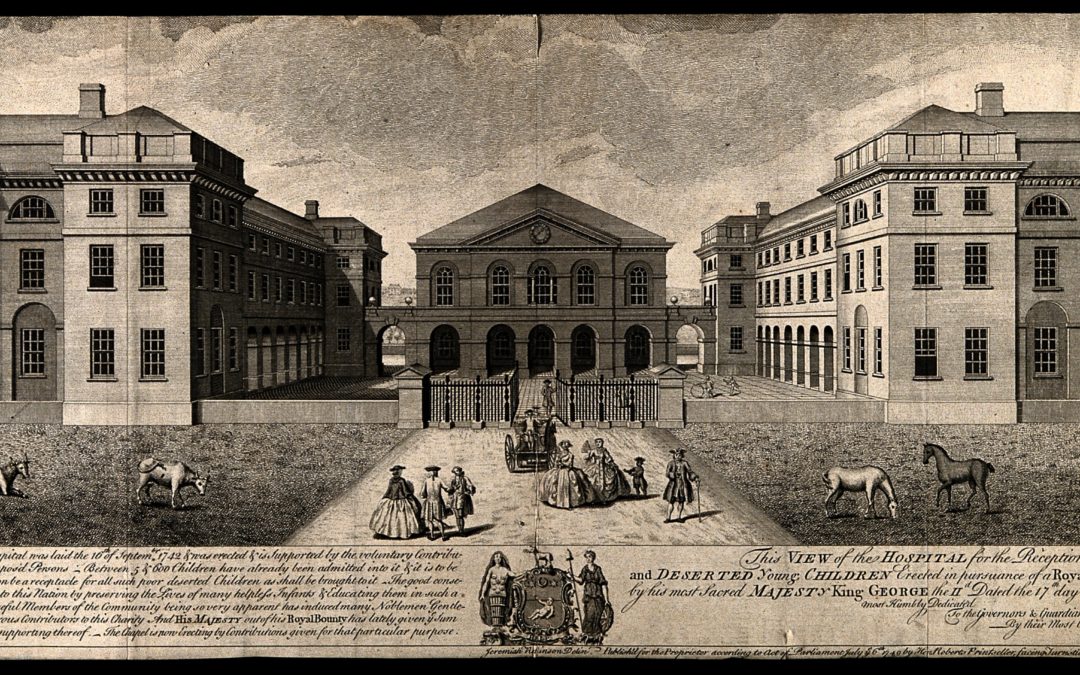

Despite opposition, these women thought differently. Eventually they persuaded their husbands and other influential men, including George II, to agree. Coram’s Foundling Hospital opened its doors on 25 March 1741. Thirty infants were admitted to temporary accommodation in a house in Hatton Garden. Almost immediately plans were drawn up to create a permanent home.

Attention also turned to transforming what the Hospital governors believed to be unwanted infants into useful citizens. Between the 1740s and 1926 the hospital’s staff sought to fulfil this aim in their specially built premises, located close to what’s now Coram’s Fields in central London. In 1926 the hospital relocated to a new site in Hertfordshire and since 1954 the establishment has continued as a children’s charity and a museum, now located close to the original site.

For the centenary of the 1918 Representation of the People Act, curators at the modern-day Foundling Museum decided to reflect on and raise the profile of these pioneering women. The result forms the central part of the museum’s latest exhibition, Ladies of Quality and Distinction which opened to the public on 21 September.

The museum’s first hurdle was to raise funds to begin the process of tracking down portraits of the twenty-one original ladies of ‘quality and distinction’. Finding portraits of all the women was a mammoth undertaking, but the museum’s picture gallery is now beautifully rehung with likenesses of each of the petition signatories between 1729 and 1735. Museum staff have spent several weeks taking down portraits of the male governors which usually line the gallery’s walls, and replacing them with the gathered images of our remarkable pioneering ladies. The twenty-one women’s portraits now hang alongside William Hogarth’s portrait of Thomas Coram, the image of the man they supported almost three hundred years ago. Those now featured – and who signed the original petition include, in addition to Charlotte Finch – Isabella Montagu, duchess of Manchester, Henrietta Needham, dowager duchess of Bolton, and Margaret Cavendish Harley, duchess of Portland, who was the final signatory in May 1735.

Ladies of Quality and Distinction, Foundling Museum, 2018 (c) Peter Mallet Photography

Building a home for the first children was a major challenge but looking after them was quite another. This is where another group of women was required, including matrons, laundry maids, cooks, nurses and schoolmistresses. There were also male staff in the eighteenth-century hospital. However, they were in the minority and it was hospital’s female staff who dealt with the day-to-day problems of caring for babies, children and later some adults.

During the four years known as ‘General Reception’ when the Hospital operated an open-door policy (1756-1760), dozens of infants arrived each day. It was the Hospital nurses who were required to deal with these babies. Many of the children were sickly; some died in their nurses’ arms. Those who survived needed feeding, clothing and educating.

Most of the staff lived at the Foundling Hospital and cared for the children from dawn to dusk. Despite long hours, many women must have been attracted by the opportunity of work that also included bed and board. Some of these women began as foundlings themselves. Esther Yardgrove (1741-1809) arrived as a seven-week-old baby and worked her way up from laundry maid to school mistress. She died at the Hospital aged 68.

Not all of the Hospital’s staff and supporters were based in London. For their first five years or so, children were cared for in premises across the country. These nurses collected infants to be fostered in their own homes. Inspectors were given the task of recruiting nurses, paying their wages and ensuring the women looked after the children properly. The majority of inspectors were men, though there were also many women. Although this role was unpaid, the Hospital was unique in recognising its women inspectors as being on equal terms with the men.

Nurse and children at Foundling Hospital summer camp, c.1910-20, courtesy Coram

The Foundling Museum’s Ladies of Quality and Distinction exhibition looks not just at the twenty-one society women who gave valuable support to Thomas Coram in the 1730s. Equal attention is given to the many unsung female staff workers who served the Hospital over three centuries: from eighteenth-century scullery maids to twentieth-century governors. Brought together by a single institution, it shows what remarkable women they were.

Ladies of Quality and Distinction runs at the Foundling Museum, London, until 20 January 2019. Further details of opening times and a programme of accompanying events, including concerts, talks and family activities are also available via the Museum’s website.

Janette Bright is a researcher and guide at the Foundling Museum, London, and is currently writing a PhD on the eighteenth-century Foundling Hospital at the Institute of Historical Research, University of London. Her publications include (with Gillian Clark) An Introduction to the Tokens at the Foundling Museum (2011).